As we’ve mused on previously in this space, to become invested in the Boston music scene is often to become an amateur historian. Ours is a history of astoundingly talented musicians who are rightly hailed by scene lifers as heroes, but who are scarcely known outside of city limits. This goes double for venues: while musicians at least often leave a recorded legacy, scores of great Boston rock clubs have vanished into the ether, leaving only a paper trail of flyers and ticket stubs and the hazy memories of those who were there.

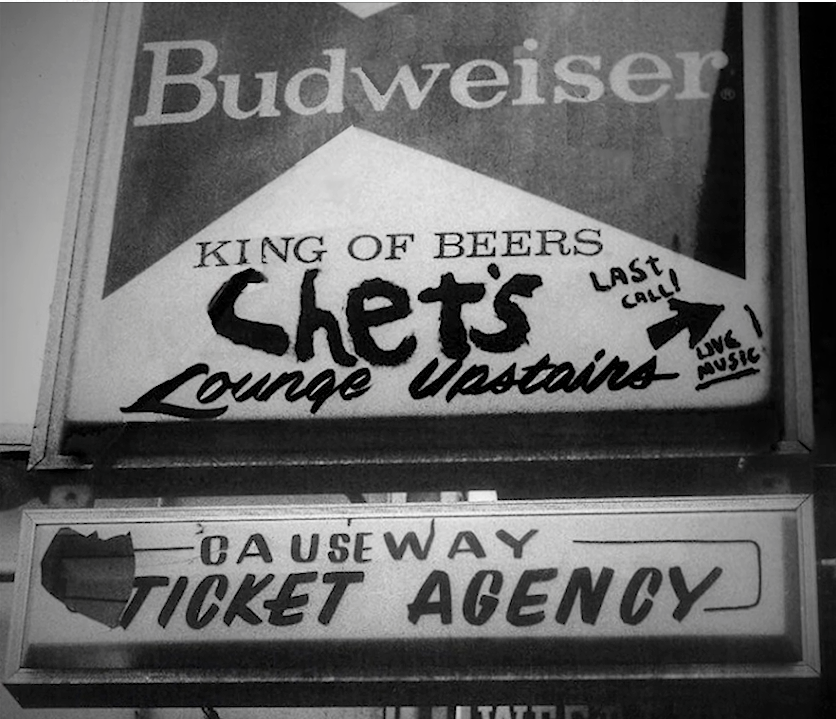

Fortunately, some of the latter have taken it upon themselves to preserve the memory of the hallowed halls that reared them. Such is the case of Bim Skala Bim frontman Dan Vitale, who, along with his brother Ted, has preserved the memory of much-loved North End rock club Chet’s Last Call, as well as its larger than life owner, Richard “Chet” Rooney, in documentary form. The resulting film, Chet’s Last Call: A Story of Rock & Redemption, mixes archival footage, eyewitness interviews, and performances from Chetstock, a memorial concert Vitale organized in 2016. In anticipation of this Friday’s screening at the Somerville, we spoke with Vitale, along with friend and scenemate Sean Brann (of colorful local bands Dogzilla and Archbishop’s Enema Fetish), about Chet, the importance of community, and the hazards of novelty stage props.

BOSTON HASSLE: Just to give some background, I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about the history of Chet’s Last Call.

SEAN BRANN: That’s yours, Dan.

DAN VITALE: Alrighty. It was opened in ‘83, and it closed in ‘87. It was open for almost five years.

SB: Wow, that’s all?

DV: Yeah. We all think it was longer, but it wasn’t! [laughs] One of the things about both of our bands– we got started at Chet’s, and it being a launching pad kind of place, it launched us, you know what I mean? We were able to play bigger clubs within two years of playing Chet’s. And that means something. It really does. Especially in Boston. The Rat might have been a scummy place, but it wasn’t easy to get a gig there! Especially if you had underage people in the band, because they were pretty strict– notoriously mean doormen, you know? They’d fuck with you. And we all tried to make fake IDs and stuff like that.

SB: Yeah, they didn’t want to book Dogzilla, cause they’d had some run-ins with the Archbishop’s Enema Fetish.

DV: Who are in the film as well.

SB: I don’t know if this is a family show you’re taping for, but at that time there were a bunch of tough Southie kids that were doing bouncing at the Rat, and everybody that ran the Rat knew each other, and they could be really mean. And the Archbishops made a mistake of doing a song called “Fuck Me, Jesus.” And then Tim [Halle, the lead singer] got threatened in the stairwell of the Rat by a guy with a knife! [laughs] He wasn’t one of the bouncers, but knew one of the bouncers– they were all friends. And we all had to beat it out of there with our equipment as fast as we could. So after that, it kind of became known– basically, Dogzilla was kind of a sold-out pop version of the Archbishops. You know how, like, there’s a seminal band, and then there’s the boring sold-out one? That was us. So they knew that we were associated with them. So getting in the Rat was really hard. And you couldn’t– you had to have a gig in town. And Chet’s was one of those places that you could just easily get gigs.

DV: If you were selling out Chet’s, or almost selling it out, you could get a gig at the Rat.

SB: Yes. That was it. It’s kind of like the farm leagues for the majors. I mean, it’s all on such a tiny scale, but it was significant to us at the time. You know, we’re in our early twenties. We’d never done anything like this before. Our attitude about that was, “Whoa! I’m in a rock band! This is so amazing!”

DV: The interesting thing about Chet’s was they had protection there, in a really bad neighborhood that no one cared about so much except the mafia people who owned the building. They had a bar downstairs where they advertised that they did passport photos, but I think they also did passports! [laughs] They took numbers. You know, it was a bookie kind of hang-out. But the police hung out there too. So there were gambling policemen there.

SB: Most bands that played Chet’s had at one time or another gone through the wrong door, down on the first floor, had seen a bunch of old guys sitting around a table, playing poker with a lot of cash on the table. And everybody just kind of looks up, you’re obviously in the wrong place–

DV: Then you had to find your way upstairs.

SB: –you take off, and you go up this tiny little stairwell in the back.

DV: But the way that actually worked out in the long run is that they were protected. There were so many police involved downstairs that they made some kind of deal where shitty fake IDs were fine! You know? [laughs] I had one that was made of Scotch tape! It was really cool in that way. We were able to see live music. There weren’t all-ages clubs. We used to rent stages occasionally–

SB: VFW halls.

DV: They still do that! The kids still have to do that, ‘cause there still aren’t enough places for them to play, you know? There’s more, but not enough.

SB: But you could sneak into Chet’s, and the other divey little places… you could sneak if you went in fast enough and they weren’t paying attention.

DV: You had to remember the bar that stayed open a little later than most of the other ones. The other thing about Chet’s was that there wasn’t a strict last call. So part of it– he knew going into it that he would be able to offer people drinks a little after everyone else was locked up. So that was a thing as well. They pushed the curfew because of the protection.

BH: From what I understand, the movie is as much about Chet himself. Could you talk about him at all?

SB: Okay, here’s the thing. Chet– we had some fragments of those guys angry at us about the Archbishops, but Chet thought the Archbishops were the greatest band ever!

DV: Well before he died, he said, “I want them to play at my funeral!”

SB: The only place the Archbishops weren’t banned was Chet’s, and another place in the Fenway called Jumpin’ Jack Flash. In 1988 we played a couple of gigs, and one of our members’ parents ran a pharmaceutical supply company, so he got a couple of crates of enemas. We spent two weekend days dying all the boxes white, dipping them in white paint, and putting them aside to dry, and the next day with a magic marker hand-drawing “Archbishop’s Enemas” on the box. And he’d hand them out at the show, thinking it was kind of a fun thing, you know? It was Tim Halle in a g-string, with cross made out of guitar necks with a frog crucified on it, singing about this religion that he’s made up about a woman who goes shopping in the mall, and we’re handing out enemas. And we thought, “Oh, okay, whatever.” But there were a lot of hardcore kids there. So they don’t think of it as like “Oh, I got a souvenir.” They open the box, and put the little hot water envelope in the thing, and they start squirting each other!

DV: Over everything!

SB: And the Archbishops– we would always twitch on the ground, because it was part of the general craziness. And there was broken glass, and I was like, “Okay, whatever.” We’re just in the fray. So I was bleeding, and with salt water on my cut up back!

DV: Oh, god! [laughs]

SB: I almost couldn’t play, it stung so much! But “playing” is a relative term with the Archbishops anyway..

BH: So what drew you to document all of this in the film?

DV: Well, there’s snippets of many of the bands who played at Chet’s playing again after thirty years. There’s many interviews with band members and bands that are not playing, other people like Dave Minehan [of The Neighborhoods], who we didn’t get actually playing. But we used some old footage of him playing. We use old footage of a lot of the bands. It’s a combination of old footage of the bands and bands performing again at the memorial show. A lot of interviews and stories with the family– sister, brother, people who worked there, bartenders, doormen, sound men, things like that. But the arc of the story, though– it’s so much fun to talk about all the debauchery and stuff, but the arc of the story swings around when Chet just– as his sister says in the film, Chet said, “I’m either gonna die or I gotta go into rehab.” Because he was not only booking all these bands and running a club, but he was dealing drugs, and he was addicted to heroin, and he was drinking way too much. So anyway, the film also documents his coming around. Within a year of rehab he decided to go back to university, he went to Suffolk, and he did whatever it is– two thousand hours of counseling for free– and finally got his counseling license, and counseled addicts and alcoholics for the rest of his life, which was about twenty years. So the arc of the story’s beautiful. He ran a club for five years, helped lots of people… then five years in rehabilitation and going to school, and then twenty years helping people get out of drug addiction and alcoholism. So it’s a pretty cool story.

BH: You mentioned some of the people you interview. What are some of the subjects of the interviews?

DV: There’s a lot of talk about various madness and stories, like Sean was just telling you, of things that went on there, but also a lot about how much it meant for us when we were that young to have somewhere to play, and to have somebody who actually was closer to our age who was a club owner.

SB: Yeah.

DV: And it seemed like he really listened to the local music show every night.

SB: He did. He was listening. And, like, what club owner listens to the music? He actually had opinions on, not what bands were hot, but what bands he liked. And yeah, it’s always fun to talk about the debauchery and all that craziness, but if you had a crazy idea– I was in two other bands I can’t remember their names– you had an interesting idea and you wanted to try it out, you could get Chet to go for it. It wouldn’t be a big night, you know? But also back then in the punk rock scene, you could fill a little club like Chet’s on a Wednesday night… It was a petri dish, man. And it was just such a great thing to have. I don’t know how you create that inorganically. It just kind of happened. But it had a lot to do with Chet, you know? The guy’s actually a fan. And a lot of club owners were just like, “Let me get a lot of college kids in here and sell beer.”

DV: You’d never find a guy who actually enjoyed the music!

SB: Chet was a fan. And if he was still alive today, he could tell you about different bands. “Ohh, I liked it when they did this! And then they tried this stuff, and I didn’t really like that!” He was like that.

DV: Nobody else was like that. No other club owner I met. In other cities there have been, but not that many. I mean, when you think of how many clubs there are… If every city had a Chet, there’d be a lot more music. A lot of kids give up because there’s nowhere to play, they give up because they get one gig at a club and they can’t get another gig after that, or there’s just not enough places to play, so you get tired of just rehearsing. If you can’t get out and play in front of people, the band is just gonna fizzle. And it’s such a great outlet– art in any form– it’s such a great outlet for young kids. It’s so stupid that so many of the clubs are twenty-one-plus.

SB: Only the hardcore scene has all ages shows.

DV: They’re the ones that need it the worst, I think. The more damaged you are, the more you gotta get out to a show and burn some steam off.

BH: Going from that, I don’t know if you’re familiar with Boston Hassle, but a lot of what we do is sort of rooted in the local DIY music scene, and I’m sure that a lot of those people will be the sorts who see the movie when it plays around here. Is there anything that you hope young musicians take away from the movie watching it?

SB: Community. The big deal that was. There is a community in the hardcore scene– I’m so old, you know, I’m fifty-six now, so my friends have kids that are in the hardcore scene, and what I see in that scene is community. They rip off of each other, and say, “I’m gonna try something like this, but I’m gonna change it a little.” That’s what we had back then. We had this community. It’s worth thinking about what it is that makes a scene gel, and makes it come to life, gives it that spark. And one of the things that Chet’s did was help forge a community.

DV: A person like Chet could take on a place where young people could experiment with music. Or poetry. Chet gave people an opportunity to do that on some nights. Or show their films. Or have artwork on the wall. Any number of things like that, that a lot of European community centers or youth centers do, and they’re a lot better at it than America. I think the answer is more youth centers, or more places where music can be experimented with, but in front of people.

SB: It’s hard to make money, though, if you can’t sell booze at a 300% markup.

DV: It is. But the hardcore groove overcomes that in general. All-ages punk rock shows overcome that. Reggae shows, even.

SB: But the bands knowing the bands. What was also cool was, yeah, you see it today, but you see it only within a style. As far as I know. You know, I’m old and out of it. There might be stuff going on that I don’t know. But what was wonderful about that community is I didn’t say, “Oh, Bim Skala Bim, we can’t gig with them, they’re a ska band! We’re a punk band!” There was no thought about that, you know? It was just like, “Oh, yeah! Let’s do a gig! I like you guys!”

DV: It really was.

SB: And again and again, you would go out to a show, and there would be– you can imagine, Bim Skala Bim playing in a show with a death metal band and an emo band– or what passed for emo back then– and a gothy band, and a funk band.

DV: And it might have had something to do with there were so few people doing what we were doing, even though it was different, that we were perfectly comfortable playing together, and it made more sense to play together. Now everybody wants to group genres more together, where we mixed them up like crazy.

SB: And at that time, back in the ancient times, people that didn’t know about the punk world, if they went to see a live band, they were going to see, like, a Journey cover band. Or, you know, a cover band. They didn’t have any idea– maybe a blues rock band. But they didn’t have any idea.

DV: There were more cover bands than original music, certainly.

SB: Yeah. And they didn’t have any idea that, “Whoa, you wrote your own songs? And you’re not famous? What’s gonna make people want to see that?” You know, they were just puzzled. [beat] Anyhow, community. That’s my buzzword.

Chet’s Last Call: A Story of Rock & Redemption

2018

dir. Dan & Ted Vitale

120 min.

Screens Friday, 7/5, 9:00 @ Somerville Theatre – Director in person!

Also screens Thursday, 8/1, 7:00 @ Brattle Theatre

Thanks Oscar, such a fun read!

I have memories of AEF when it was in its infancy. The guitarist Jim was the back bone and Tim was the frontman. Jim……whatever happened to the jazz master?