When describing the reasoning behind the performance Harvesting the Divine Feminine, dancer NaShaya Wornum explains: “we need to bring culture that isn’t just European to this area […] so no one is totally lost.” When she says this, I refocus my gaze outside to the throngs of people snapping crabs and drinking beers, almost swallowing this small corner-space gallery. It is clear what she means. The Fort Point Arts Community Assemblage Gallery is nestled in an area of Boston that is almost 90% white, and on one of the warmer, sunnier days of June, swarms of pressed khakis and pristine polos congregate just outside of the gallery’s walls. It is a weird feeling to have people watching us watch Wornum perform—the glass provides an apt example of what she seems to be getting at. While she is technically visible and performing in the space, there is an unspoken separation between what’s being addressed here and what is happening outside.

The exhibition Be/Come features the work of Emily Brodrick and Kate Holcomb Hale, two artists who are keenly aware of the precarious placement of the Assemblage space in Fort Point. In fact, their exhibit aims to highlight just that: the title itself suggests a tension between stasis and progress, and both Brodrick and Hale take this for their creative inspiration. The version of Be/Come I experienced was particularly special, as it featured the work of coppersmith T. Michael Thomas, Imani McFarlane, designer and CEO of Seaport-based Tafari Wraps and a performance by NaShaya Wornum, who describes herself as “a young, black artist who has only truly begun to come out of her shell.” As such, this piece will focus on the exhibition as a whole, as well as the specific works by Wornum and McFarlane on June 12th.

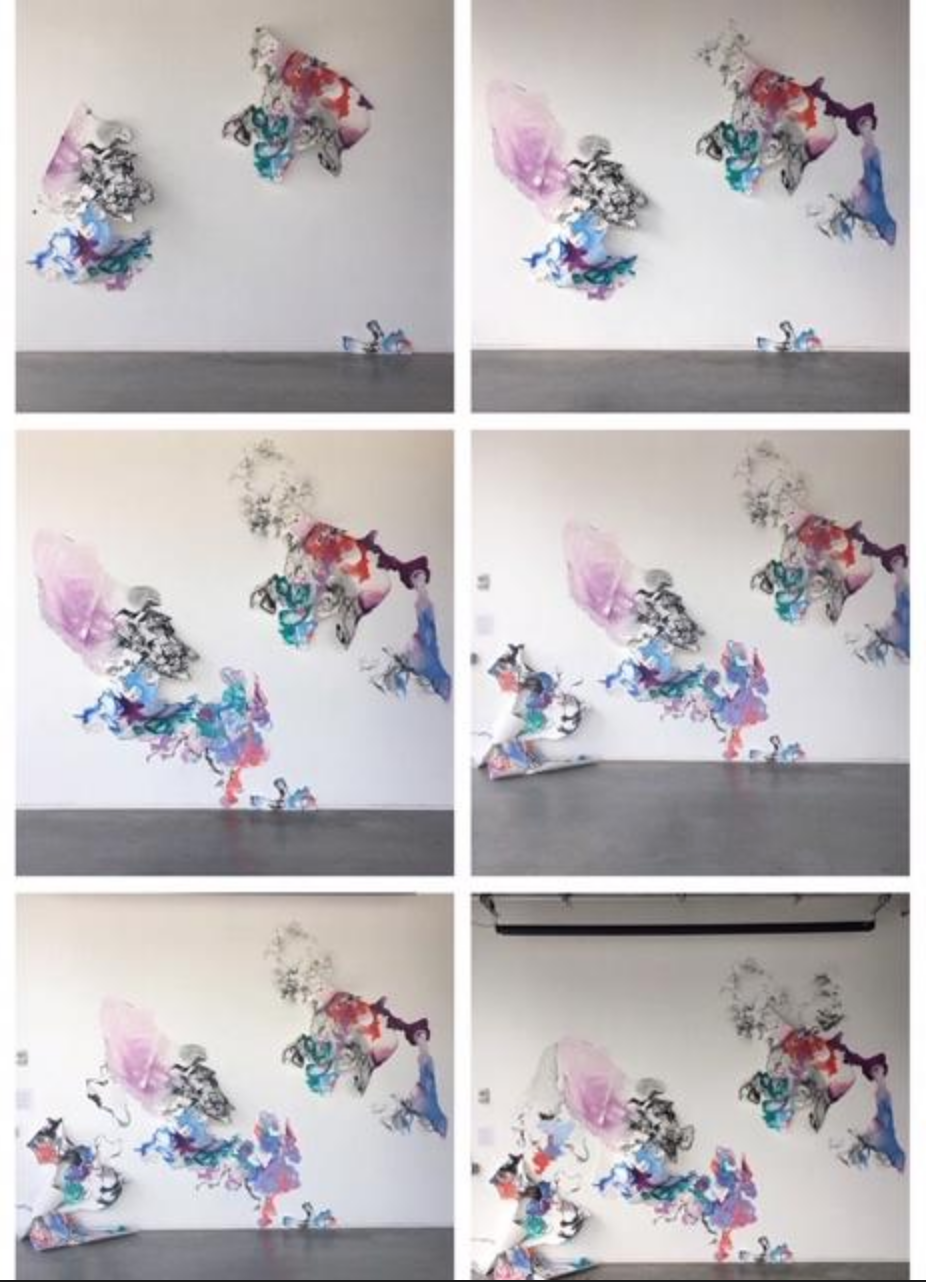

Be/Come showcases the continued artistic process, played out in a gallery space in conversation with viewers. “That is the beauty of asking for feedback and why we both wanted to have a suggestion box,” explains Brodrick, “to get ideas that we couldn’t have thought of ourselves, good and bad.” Walking into the sunlit space on Sleeper street, it is immediately apparent how much the exhibition has been shaped by a balance between intention and abandon. Hale’s pieces swoop, twisting and curving as paper meets paint meets the pale of the gallery walls. Movement is crucial in both Hale and Brodrick’s work. Hale’s pieces seem to crawl across the wall, without bounds or borders. Where Hale’s work evokes a slower, more gradual progression in the space, Brodrick’s work is almost biological, even cellular—it proliferates.

Kate Holcomb Hale, progression of I’m not here for the left leg. I’m here for right foot. Image courtesy of the artist @kateholcombhale

As Hale gamely acknowledges in her documentation of the exhibition on Instagram: “this show could also be called ‘mistakes were made.’” After speaking with Hale at Fort Point Arts Night, I sensed the importance of this kind of openness to so-called “‘mistakes.’” Hale and Brodrick build on the exhibit using feedback cards from visitors. “I had to embrace the idea of incompleteness,” says Hale, “I realized that whether I was satisfied or not with what I had created that day I had to leave it unfinished. All my missteps were on view. It was hard to take big risks with the work because I felt vulnerable that when things went wrong, it would be there for all to witness. Eventually it became easier. I became more at ease with the idea of my works being incomplete/in-process and embraced the beauty in the unfolding that occurred as I worked slowly.”

Hale also found the communication of Be/Come’s premise to be a process in itself: “I think viewers took the work at face value unless they delved deeper and read the materials. Also seeing us working seemed to be a hurdle for people. Visitors wondered if we were installing/if show was open yet and hesitated to come in the gallery.” Ultimately, however, she feels that “people seemed into the concept and were curious as to how the work would evolve by the end of two months.” The progression of Hale and Brodrick’s work heralds more than a fresh burst of creativity on the Seaport scene: they have captured the process of communication in action, and have done so in a most crucial place and time in Boston. As Brodrick puts it: “It’s not often that artists are allowed the time and space to basically transform a gallery into a slowly growing immersive installation.” Brodrick’s description of this artistic license and freedom directly relates to the overarching goal of the exhibit: to return a sense of agency to artistic communities (and particularly the black, female voices within them) who have been affected by the growing gentrification of the Seaport area and Boston as a whole. This is where McFarlane and Wornum’s joint performance comes in. “Their performance in the gallery added another layer to the exhibition,” explains Hale, “infusing it with positive female embodiment, more diverse voices (which I am aware had been totally lacking) and movement/dance that paid homage to their shared history and culture.” To take further advantage of what Brodrick calls “this little fishbowl of culture in an otherwise pretty vacation-centric location,” she and Hale invited McFarlane and others to share the space for a special night of performance infused with Afro-Caribbean culture and sensibility. “[Be/Come is] a stronghold, in a sense, of our own personal experiences as women and artists.” Harvesting the Divine Feminine, then, is a particularly powerful concept to bring into the space.

Kate Holcomb Hale, But she seems so easygoing (left) and Emily Brodrick, Interfuse, slowly growing towards each other.

NaShaya Wornum’s performance of Harvesting the Divine Feminine, conceived by Imani McFarlane and featuring McFarlane’s traditional headwraps, is centered around three shrines to what Wornum describes as “Home, Harvest, and Food.” The performance traces the cycle of the Divine Feminine, from the hearth to harvest to the provision of emotional, spiritual, and literal food that characterizes the feminine self. Wornum stresses the delicate interdependence among the three realms: without sustaining (“feeding”) the self, a woman is unable to yield a bountiful harvest, and in turn is unable to properly provide for herself and others. Thus, while traditional notions of femininity as a nurturing and giving force are important aspects of the performance, Wornum and McFarlane make it clear that self-empowerment, sustenance of the self, are equally crucial pillars of the Divine Feminine. Set to several tracks, including “Eleggua: Intro” by musical duo Ibeyi (meaning “twins,” a venerated phenomenon and specific spirit in Yoruba culture,) the performance is both rebellious and deeply reverent. At the start and the end of the piece, Wornum circles each shrine and performs several supplications. One shrine (I noted, thrilled to make use of my “what are you going to do with that?” religious studies major,) indicated the presence of Elegguá himself. Multiple African Diaspora religions, including Santería, Umbanda, and Candomblé, worship overlapping deities called orichas or orixas. Elegguá, deity of the crossroads, was the first of the orichas to be created by the supreme spirit Olodumare. Elegguá can be identified by a necklace of black and red beads and the presence of a coconut and cowries (often used in divination practice) among other things, including bottles of strong alcohol which are one of his preferred devotions. At the start of her piece, Wornum took a sip of alcohol and sprayed it over the shrine, a gesture of reverence that would perhaps enable her to continue the performance. It is not an accident that Ibeyi’s album begins with an invocation of the deity as well—in Santería and other religious practices, Elegguá must be appeased before any other sort of ritual or performance is undertaken.

What I always found most striking in my study of religions of the African Diaspora was the expansiveness of these religious practices. Many elements of religions in the diaspora can be looked to as embodiments of the kind of openness Brodrick and Hale are attempting to bring to the space, and which was embodied so electrifyingly in Wornum’s performance. This dynamism of doctrine and praxis was borne of necessity, a testament to both the painful history of diaspora religions in the Atlantic Slave Trade and the strength and creativity in their spiritual solutions to new world experiences in the Americas. Both McFarlane’s designs and Wornum’s performance clearly follow in this same tradition. “Drawing on African spirituality,” details the press release for Be/Come, “Imani [McFarlane] designs and creates headwraps that are not only fashionable in their artistry but healing in function.”

“Through Be/Come we wanted to open up conversations about change and movement in the seaport and what that has meant for artists/residents,” explained Brodrick, “I think Imani and NaShaya’s performance Harvesting the Divine Feminine speaks to a greater conversation of movement and change within black communities in Boston and how gentrification has affected them, specifically in the case of this performance as local artists and women of color.” Hale agrees: “I think Nashaya Wornum and Imani McFarlane’s performance completely energized the space in a way I didn’t expect. While the burden of the black female body is one steeped in a rich and difficult history the balancing of women’s roles as ‘mother – sister – lover – caretaker – friend – community leader’ can be seen as universal to women. I imagine it resonated with many women in the gallery that evening. It definitely did for me.”

The notions of movement and process highlighted by Hale and Brodrick in Be/Come, both physical and metaphorical, are deepened by the choice to bring the wider nexus of religious, cultural, and social influence in which African diasporic religions are continuously constructed into the gallery’s walls. In the final section of her performance, Wornum carefully places one of McFarlane’s wraps on her head. The end of her performance is set to “Everybody Loves the Sunshine” a 1976 song by Roy Ayers most notably featured in Spike Lee’s updated version of She’s Gotta Have It on Netflix, which deals with a similar intersection of art and gentrification in Fort Greene, Brooklyn and also features elements of Santería. The questions that drive Harvesting the Divine Feminine are incredibly relevant to other intersections of race and artistic space being navigated today: “what does it mean to be a feminine black woman?” asks McFarlane, “What does her strength look like? How does she stand? Walk? When she is happy, what does that look like for herself and her community? When she is challenged, how does she overcome those adversities to provide for herself, and her community? Who gets to be feminine, and what power lies in the balance of the divine feminine/masculine?” Wornum’s embodiment of these questions filled the space, adopting a similar sense of both reverent intention and utter abandon in an exploration of the self that set the tone for the exhibition as a whole. “The black female body forever shifts, transcending space and time,” she explains, “she awakens memories that have shaped her, preparing her for the path ahead.” Ultimately, McFarlane, Wornum, Brodrick, and Hale work in tandem to bring conversations around art and community in Fort Point into Elegguá’s domain: crossroads, places of transition and change, and the immeasurable potential to be found there.

A closing reception for Be/Come will be held at the FPAC Assemblage Gallery tonight, June 27th. More information on the exhibition and the event can be found here.