Valerie Solanas shot Andy Warhol, but she has some “involved reasons” why, as she explains to the police in the beginning of Mary Harron’s film about the real-life assassination attempt. The story is bookended by events after her arrest, punctuated by monologues of Valerie reading excerpts from her manifesto, and mostly told as a flashback to the circumstantial years leading up to the shooting. Through this triptych, we come to understand these “involved reasons,” the complexities and nuances of Valerie Solanas as a character that make the situation not as simple as a mere assassination attempt.

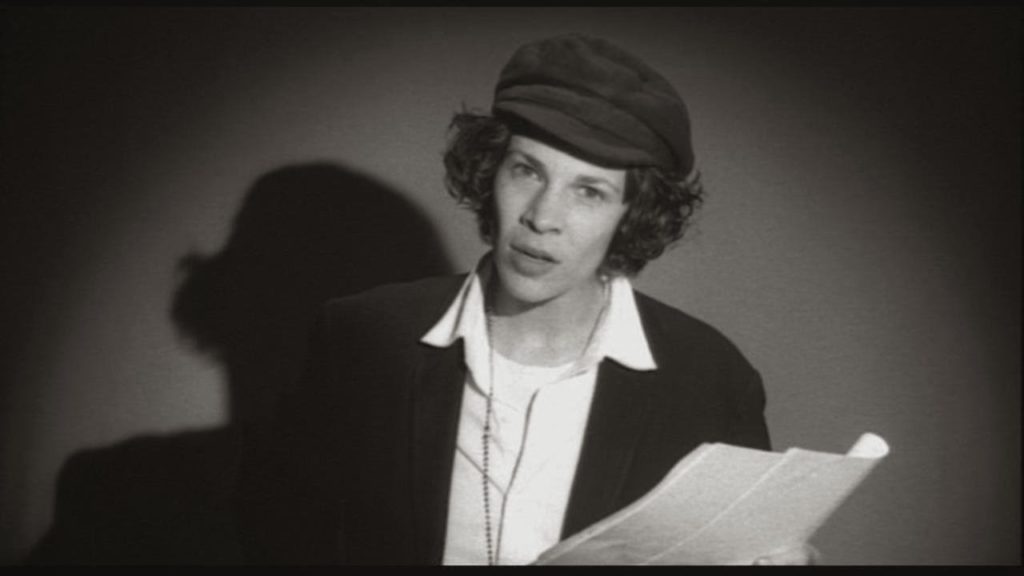

Valerie is the breathing stereotype of a radical feminist: she is a lesbian who hates men. In the SCUM Manifesto (Society for Cutting Up Men), she presents the idea that women are genetically superior to men because the Y gene is an incomplete X gene. She is determined to find a way to reproduce without the involvement of men at all.

Note: She did not shoot Andy Warhol simply because he is a man.

She is an independent, though penniless and virtually homeless, woman. In order to survive and cultivate a lifestyle in which she can write and hold no formal job, she turns tricks for money. She manages to do this and maintain a sense of empowerment: she exploits men’s base animal desires and takes their money.

A chance encounter walking the street leads her to Maurice Girodias, owner of Olympia Press, a publisher of pornographic and erotic novels. He likes her for her frankness and unabashed admission of her occupation. He offers her a book deal and an advance of $500. When she meets him for dinner to sign the contract, we see her wearing a dress and discernible makeup for the only time. And so, again, we watch as she takes advantage of men to get what she needs (namely, money).

In both of these cases, her value lies in her dirtiness and sexuality. Her relationship with Andy does not necessarily differ in this way. They become associated when she gets to him a copy of her screenplay, Up Your Ass, in the hopes that he will produce it. Swayed by the opinion of his sycophants, he dismisses it for its repulsiveness. She keeps asking him to produce it, and he makes excuses not to. What he does do is keep her around: she has a role in one of his movies, he records an impromptu monologue by her. He tells her that she is dirty, and asks her to use that dirtiness. Eventually, she becomes too much for him, and she gets pushed out of the social circle, and that is that.

She did not shoot Andy Warhol because he kicked her out of the In Crowd. To the contrary, she seems to have no interest in the social scene, and wants only for him to produce Up Your Ass, which he never does. He also never returns his copy.

Eventually, Valerie starts to lose it. She looks over her contract with Girodias and realizes that she may have signed over all the rights to her work. Because Andy still has a copy of her play, she develops the idea that they are conspiring against her: they are holding her work, and thus her freedom, hostage in a scheme to make themselves millions.

On the surface, this is why she shoots Andy Warhol. But Harron created a character propelled by motivations far more intricate than that.

The men who paid her for sex exploited her, surely. Girodias exploits her naiveté and poverty, definitely. But she holds no esteem for sex. The exploitation that really matters is the one that looks least like exploitation. Andy Warhol made Valerie Solanas no promises, but he used her in his work and kept her around. His is the only true exploitation, because he was the only one she truly relied on: she needed him to produce her play because she could have no platform without his reputation.

How maddening it must have been for a woman who felt that men are inferior and unnecessary, even for reproduction, to have needed a man to gain a voice.

Valerie is admitted into a mental institution after she shoots Andy Warhol. Though she certainly does slip into conspiratorial delusion and paranoia, this outcome carries political significance all the same. It was a weird experience, being a woman in 2018, watching a movie made in 1996 about something that happened in 1968, and wondering all the while: What has really changed? How crazy was she? How often are women today written off as “crazy” for expressing opinions? Is it insane to believe that two men might plot to take credit for a woman’s work?

In one of her monologues, Valerie delivers what was easily my favorite line in the film: “I’m so female, I’m subversive.” If we understand her assassination attempt as an action in keeping with the ideas she proposes in the SCUM Manifesto, then it was both feminist and subversive. It was also how she ultimately gained the platform that allowed the SCUM Manifesto to become a feminist classic. She achieves a feminist ideal in shedding her ties to the masculine realm, in acting according to her values, in using her voice.

I Shot Andy Warhol

1996

dir. Mary Harron

103 min.

Screens Friday, 3/16, 9:30pm @ Brattle Theatre

Part of the ongoing series: Celebrating Women’s Cinema: The 25th Anniversary of the Boston International Festival of Women’s Cinema

Rare 35mm print!