The internet is weird.

I don’t mean that the stuff on the internet is weird; it is, of course, but that’s not what I’m talking about right now. Rather, I’m referring to our relationship with the internet, and how it’s portrayed in other media. At this point it’s not an exaggeration to say that many of us spend the majority of our waking hours online in some capacity or another; if you’re reading these words, you’re doing it right now, gazing into a glowing rectangle on your desk or hunched over a palm-sized piece of glass on the toilet. The only people who aren’t online, it seems, are movie characters. They’ll talk about it, dropping casual references to “going viral” or “swiping right” or some other semi-topical buzzword, but we rarely see them in the act; when we do, it’s always some off-model Google clone that’s just a little too clean to be believable. It may be a question of cinematics– you try to dynamically film a person clicking on links and typing “lol.” Or, perhaps, we just don’t like to admit to ourselves how many hours of our lives are spent listlessly scrolling and refreshing. Movies don’t always need to be escapism, but it’s nice to see someone who’s slightly less of a loser than myself.

In the annals of Internet Cinema (which can be traced at least as far back as 1983’s War Games), few capture the actual feeling of Being Online than Jane Schoenbrun’s found-footage horror-whatzit We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, which played to raves on the festival circuit last year and finally makes its local theatrical debut this week at the Brattle. It’s a haunting work, melancholy and more than a little frightening– though maybe not for the reasons you might expect going in.

The setup is pure creepypasta: young Casey (the remarkable Anna Cobb, in her screen debut) is a sad-eyed teen who finds herself drawn to the “World’s Fair Challenge,” a Bloody Mary-style viral phenomenon in which participants repeat a chant (into their webcam, or it didn’t happen), prick their finger, and watch a strobing video, then record the changes they find themselves experiencing over the days and weeks that follow. The exact nature of these changes seems to vary from person to person; in Casey’s case they seem to manifest in sleepwalking and random, seemingly uncontrollable outbursts. Her videos attract the attention of a fellow user who identifies himself only as “JLB” (Michael Rogers), who may or may not know something about the true nature of the challenge. But is Casey’s behavior a symptom of demonic possession, or simply the bored mind of an internet-addled little girl?

Ordinarily I would leave this as a tantalizing rhetorical question, but in the case of We’re All Going to the World’s Fair I find myself in something of a bind. This is a film that invites analysis, but it’s also a film which should be first approached as blind as possible. So if you’re reading because you’re wondering if you should check it out, the answer is yes– it’s one of the most intriguing and complex films you’re likely to see this year– but I’m going to ask you to bookmark this review and return to it after your viewing. It’s a film worth talking about, but also one that deserves to be taken on its own terms. So if you have not yet seen We’re All Going to the World’s Fair and are interested in doing so, please stop reading… now.

So what is the World’s Fair Challenge? For all purposes that matter, it’s just a silly creepypasta MMORPG, the sort that you yourself could easily enter right now by clicking over to Reddit or 4Chan. There is nothing in Casey’s videos that explicitly suggests the supernatural, and everything to suggest that she is just a sad, lonely kid on the internet. Likewise, JLB is just a sad, lonely dude on the internet, albeit one with a vaguely unseemly fixation on a minor (at one point Casey angrily ends a chat by calling him a pedophile, and one suspects she may be onto something). When all is said and done, this is a fairly down-to-earth story, one which is likely playing out right now in countless family computer dens across the country.

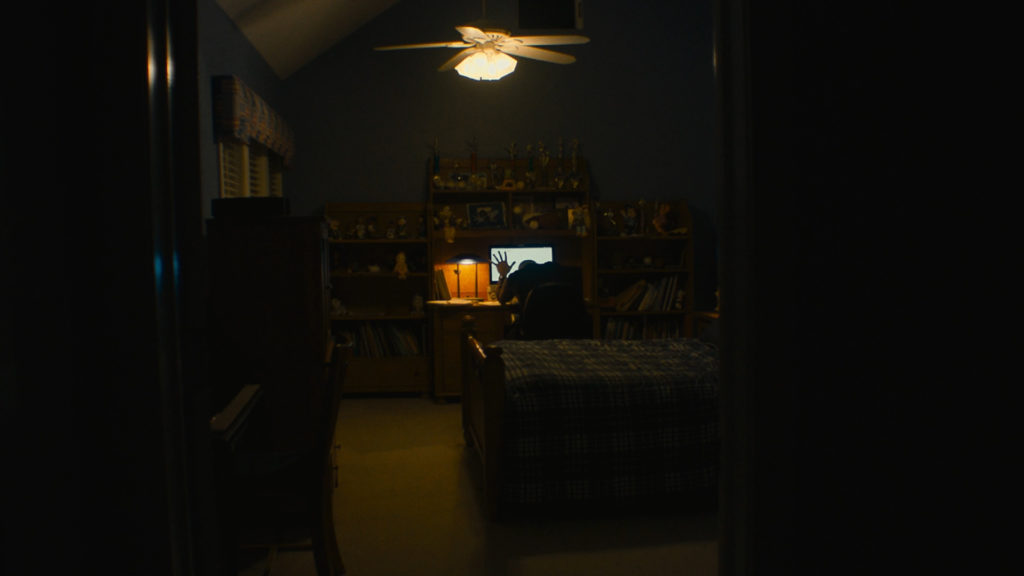

I have said that this is likely not a tale of the supernatural; I have not said that this is not a horror movie. Upon second viewing (which is recommended), World’s Fair reveals itself as a portrait of teenage alienation which is both deeply harrowing and eminently relatable. We don’t learn much about Casey’s offline life– the only in-person interaction we’re privy to is her father angrily yelling through the door to turn off the Youtube and go to bed– but we see enough to glean that she’s not in a particularly good place. Her outbursts– if they’re not supernatural– often read like cries for help, and she makes troubling references to the gun her family keeps in the toolshed. Her hometown is a drab expanse of off-ramps and shuttered big-box stores, with nothing to distinguish itself from any other late-capitalist swath of the country; as Schoenbrun said last year in an interview with the Hassle’s Kyle Amato, “The vagueness of her landscape is a plot point.” The internet, then, is Casey’s only lifeline. We never learn quite what she’s seeking– excitement, attention, something resembling community– but, like millions of kids across the country, she knows the internet is her best shot at finding it. That it doesn’t seem to offer much help shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone who’s ever used the internet.

For all the film’s horror trappings, what Schoenbrun has created is one of the most grounded and realistic portrayals of online life– which is to say, modern life– I’ve seen on screen. The World’s Fair videos Casey watches are just as variable in quality as an actual Youtube playlist, ranging from the artfully aesthetic (a young woman who claims to be turning into a life-size Barbie doll) to the uninspired (a dude sitting on his bathroom floor describing an incoherent nightmare about Tetris blocks) to the cheesy (what appears to be a clip from a fictional movie about the challenge). These clips shade in our understanding of the world of the film, but they’re presented with as little context as an algorithm (separated only by a deadpan loading wheel); like Casey, we are left to connect the dots ourselves.

Or, more accurately, like JLB. One of the most surprising things I realized on my second viewing was that, though Casey is the film’s emotional core, JLB is our true surrogate; we don’t know much more about her than he does, and like him we spend most of the film scanning Casey’s videos for clues about what’s really going on with her. JLB’s scenes are unsettling– this sunken-eyed, middle-aged wastoid padding around his house and staring at a teenager’s videos– but all the more so when we realize how much they resemble our own waking hours. Toward the end of the film, JLB delivers an epilogue of sorts (off a notes app, into a webcam), but it’s not clear whether the events he described actually happened or if his monologue merely represents wishful thinking. He’s the audience, after all, and audiences seek narrative closure.

The internet has long been full of scary stories and shock sites, but it also possesses a more existential horror. Anyone who’s spent any time in an online forum has likely experienced the dull, uncanny dread of a one-time regular– a “friend,” even– who suddenly vanishes off the face of the earth. Did something awful happen to them, or did they simply get bored? In more than one video, Casey repeats, “Someday soon I swear I’m gonna disappear, and you won’t have any idea what happened to me.” This, more than Momo or Slender Man or any other cyber-age bugbear, is the true horror of the internet, and Schoenbrun is the first filmmaker I’ve seen to fully recognize and express this. We’re All Going to the World’s Fair is a quietly epochal work, and one which I suspect will be discussed for years to come.

We’re All Going to the World’s Fair

2021

dir. Jane Schoenbrun

86 min.

Theatrical premiere run – screens Friday, 4/22 through Wednesday, 4/27 @ Brattle Theatre