As a kid, I was always more into the Marx Brothers than the Three Stooges.

When I tell people that, I generally receive one of two reactions: a sly, knowing, “I hear you” nod, or an exasperated, “Oh, HERE we go” eyeroll. The implication, of course– on both sides, really– is that the Stooges are the “normal” choice of the average American male, while the Marxes are the contrarian choice of the intellectual elite. It is perhaps a sign of our hyper-polarized times that one’s preference between nearly-century-old teams of former vaudeville comics can be boiled down to yet another binary of left-vs-right talking points, but I’m willing to bet that, even before you read this paragraph, you had one of those two reactions.

And yet, in a very real way, I can see it. The Three Stooges, of course, were completely apolitical (barring this infamous short, in which Moe Howard became the first American actor to portray Adolf Hitler on film). Yet the old-fashionedness of their films– both in terms of their simplicity and their occasionally unfortunate portrayals of women and people of color– represent a nostalgic vision of America that appeals to Red Staters*. The Marx Brothers, on the other hand, are not so much apolitical as anti-political. Like Bugs Bunny and MAD Magazine, the driving ethos of any given Marx Brothers film is complete and utter disrespect for whatever representative of authority and establishment happens to be present. In Horse Feathers, Groucho summarizes his philosophy in the song “(Whatever It Is) I’m Against It”; it’s certainly no coincidence that punk godfathers the Ramones claimed the sentiment as their own nearly fifty years later.

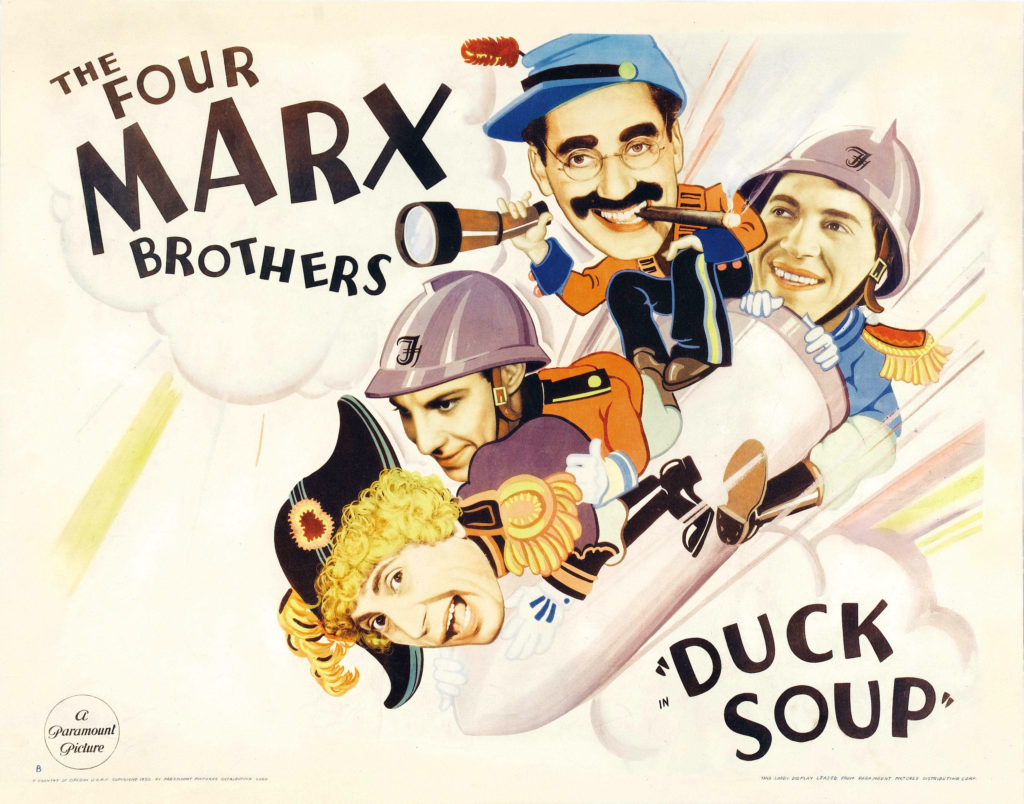

There is perhaps no better example of the Marx Brothers’ anarchy, or of their comedy in general, than 1933’s Duck Soup. On a surface level, Duck Soup can be considered political; Groucho plays Rufus T. Firefly, leader of the tiny nation of Freedonia, which is led into war via the machinations of spies Chicolini (Chico) and Pinky (Harpo). But Duck Soup doesn’t exactly take a stand on any particular issue; rather, its larger point is that war, politics, and espionage (at least as portrayed on film) are really silly. As in their best films, Groucho, Harpo, and Chico are essentially chaos bombs dropped into an otherwise stately premise, running up against authority figures like wealthy dowager Gloria Teasdale (perennial straightwoman Margaret Dumont) and Firefly advisor Bob Roland (Zeppo, whose primary characteristic, as in most Marx films, is “also present”). Most characters outside the main trio exist to either be mocked by Groucho, swindled by Chico, or confused by Harpo. The final scenes are an all-out mockery of the stodgy war films which clog up TCM every holiday weekend, and, arguably, of war itself. This stance would drop dramatically out of fashion a few years after the film’s release, of course, but today it’s what endears the Marxes to generations of weisenheimers– including your author as a small child.

But, of course, to paraphrase the old cliche (which, ironically, has been attributed to just about every master of the one-liner but Groucho Marx), writing about comedy is like dancing about architecture. We appreciate the Marx Brothers’ disrespect for authority– and the Three Stooges’ simplicity– but that’s not why we love them. We love them because they’re fucking funny— and Duck Soup still is, nearly a century on. You don’t need to take a political stance to laugh at Harpo’s mirror routine, or Groucho’s increasingly elaborate costumes in the finale, or even just their respective takes on the eyebrow waggle. Honestly, you can probably just stop reading this and watch the movie. After all, to quote one mush-mouthed con-artist or another, “Who are you gonna believe, me or your own two eyes?”

* – I feel I should point out that I am not saying that all Three Stooges fans are Trump supporters; I honestly do like the Stooges, and will usually land on them when a rerun is on. For that matter, I’m also aware that enjoying just about any comedy before a certain point in American history requires looking past a certain amount of problematic material. Just bear with me while I make my smartypants critic point, okay?

Duck Soup

1933

dir. Leo McCarey

70 min.

Screens Monday, 6/4, 7:00pm @ Coolidge Corner Theatre

Preceded by a seminar with Boston Globe film critic Ty Burr! (Seminar tickets $25 – click here to register)