This is Part 2 of 2 in a series examining the religious filmmaking and visual theology of Paul W.S. Anderson. In the first piece, Anderson is postured as a religious filmmaker who deserves critical attention to that aspect of his filmmaking. The following piece, using the theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher as a resource, is an auteur analysis of the visual grammar of Anderson’s films that argues his visuals invoke a sense of a “divine player” through their resemblance to the visual grammar of video games.

If Paul W.S. Anderson is a religious filmmaker, as I argued in Part 1, then critics and film writers, as well as religion and culture writers, shouldn’t ignore this aspect of his filmmaking. What follows—a breakdown of his unique style through the theological tools provided by Liberal theology—is just one possible interpretation of religion and spirituality in Anderson’s filmography.

The Artist as Theologian and Friedrich Schleiermacher

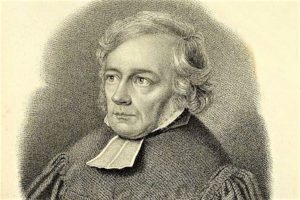

Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834), a divisive German Pietist theologian from the turn of the century a few centuries ago, is considered the patriarch of Liberal theology, and his articulation about the nature of theology provides a useful lens for understanding the style of Anderson.

He is arguably most famous for his articulation of religion as a feeling of utter dependence on the Divine. Because he didn’t think humans could have any direct knowledge about God, the task of the study of religion (which we will call theology, even though he doesn’t) is chiefly anthropocentric; to study theology is to study humans. But his idea of religious experience as a feeling of utter dependence is what concerns us here.

Schleiermacher—a leading figure in the German Romantic movement that included artists like Richard Wagner, Ludwig van Beethoven, Johannes Brahms, and a plethora of painters—was engaged with the arts of his time. He thought that the good theologian was really an artist, who through their art demonstrated the feeling of (divine) dependence to their audience. “Religion and art stand beside one another like two friendly souls whose inner affinity, whether or not they equally surmise it, is nevertheless still unknown to them,” he noted in his third speech in Cultural Despisers. The strong relationship connecting the two espouses from the way art can express, fulfill, embody feelings.

While Schleiermacher preceded the moving image by about a century, his words ring even truer about cinema. Film, as the great critic Roger Ebert famously observed, “is an empathy machine.” In Schleiermacher’s thought, while art can’t exactly replace religion, “art is a medium for religious communication,” as David E. Klemm puts it in his chapter on Schleiermacher in The Cambridge Companion to Friedrich Schleiermacher. Through this perspective, it’s arguable that Anderson is doing theology even if not as a theologian but as an artist.

The Visual Theology of Paul W.S. Anderson

One of the most noticeable and consistent stylistic traits of Anderson’s movies is the “God’s eye view,” a shot vertical and perpendicular to the camera’s subject, often a character, that contains no perspective referent. While not an uncommon shot in mainstream movies, Anderson’s use differs on a visual grammatical level from the shot’s traditional use of simply invoking an “omniscient” perspective that distances itself from the character’s point of view. For example, in one famous shot in Mission Impossible (1996), Tom Cruise’s Ethan Hunt drops from the ceiling in a heist while security guards walk around below him, making use of multiple layers of perspective alongside an omniscient perspective to induce more stress on the view. Another typical use is at work in the famous stairway shot in Psycho (1960), where the positioning of the camera implies the physical presence of another being. Martin Scorsese often uses the shot in a religiously inclined way by implying a “point of focus for a moral system.”

Anderson’s uses of the shot type—with great variety because of the abundance of examples in his work—differ in a few key ways.

These two images demonstrate typical uses of the shot type, with Anderson’s typical use (bottom) having less going on—they are often “lifeless.” The top image comes from Scorsese’s “The Last Temptation of Christ” and the bottom image from Anderson’s “The Three Musketeers.”

Notably, they often lack characters, such as in the establishing shot of the prison in Death Race, any number of the examples of the gravity drive in Event Horizon, or the tournament logo in Mortal Kombat. Lacking characters for reference, Scorsese’s use is muted and altered, though not absent.

His uses also differ in their implications for the audience. Many horror movies use them in a way that is evocative of an otherworldly being that could occupy physical space just behind the lens but doesn’t (something Anderson does on occasion). The perspectives here are implied, not real. (Horror more often uses such types of shots to imply an actual being, this is not the use I’m concerned with.) However, when it has human subjects, Anderson’s God’s eye view at first seems purposeless, especially with the frequency he returns to it. His protagonists, often played by his wife Milla Jovovich, aren’t as morally flawed or ambiguous as Scorsese’s. We hardly ever know anything about them, as I noted previously with Hunter and Alice. The shots also don’t appear to provide useful or stressful/humorous information from an “omniscient” perspective, as in the Mission Impossible example. They also, quite frankly, lack the “cool” factor that movies like Joker (2019) or much of the Marvel Cinematic Universe utilize them for because of their frequently inanimate focuses.

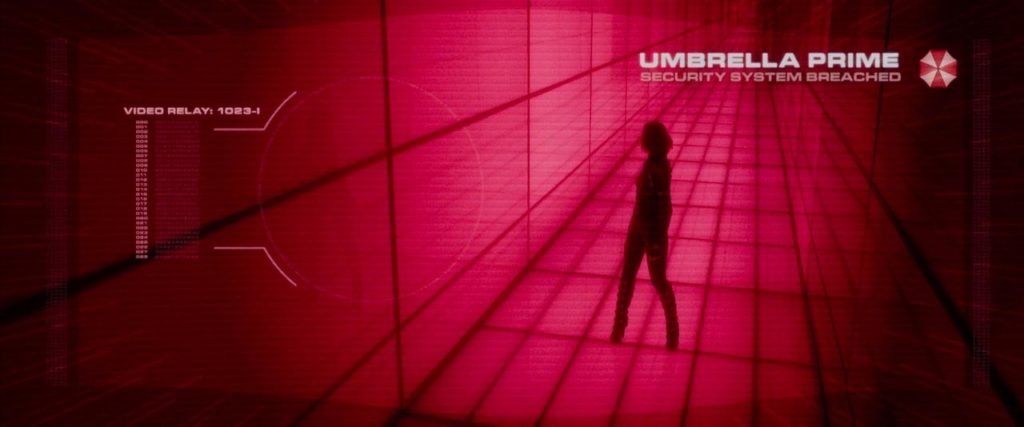

Mostly—but not completely—disengaged from the traditional grammar of its uses, Anderson’s God’s eye views, through the “eye” of the camera, invoke a being that lacks physical space, an omniscient perspective that observes with frequent care. It makes one feel as if someone is watching. Anderson frequently uses the shot in action scenes where the protagonist decisively proves victorious, such as in this screenshot from Resident Evil: Redemption. The result is the feeling that someone is controlling, or playing with, the subjects of the lens.

Screenshot originally from Resident Evil: The Final Chapter, but footage watermarked from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FLcPjtCbHWw.

Critically, the God’s eye view, for Anderson’s concerns, features prominently in third-person perspective video games, in which a physical person (the player) is controlling the content of the game. Given that nearly half of his films are video game adaptations, Anderson’s use of this shot type, separated from its traditional cinematic grammar, borrows instead from the grammar of video games: omniscient but acting upon the world, not taking up physical space but constantly present. To borrow from Schleiermacher, Anderson articulates a sense of dependency on a divine player: God.

There is a case to be made that this divine player aesthetic overflows into what, for a lack of better terms, can be called “visual geography.” Anderson’s recent critical reappraisal has largely been centered around his spatial and geometric awareness, particularly during action scenes. This paragraph from Isaac Feldberg’s interview with the director at Inverse provides a glimpse into what I’m talking about:

Though he approaches their execution seriously, there’s a refreshing lack of ostentation to Anderson’s action sequences; rarely does he linger on a sequence long enough to suggest he feels he’s done something properly artistic. In this way, Resident Evil and Jovovich are both perfect foils for the director’s style: unsentimental, laser-focused, and constantly mid-motion. Much like video games, Anderson’s films introduce elaborate game-boards his characters must maneuver; spatial and geographic considerations are prioritized over plot logic or emotional heft.

To oversimplify things: in his movies, the viewer knows where things are and it just makes sense, and Anderson never loses sight of that space when the scene is more kinetic.

Even when he works with original source material like Soldier (1998) his style is consistent with his “divine player” aesthetic, and so they look very much like video game adaptations.

If you’ve seen Jim Emerson’s tremendous video analysis of Christopher Nolan’s action filmmaking, it might be said that Anderson is Nolan’s antithesis.

Perhaps the most famous single scene in Anderson’s filmography, the first laser corridor sequence in Resident Evil, exemplifies this. Trapped in a corridor, the crew sent to stop The Hive sets off a booby trap when a lethal laser progresses down the hallway. A soldier is killed with every sweep, unable to dodge the laser like the others as it readjusts. In the laser’s third sweep, James “One” Shade (Colin Salmon) is trapped by space, unable to move forward or backward, when the laser morphs into a series of small diamonds that make it completely impossible to dodge. Anderson uses our awareness of physical space—the vertical and horizontal positioning of the laser that is down the hall along with our knowledge of where the soldier’s bodies are—to his advantage. When the laser goes low and the soldiers jump, the viewer is relieved and not surprised, since that was a possibility. But when James’s ability to transgress geography is frustrated—when the lasers turn into small diamonds—the viewer is shocked, an emotion created by his effective use of physical space.

A more unnoticeable trait of his films even relates to this as well: computer-generated map-inserts. As shown in this shot from Resident Evil: Retribution, when characters enter new locations, Anderson often breaks the dramatic flow to establish the new geography. This also seems borrowed from the grammar of video games. For example, at the start of a new level, it’s very common for a wide variety of video games to break the flow of the game by establishing the new location with a map insert of some sort. (Check out this scene from a Resident Evil video game for an illustration.) It allows viewers to track the geography of the world better.

So how does this relate to that Schleiermacher guy, visual theology, and feelings of utter dependence? In short, they function similarly to the God’s-eye view by pointing to the presence of a “divine player.” When players are inserted into the computer-generated maps, either to indicate their starting place or the path of their mission, they take up such little space that the map, by comparison, is inevitably colossal and daunting. Characters feel small in the worlds of Anderson, which are also populated by monsters, apocalyptic prison races, and zombies as seen in this clip introducing The Hive in Resident Evil, a few minutes before they encounter the first zombie.

If we recall Schleiermacher’s thought on the task of theology as something anthropocentric, this filmmaking is startling. Not only does his visual style evoke a sense of a divine player, or a controller of the happenings within the frame, but it is equated with the human perspective in the diegetic camera work– that is, shots from the perspectives of cameras that are in the world of the characters even if they are unaware of their presence, like the security cameras from The Hive in several Resident Evil movies.

This example of “diegetic camera work,” for a lack of better terms, comes from Resident Evil: Redemption.

In reference to how this connects with the divine player, perhaps the words of another philosopher-theologian somewhat similar to Schleiermacher, Ludwig Feuerbach, would help clarify: “Consciousness of God is self-consciousness, knowledge of God is self-knowledge.” Anderson consistently communicates this anthropocentric-theological view visually in his filmography by using a similar grammar in shots that call to mind the divine as with shots with a decidedly human element at the other end of the camera.

My goal isn’t to convince you that Paul W.S. Anderson is a theologian, in the tradition of Schleiermacher, who got stuck in the wrong field, nor would such a claim be believable. I do think Anderson’s work is ripe with material for religious analysis, his unique visual style might have something to do with it, and Schleiermacher is a helpful tool for thinking through said style.

But given the relationship between his visual style and its origins in the visual grammar of video games, when an interpretation connects it to the divine (or God), the topic of divine and human agency naturally catalysts itself into the conversation. Recent scholarship has argued in the vein that “videogames represent deterministic worlds in which players lack the ability to freely choose what they do, and yet players can be held morally responsible for some of their actions, specifically those actions that the player wants to do.” To put it simply, video game worlds are constructed uniquely compared to film in terms of ethical responsibility. As a viewer of film, you hold no immediate ethical responsibility for the content on screen. As a player, you do. Anderson’s style blurs this distinction—putting the moral ball back into the viewer’s lap.

I have no intention to argue for the effectiveness of this visual style, inasmuch as it actually induces viewers to contemplate the ethical reasoning on screen. I think it’s more appropriate and honest to argue that the visuals at least open room for a viewer to more actively consider the film’s portrayed ethical reasoning. Of course, the viewer must first be knowledgeable of the visual grammar of video games for this to even be plausible. I also speak from personal experience: I ended each Anderson film with a state of contemplativeness that I don’t experience with more typical big-budget action movies like Ant-Man and the Wasp. When Alice eventually comes to terms with the revelation that she is a clone in the final two movies, and is given what could only be described as a suicide mission to hopefully provide access to the vaccine to others, I felt ethically divided: humans are unique within Kingdom Animalia because of our ability to make moral decisions, and thus, for Alice to go forth with the mission, she would have to be human; simultaneously, her being incompletely human also justifies her expediency. Watching an Anderson action/genre movie, for this reason, is always a unique experience for me.

The blank slate characters are perhaps the key that holds this interpretation together. Alice’s six-film journey in the Resident Evil franchise starts with no memories of a previous life, as she wakes up from a Hive induced chemical defense system; as she gains memories back, Anderson only reveals information relevant to the plot, such as that she was involved with a scheme to tear down the Umbrella Corporation; her past is a complete mystery. Much like the start to an average action video game, she wakes as a blank slate. In video games, this allows for the in-game character to become an avatar for the user. In more morally complex video games, character decisions alter the play of the game itself, producing different outcomes. While Anderson doesn’t quite stretch his adaptations to that level, he does everything but by borrowing the visual grammar and narrative mechanics that contribute to this effect in video games. As such, what appears to be a mindless zombie-killing action flick on the surface, is anything but: it’s an art with the rhetorical power to make the viewer conscious of moral decision making and the divine.

The portion of this essay on Resident Evil: The Final Chapter is a reworking and summary of an earlier Letterboxd review by the author.

Excellent