THROWBACK: KING IN COOPER’S BOSTON

A snapshot of the Hub in MLK’s day

BY PETER ROBERGE OF DIRTY OLD BOSTON

Eight years before Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his “I Have A Dream” speech in 1963, a young MLK earned his doctorate degree here in the hub, specifically his PhD in systematic theology from Boston University. From the official BU archive, which holds a number of critical documents from the period:

Graduating from Morehouse in 1948, King went on to study at the racially integrated Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania. One of only six African-American students, he proved to be a superior student, even electing to take supplemental courses in philosophy at the nearby University of Pennsylvania. It was while studying at Crozer that King became an admirer of the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi, and he adopted Gandhi’s stance that nonviolent resistance could be used to channel anger and frustration into a more positive force for societal change.

Upon completion of his degree, King was awarded a fellowship for graduate studies, and he enrolled in the doctoral program at Boston University, supplementing his course work with philosophy classes at Harvard. He completed the academic requirements in 1953 and turned to completing his doctoral dissertation, “A Comparison of the Conceptions of God in the Thinking of Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman.” In June 1955, he earned his PhD. During the summer breaks while in graduate school, King returned to Atlanta where he would preach sermons at the Ebenezer Baptist Church.

As you might imagine, race relations at the time in Boston were extremely volatile. By many accounts, MLK’s resolve came into focus in these parts, as he would in short time go on to help lead Civil Rights leaders across the country. On that note, let’s jump back to the ’50s, and to some of the developments he would have seen during his time here …

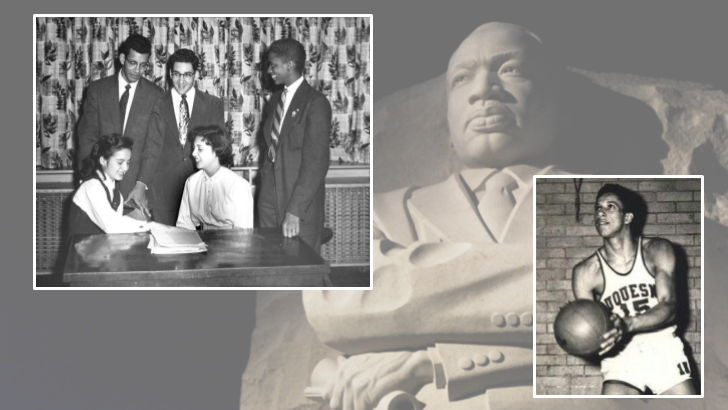

The Celtics became the first team in the NBA to draft an African-American player with the selection of Chuck Cooper in 1950. The history of Cooper with the Celtics may be less well known than Jackie Robinson’s groundbreaking foray into Major League Baseball, though it was a critical and telling moment for New England and the country as well. With Cooper on the roster, several other teams refused to play at the Boston Garden, while in certain cases clubs refused to let the Celtics in their home arenas. Tensions even escalated into violence, with a fight erupting between Cooper and a Tri-City (Illinois) Blackhawks player who hurled racist insults at him during a game.

Despite such drama, both locally and nationally, when asked about the controversial addition to his team, then-Celtics coach Red Auerbach told sports reporters, “I don’t care if he’s striped, polka-dotted, or plaid.” Cooper’s career with the team ended in 1954 when, interestingly, he was traded to the (Tri-City) Hawks.

In Boston’s African-American neighborhoods, groups began organizing in unique ways to improve their communities around the half-century mark. There were already some supports in place — such as the American Federation of Musicians Local 535, which started representing black musicians from Boston and elsewhere starting as early as 1915, and the Boston branch of the NAACP, founded in 1911 — but with new momentum came new outfits. One that stood out was the Roxbury Youth Council, operating out of Freedom House, which was founded in the Grove Hall area in 1949. As Bostonians lent their voices to the growing Civil Rights Movement, such organizations provided a space for organizers and thought leaders. With help from the well-known likes of Jackie Washington, a folk musician born and raised in Roxbury, the youth council facilitated teenage residents in offering their feedback to the city about race relations among other issues.

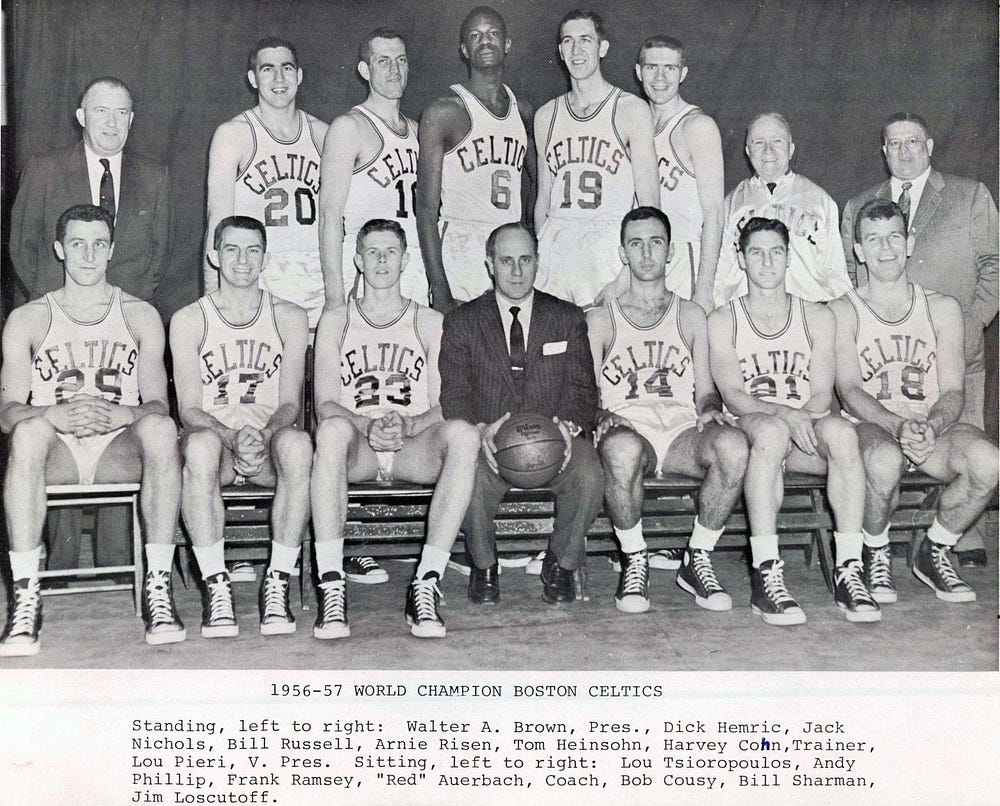

As for the Celtics, you probably know how that story continues. They signed a second African-American player, Bill Russell, in 1956. It was a time for cultural transition, with the suburbs becoming increasingly popular and attracting wealthy, predominately white families, and leaving a city divided along strict racial and ethnic lines in their wake. Racist commentators blasted Russell for, among other things, speaking “Muslim nonsense.”

Unlike his critics, however, Russell went on to become one of Boston’s most beloved heroes.

This Article originally appeared on BINJ’s medium page on January 14, 2018. It is being re-posted here with the consent of that fine organization.

VISIT_DIRTY_OLD_BOSTON_ON_FACEBOOK