2022 has seen no shortage of great performances so far, from Cate Blanchett to the erstwhile Short Round. But two of the most unexpectedly delightful star turns come from a pair of computer-generated robots. Those would be NASA’s Spirit and Opportunity Mars rovers, brought back to life through stunning computer imagery in Ryan White’s lovely new documentary Good Night Oppy. In addition to the animated “reenactments,” White uses archival footage and interviews with NASA scientists and engineers to tell the story of the exploratory robots, both of which outlived their anticipated 90-day lifespan by several years (Opportunity remained active from 2003 to 2018!). On the eve of the film’s local debut at the GlobeDocs Film Festival (it opens today at the Kendall), I spoke to White about the rovers’ inspiring mission, what the state of Mars can tell us about climate change, and the perfect robot wake-up playlist.

BOSTON HASSLE: What drew you towards telling this story?

RYAN WHITE: Well, probably not surprisingly, I was a huge space nerd. I always wanted to be an astronaut, which I think is not rare– I think probably half of kids want to be that– but I always wanted to be that or a filmmaker, and I became a filmmaker (spoiler alert!). And I love my job so much because it takes me into the strangest places that I should never be allowed. I always would say to my producing partner, Jess Hargrave, “We have the one job where we could probably con our way into space at some point. Like, we could probably figure it out.” I always wanted to make a space film, even if it didn’t involve going to space. We’re very, very picky and selective with our projects because they take years to make, so we had said no to a lot of space stories that I loved, that really gutted me saying no to, but they weren’t character-based. And then this film was presented to me by Film 45 and Amblin Entertainment, which is Spielberg’s and Pete Berg’s company. Jess and I were at dinner with them, and we looked at each other– right away we were like, “This is the one. This is the space story.” Because we really like making character-based films, and even though two robots are the central characters, they are characters.

BH: I was impressed at how much footage there was of mission control from the time. I’m sure a lot of that was NASA footage, but what was the process like taking all these mountains of footage and converting them into a storyline with dramatic scenes?

RW: It was incredibly laborious. It was almost 1000 hours of footage that we got from NASA. I had a huge team of people, all the way down to college interns who were watching footage day to day. Most of my films previously were verite films, following something unfolding, so I know what it’s like to follow a lawsuit for six years, and be filming from morning ‘til night in a legal office, and nothing happens during that day. A lot of the footage is like that. It was verite filmmaking– there was an embedded cinematographer named John Beck-Hofmann who shot incredible footage for decades of this mission. It really was like a treasure hunt, looking for needles in a haystack of footage. And then when you find those moments like, say, ABBA playing “SOS” when Spirit’s gone missing, it’s the biggest reward in the world for having watched all that boring footage of someone just sitting at a computer for five hours.

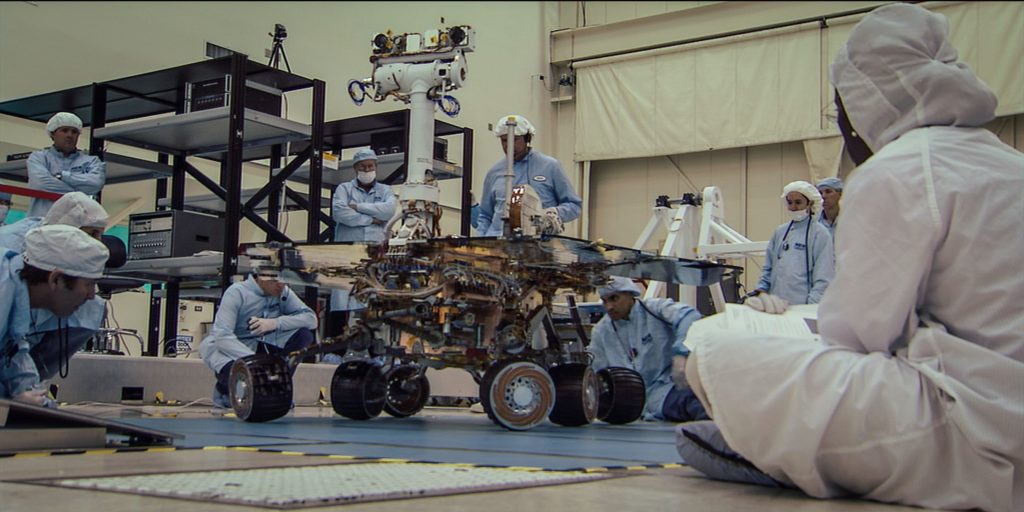

BH: Of course, in addition to the actual footage of the humans, so much of the film is the CGI reenactments of the rovers on Mars, and as you say the rovers sort of become characters that you feel like you know. Was it a challenge at all to anthropomorphize these machines, or did it come easily as the project came together?

RW: No, and that was one of the bigger challenges: how much? This is a true story. I’m not making a cartoon; it’s not Wall-E. I am a documentarian, and authenticity matters more than anything. Truth matters. So the big challenge was always, “We aren’t willing to anthropomorphize the robot.” That was always the conversation with Industrial Light & Magic, who did the visual effects. We can’t push reality. We can only anthropomorphize the robot as much as the people that our film is about are willing to. Jess would always joke, “We can’t put eyebrows on the robot!” How expressive can a robot’s face be when you’re limited to almost no movement, minus a little bit of a lens or aperture changing? We had to resign ourselves to the fact that we are trusting that the audience will bond to these robots without having to exaggerate the truth. We were always tied to the truth.

BH: I was struck by how many of the scientists and engineers also seem to be gifted storytellers. Were there any stories that they told that you wanted to work in, but didn’t make the cut?

RW: Oh, my God. So many! We would always say, “We have to get to Mars soon,” because we wanted the film to be accessible, especially to kids. We knew the longer you spent on Earth in more of a traditional documentary, archival format, the more a child audience probably would be tested in sticking it out. So we would always be like, “We can’t get to Mars at minute 45. We have to get to Mars in the first 30.” So we had to cut out a lot. We had a ton of backstory about NASA’s missions before this.

One of my favorite personal backstories is Doug Ellison, who’s the British guy in our film. He was working for a medical equipment company in a small town in England, and was a massive space geek and was following Spirit and Opportunity’s missions. One thing that was really revolutionary about this mission was Steve Squyres, the lead scientist’s goal was (that) when these robots took photos, they were immediately published to the internet. And Doug was this armchair-detective internet sleuth in small-town England that would stitch together the photos that they were taking to create these panoramas of what all of Mars in front of Opportunity would look like, and he was so impressive that NASA started using his imagery to chart the journey of Spirit and Opportunity. “Oh, this guy in England put this all together, we can go there today!” And they ended up hiring him. They brought him over; now he lives in Pasadena, and he’s one of the engineering leads on the cameras on Curiosity and Perseverance.

So we had a lot of those backstories. Jennifer Trosper– she’s the blonde woman in our film, who was there from the beginning– she was Spirit’s mission manager. We had a whole story about what it was like for her in the ’90s working at NASA in a man’s world, and how she got there. I wish there were still DVD extras! That used to be the gratuitous way of having your cake and eating it too. When you cut one of your babies, you’d be like, “Well, we’ll make it a DVD extra.” And unfortunately those don’t exist anymore.

BH: I’m not really a science person, and I never really considered that there would be the two factions working on the mission– the scientists on one end and the engineers on the other end. Did you find that they were these two different worlds, so to speak, that you had to coordinate between?

RW: It’s actually pretty cumbersome to always have to be saying, “…and the scientists and engineers who worked on her,” but those are two completely different jobs and two completely different missions. Like, the engineers love when the robots have trouble, and the scientists hate it. So a lot of the stories we would hear would be about that tension between the two. Steve Squyres always says that the proudest part of the mission for him is how those two teams came together. Because in a dream world, as a storyteller, you’d have a lot more drama. You’d have some sort of blowout fight that they had, a physical altercation at some point, (but) he’s like, “We both were so passionate about it, and so excited that it kept outlasting the odds.” He said he’s never seen a team of scientists and engineers work so well together.

BH: Whenever I look at a documentary about a story from the past– even though this isn’t that far past– I always try to connect it to contemporary events. I noticed that this sort of sits at the crossroads of two current events. On the one hand, you have these different interests trying to fly people to Mars, and colonize Mars. But on the other hand, I was struck by one of the scientists or engineers talking about how it’s kind of a cautionary tale: Mars had water at one point, and now it doesn’t, and that we don’t want our planet to go that same way. Is there anything that you hope that viewers take away from the film, watching in 2022 and going forward?

RW: I mean, that’s not why I make films. I’ve never made social issue films, or activist films. But I have made films that have social issues at their center– rather than just watching your characters’ journeys, some sort of larger themes, and this one I think is really interesting. I wasn’t trying to make a cautionary tale; I don’t even think I knew what Spirit and Opportunity’s scientific conclusions were when I said yes to making this film. But “cautionary tale” is a really apt term, I think. Every social issue, climate change included, is so politicized. I’ve never understood why it’s seen as political, or why you have to agree or disagree with it. But doing a story that is in some ways about climate change, but it’s about a robot– you can’t politicize a robot. A robot is a box of wires. It has instruments on it. It’s taking measurements, and it’s drawing conclusions from those measurements. And that conclusion, unequivocally, (is that) Spirit and Opportunity both discovered that water had existed on Mars. So I hope it’s a way of stripping the politics away and starting that conversation for anyone who might disagree that there’s climate change on Earth. It’s undeniable that there was climate change on Mars. We don’t know why, we don’t know when, we don’t know how– maybe there had been a civilization there billions of years ago, and they ruined their own planet. Or maybe it just dried up– we don’t know why. But I think it is a wonderful reminder of how special and precious our planet is– and precarious.

BH: As a final question, I’m as much of a music person as I am a movie person, so obviously one of my favorite parts was the wake-up songs that they would play for the rovers every day. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about that, and, more importantly, is there a place where one could find the complete playlist?

RW: Yes! There’s a Spotify playlist. NASA had an old Microsoft document that had the thousands of songs that they played for Spirit and Opportunity, and our team of interns put it together into a Spotify playlist. Unfortunately for me, it’s basically the entire canon of great pop music over the last 50 years– at some point a great song was played one morning because you had robots that lasted for years, two of them, and they were playing a wakeup song every morning for at least the first few years. So one of the hardest parts was… I’m not gonna say, but there’s a couple songs in my film that I just do not like. (laughs) But I had to be okay with being at the whim of the story, even if there’s a song that I hate that was played, (but that) played an important story role. Like, a song obviously that was played at some point was Bowie’s “Life on Mars?” And we had that at some point in our film, but we didn’t have it in a scene— we didn’t have footage of it being played ever. And I remember the day when we finally got rid of that song, and being so gutted. I’d be like, “Really? We’re gonna get rid of Bowie, but we’re gonna keep fill-in-the-blank?” (laughs) But I enjoy watching the film now because of that, because even though there are a couple of songs where I’m like, “I always hated that song,” it’s real. Like, “Born to be Wild” was the first song played, and you can’t insert “Life on Mars?” there if it wasn’t being played.

I think there’s six or seven songs in the film, incredible artists like Billie Holiday, Beatles, ABBA. That’s not normally a documentary’s soundtrack. Normally you can’t figure that out on a documentary budget, but thankfully all the record labels said yes. And I think that’s a testament to the heartwarming nature of this story. It’s like, “Yeah, we want our Beatles song to be in a story about a robot that outlasted the odds.” We were very pleasantly surprised with everyone saying yes to being in it.

Good Night Oppy

2022

dir. Ryan White

105 min.

Opens Friday, 11/4 @ Kendall Square Cinema

Streaming on Amazon Prime 11/23