One of the less-discussed bummers of the annual Awards Season Slog is how the nominees of certain categories tend to be flattened and minimized rather than elevated. Persuading the typical English-speaking American to dip a toe into international cinema is, of course, an uphill battle to begin with; even a wildly populist piece of blockbuster entertainment like RRR is sure to be viewed in certain circles as the cinematic equivalent of eating one’s vegetables. To be sure, this is changing to some extent, thanks both to shifting demographics and easier access to films that were once confined to metropolitan arthouses and more adventurous video stores, but even today there is a drive among cinephiles to prioritize the films that they “have” to see. This field is methodically whittled down throughout the Oscar nomination process: first by the field of titles presented by each country as their official submission (a politically fraught process which tends to exclude more incendiary works like RRR and Bacurau), then by the preemptively announced shortlist, and, ultimately, the final slate of five nominees. And even among those, a frontrunner inevitably emerges, leaving its also-rans in countless Oscar-watchers’ “I still need to get to that” piles.”

This year, the unequivocal frontrunner is Edward Berger’s Netflix adaptation of All Quiet on the Western Front, a Hollywood blockbuster in all but language which has managed to rack up nominations in a remarkable eight other categories. Waiting in the wings as a potential dark horse (donkey?) is Jerzy Skolimowski’s EO, the clear critical favorite of the group. There is, sadly, little path for Colm Bairéad’s The Quiet Girl, which finally opens this week at the Coolidge Corner Theatre. But I truly hope it finds its audience, because it’s easily one of the most affecting films of the year.

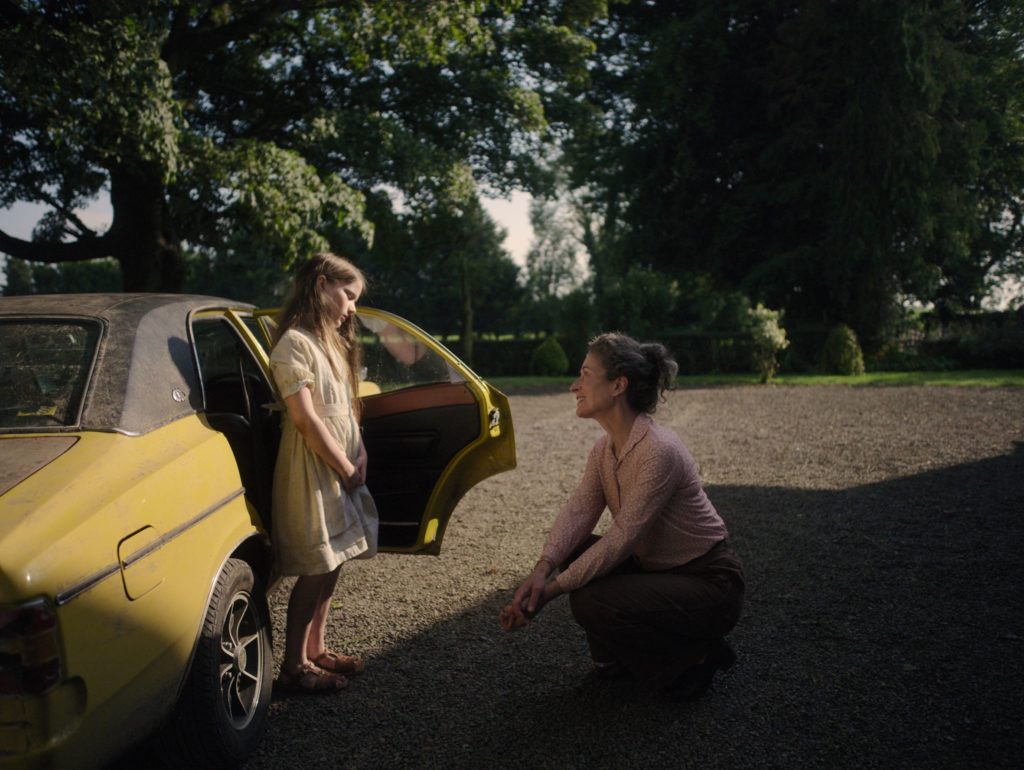

Nine-year-old Cáit Cháit (Catherine Clinch) is the “problem child” of her large family: a chronic bedwetter, withdrawn by nature, and given to run away from school or home when the fancy strikes her. Her father (Michael Patric) is clearly not particularly interested in caring for his brood (imagine if Paul Mescal’s in-over-his-head young father from Aftersun was a mean drunk), and her mother (Kate Nic Chonaonaigh) is at her wit’s end; neither of them have the slightest sense of how to deal with Cáit, especially with Baby #6 on its way. In an attempt to outsource their parenting woes, if only temporarily, the Cháits drive Cáit out to the remote family farm, where her aunt and uncle will take care of her until after the baby is born.

It is clear from the moment Cáit arrives that her Aunt Eibhlín (Carrie Crowley) is a presence unlike any Cáit has felt in her short life, her warm smile and twinkling eyes conveying a familial love altogether lacking in her biological parents. When Cáit inevitably wets the bed on her first night at the homestead, Eibhlín puts her hands on her hips and exclaims “Why, these old mattresses always be weepin’!” Her uncle, Seán (Andrew Bennett) is initially more stand-offish, but as Cáit settles into farm life he begins to appreciate her company, teaching her how to milk the cows and encouraging her to beat her speed record as she runs to the end of the drive to check the mail. “No secrets in this house,” Eibhlín tells Cáit, “If there’s secrets in a house, there’s shame in that house.” Cáit eventually learns, of course, that this isn’t quite true– why do her childless relatives have a room set up for her, complete with clothes and toys?– but the kindness of her relatives allows her to blossom in ways no one in her life back home ever dreamed possible.

The Quiet Girl is perhaps the most accurately titled of the year. This is not to say that it’s “slow cinema,” per se– it moves fairly briskly across its lean 95-minute running time– nor is it without drama; indeed, the deep sadness of its characters is at times almost overwhelming. But even in its most heartbreaking moments, there is an inviting gentleness that softens the blow. The film is shot in muted but appealing tones, and the characters– not just Cáit, but virtually every adult she comes in contact with– say more in their silences than they do in words. The Quiet Girl is about as unshowy as films come– which probably means it never had a chance at the Oscars, but which makes it a welcome alternative to today’s array of headachey, algorithmic sludge.

This gentle aura is enhanced by the fact that The Quiet Girl was filmed in the Irish language, also known as Gaelic, a tongue which I’ll confess I was unaware was still in active use, but which is still spoken conversationally by about 73,000 people in some of the more remote parts of the country. The Quiet Girl is set in 1981 (as evidenced by the cars and TV shows, as well as Mr. Cháit’s fashion sense), but the lilt of the language and the pastoral nature of the farmhouse seemingly place it out of time. Cáit does not encounter anything resembling the supernatural (as in 2021’s similar-in-tone Petite Maman), but it scarcely matters; compared to the drab confines of her own home and school, the farm might as well be Fairy Land.

It should go without saying that a film like The Quiet Girl hinges on its central performance, and Clinch– astoundingly, a first-time actress– is nothing short of captivating. Cáit is a role who could easily be overplayed as a wild-child caricature or underplayed as, well, a Quiet Girl. Instead, Clinch smartly plays the part primarily through her eyes, which effortlessly convey both an ocean of confusion and sadness and an every-child naivete. An American film would likely demonstrate Cáit’s growing sense of trust and attachment to her newfound caretakers through dialogue or a big, emotional setpiece; instead, we witness this change in real time as Cáit becomes visibly more relaxed and confident in herself and her surroundings. You don’t feel like you’re watching the performance of an actress, but the development of an actual little girl.

Make no mistake: The Quiet Girl is a very sad film, leading up to an ending so bittersweet that it’s almost difficult to watch. But, crucially, it’s never depressing. This is a story about kindness and found family, and about the sort of encouragement that leads one to come into their own. In the film, as in real life, there is no easy resolution, but there is also hope. The Quiet Girl may not win the Oscar (although crazier things have happened), but, for the right person seeing it at the right moment in their life, it could be the most important film in the world.

The Quiet Girl

2022

dir. Colm Bairéad

94 min.

Opens Friday, 3/3 @ Coolidge Corner Theatre