Perhaps the wildest thing about the recent wave of posthumously released films by Orson Welles (completed and reconstructed by Oscar-winning editor and preservationist Bob Murawski) is how aware Welles was in his later days, both of his own reputation and of the way of the world. In his first “comeback” film, 2018’s The Other Side of the Wind, the larger-than-life Hollywood pariah told the story of larger-than-life Hollywood pariah Jake Hannaford, played by larger-than-life Hollywood pariah John Huston. Hannaford’s hotshot young protege is Brooks Otterlake, played by Welles’ hotshot young protege Peter Bogdanovich– who, himself, was just a few years away in real life from becoming a larger-than-life Hollywood pariah. Obviously, there’s no way Welles could have known this latter part, but one can easily imagine that he had a hunch. When you direct the consensus Best Movie Ever Made at age 25, then spend the rest of your career living in the desert trying to scrape projects together from your own pocket, you develop a jaded eye for Hollywood– and when you become a de facto mentor for a new generation of cinematic mavericks, you have no shortage of young upstarts on which to train it.

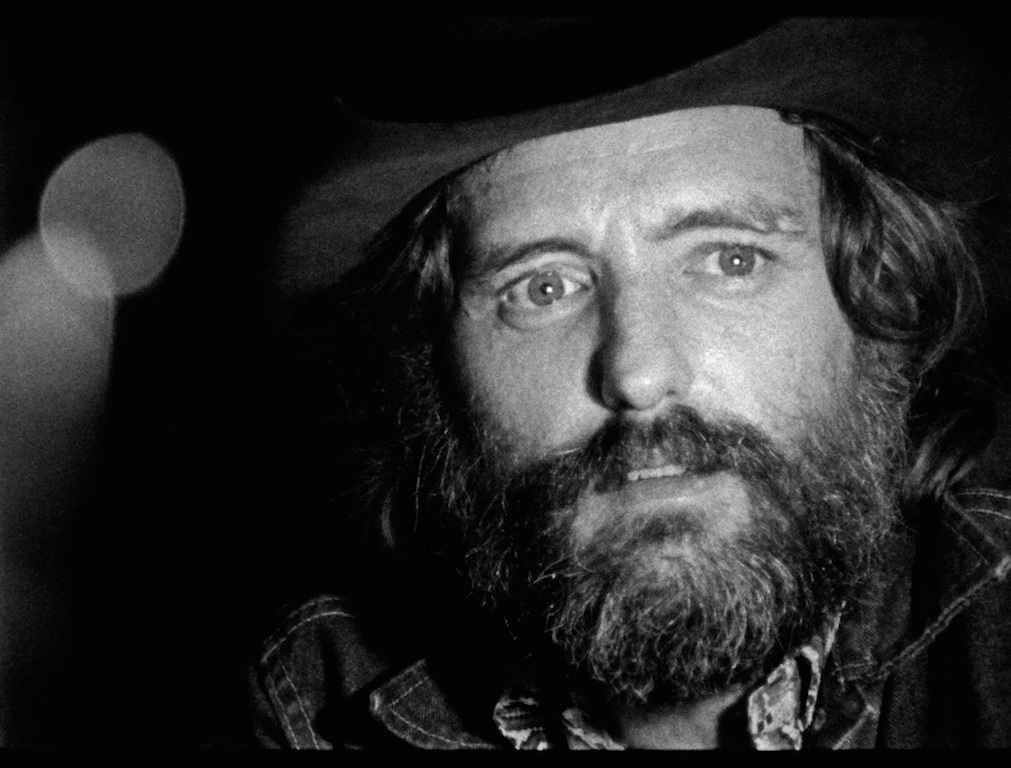

Among the new-Hollywood film brats to seek Welles’ wisdom was Dennis Hopper. Today, of course, Hopper is primarily remembered as one of film’s great character actors, the madman of Blue Velvet and Apocalypse Now and River’s Edge and Speed. In 1970, however, he was something more. After a decade and a half of bit parts and JD pictures, Hopper broke through in 1969 with the seminal hippie-biker-freakout film Easy Rider. It’s easy to forget just how radical Easy Rider was at the time of its release, a genuinely experimental independent film which captured lightning in a bottle and became a cultural touchstone (and colossal box office hit) in the summer of Woodstock. As both the director and star of the film, Hopper was positioned as something of a countercultural messiah– which Hopper, with his shaggy good looks and penchant for speed-freak philosophizing, was more than happy to play into.

Which brings us to Hopper/Welles, the latest abandoned Welles project resuscitated by Murawski. Initially conceived as either a companion piece or a subplot to The Other Side of the Wind, Hopper/Welles is, in essence, a two-hour filmed interview of Hopper by Welles, shot late at night at Welles’ estate over a mountain of empty bottles (it’s not clear how much of the setting is staged; to muddy the waters further, Welles occasionally takes on the character of Jake Hannaford, and Hopper frequently addresses him as such). Actually, “interview” is maybe not the right word; over the course of the running time, the conversation veers back and forth between a stream-of-consciousness late-night bull session and an interrogation, with Welles seemingly trying to pin down what, exactly, he’s looking at.

A throughline of the conversation is, naturally, movies, and the role of the filmmaker. Hopper frequently refers to filmmaking as “magic,” which Welles attempts to parse: is the director a god, performing miracles, or a magician, manifesting illusions? Watching the film, it’s not difficult to assign the two men roles. Hopper is the magician, laughing and philosophizing and expertly dodging his inquisitor’s questions. Welles, of course, is God, unseen throughout the entire film, that incredible voice booming out of the darkness. In many ways, Hopper and his generation are Welles’ creation; it’s Welles’ task to figure out whether he should be flattered or not.

Welles is clearly both amused and bemused by his subject. Hopper is clearly having a blast holding court before both his followers and his idol, spooling out stoned wisdom and self-mythology. Welles, of course, has a nose for bullshit– he made an entire film about it. Throughout the conversation, Welles attempts to pin down something concrete from the man he describes, with only a whiff of sarcasm, as “the seminal personality of a whole generation”– a political stance, or a unifying principle. Hopper dodges and weaves, cracking jokes and hiding amidst the mumbo-jumbo. Eventually, Welles has heard enough, declaring, “You’re just a sly damn politician running for office.” Hopper has no response, but if his confidence flags, he doesn’t show it.

Yet if Welles is skeptical of whether Hopper has anything to say, he also seems to enjoy his company. Welles is, of course, an old man, out of touch with youth culture (at one point he asks Hopper who Bob Dylan is, and it’s not clear whether he’s joking), but he does seem to feel some kinship with them. “I don’t like the kids because they’re kids,” he muses, “I like the kids because they’ve got fight. I like that they throw bombs. I’m an old-fashioned nihilist.” Hopper, at this point in his career, was as much a self-promoter as he was a filmmaker, but so was Welles when he was the wunderkind extending his brand Hollywood. Even if Welles saw through Hopper, there’s a good chance he saw some of himself in him as well. Game, as they say, recognize game.

Of course, as we know from today’s vantage, Hopper’s career as a director would mirror Welles’ all too closely. Much of the conversation in Hopper/Welles concerns The Last Movie, Hopper’s then-in-progress follow-up to Easy Rider. That film turned out to be a boondoggle, a shaggy, muddled critical and commercial failure which disappeared from theaters quickly and wouldn’t hit home video until 2018. That failure, along with Hopper’s spiraling drug use and instability, made the one-time next-big-thing all but unemployable for the remainder of the decade. Hopper would emerge from the woods in the mid-1980s as an in-demand character actor, but he never regained his mojo as a director; following The Last Movie, he directed only five more features, one of which wound up credited to Alan Smithee.

Which brings us back to that awareness. Could Welles really sniff an imminent flame-out, or was he just a deeply bitter old man? In the end, it doesn’t matter; to the last, Welles was adept at framing his own narrative, and drawing those around him into his orbit. Hopper/Welles is a very simple film (some might argue whether it even constitutes a film), but even consisting as it does of two guys yakking for two hours, it comes off as a cracking bit of entertainment thanks to the two gargantuan personalities on display. Most of what’s said is bullshit, but it’s great bullshit, a “Dueling Banjos” of slightly drunk bravado. Watching Hopper/Welles is like a great conversation at the end of a great party, and I think it’s safe to say that’s something we could all use right now.

Hopper/Welles

2020

dir. Orson Welles

130 min.

Available for digital rental via the New York Film Festival through Saturday, 10/3 – click here to follow our continuing coverage!

Right now Boston’s most beloved theaters need your help to survive. If you have the means, the Hassle strongly recommends making a donation, purchasing a gift card, or becoming a member at the Brattle Theatre, Coolidge Corner Theatre, and/or the Somerville Theatre. Keep film alive, y’all.