Also known as the unofficial Asian American photographer laureate, Corky Lee’s name has often been mentioned by AAPI filmmakers that I’ve talked to, whether as a source of inspiration or because they are still reeling from his unexpected death in January 2021. I had no doubt that there was going to be a shot at documenting his legacy, though I didn’t realize at the time how extensive it was. While his decades-long work provide enough historical context as its own film, Photographic Justice weaves in Lee’s life behind the camera.

Suffice to say, this man never stopped working. The picture above was taken in the 1982 protests following the unjust murder of Vincent Chin (also photographed by Lee was a young Helen Zia at the protest, who would soon become one of the biggest advocates for AA rights). Ahead of the documentary’s screening at ArtsEmerson on 10/14, I spoke with director/producers Jennifer Takaki and Linda Lew Woo about one of the most prolific figuress in Asian American history.

The conversation has been edited for brevity and flow.

BOSTON HASSLE: How did you know Corky Lee and how did you decide to film him?

LINDA LEW WOO: I’ve known Corky since 1968, and we’ve had a long friendship.

JENNIFER TAKAKI: I met Corky in 2003, maybe. We were at an event together and I happened to ask him where the bathroom was. He started giving me the history of the building and that led me into asking him who he was. My background is in news and I was intrigued by him, so I decided to follow [the story]. It was going to be a five-minute little video but it ended up being a lot longer.

BH: How did you know that it was going to be a full-length documentary?

JT: I knew that I couldn’t stop filming him because he was so interesting. And then it was another year and another year and by that time, you have so much footage. I did do a five-minute piece, but I felt like it wasn’t worthy of who he was. He’s definitely worthwhile of a feature film. He’s so informative, so charming. There are so many things about him that make him such a good subject matter.

BH: After watching the documentary, I felt like it had a good pace on knowing him as a person as well as what he did for his community and policy advocacy. I wanted to know how much footage you had to run through and slim down.

JT: It’s really important for me to acknowledge Linda Hattendorf, who is the editor of the film. Have you seen The Cats of Mirkitani? It’s about a Japanese American artist who was homeless on the streets and had this magnificent backstory. I felt very strongly that she had the heart to do this film. I didn’t know her at the time, but we both lived in New York and when we did meet, she came on board. I attribute the pacing and the storytelling to Linda. Outside of Corky, Linda is the second most important person in this film.

We’re so fortunate that we have Linda Lew Woo as our producer, George Hirose as our executive producer, Brittany Huie Santiago as our AP. There are so many people on this film and so many that have supported this, both financially and helping with areas to interview or screen. Filmmaking is not a vacuum process. Some of the best films can really show the many voices [outside of it]. We took this film to the community and had a lot of different screenings so that I can get feedback. It’s reflective of the community process and that storytelling. Linda and I were very good about asking people to make sure that we reflected their stories. We’re not from Chinatown. We’re not from New York, we lived in New York. We wanted to make sure it was an accurate reflection of what people thought of Corky, who was so beloved that it was a tall order. Fortunately, the two of us did not take that lightly.

BH: Was it hard for him to be in front of a camera?

JT: He is who he is on and off camera. I think that’s the beauty of him as a subject matter: he never faltered. Everything he said was the way he was. He never changed his train of thought. He never changed his ideas. By the time I met him, he pretty much was to the North Star in his mission to cover AAPIs and get them into media. He was very articulate and always looked good. He never had a “Oh, you can’t film me today, it’s a bad day with my hair, I wasn’t prepared for this.” He was always on, and I think that’s truly exceptional of any person.

BH: The film touches upon this a bit, but what do you think kept him going for all these years?

JT: He was a one-man band to make sure that the community was reflected in the media. That’s what kept him going. He knew what he wanted to do from a very early age and he never stopped doing it. He felt a huge responsibility to the community to make sure that he did what he did.

LLW: Knowing him for so long, that always was his mission. He was very into the community and made it his big cause across the United States.

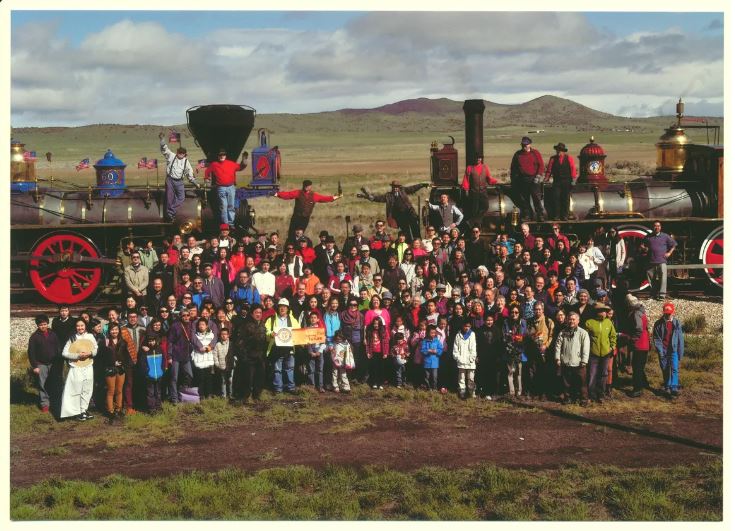

BH: A lot of his work were pictures of these actual moments, but I thought one cool thing that he did was re-enact the Transcontinental Railroad picture in 2014. I was wondering if he ever took other pictures outside of the nonfiction genre.

JT: What’s interesting about that railroad picture is that that’s not the first time he did it. OCA [writer’s note: the organization has rebranded to OCA – Asian Pacific American Advocates in 2013] had given an award and he said that if he’s going to accept the award, he wanted to recreate that railroad photo back in 2002. So he took that photo, which was really the beginning of that mission in the sense that he knew that he would do that photo again. It wasn’t just the Chinese Americans — he wanted to make it an Asian American thing.

Corky also organizes things. He’s not just the guy that they’ll say, “Hey, we organized this, just show up at this time.” Corky was the instigator. He helped with the buses and organized the community. He got the organizations on board and vice versa. That started in 2014, with the significance being the 145th anniversary, and subsequently he did it every year up until the 150th, which would have brought you to 2019. Then, the pandemic happened and I’m not sure what the status of that is, but I’m pretty sure he started a movement where people will continue to go there and [recreate] the Promontory Summit.

BH: Thanks for explaining that. I didn’t realize it was an annual thing.

JT: Yeah, he doesn’t just do things. He really wants to involve everyone and make sure that people like to change these perceptions. Part of that process is doing the same things over and over again. It’s the same reason how every 9/11, he would show an exhibit. He was very adamant about making sure that people saw.

BH: There’s a part at the end of the documentary where he says that there’s still so much that needs to be done. What do you take from that?

JT: He was really good about nurturing the next generation. It was a goal for him to always reach different ages and ethnicities, big cities to small cities. But I also feel like it’s the younger generation that very much embraced him and his ideas. They would see his photos and hear about someone else. It was not only crossing cultural boundaries, but he was also crossing age and ethnic. That’s why the younger population became important. If they read about him in college or if they were doing a thesis, they would hear about him and they’d call him. They’d come around to wherever he was filming and whatever he was doing, sit down with them, talk to them.

You hear a lot of stories, which was one of the most significant things about anyone who dies. I thought I know someone and think I’ve heard it all, but some of those stories came out of the community when he died, which showed the things Corky would do to help different individuals. He shares events by forwarding it to other people, like word of mouth and Facebook. He was always promoting other people and introducing everyone. That last quote about continuing to shoot – Corky was very much about supporting the artists, whether you were a singer or dancer. For photographers specifically, it’s about documenting your own community. He went to one of those events and people had gone to other countries to show their work and Corky’s message to them was, “Shoot your own community.” That was a targeted approach to say: that there’s enough happening in your own neighborhood that you don’t need to look for stories outside.

BH: I really did like that quote about not needing to travel overseas — that you can take the pictures right where you are and still make an impact.

LLW: It would have taken days to show everything that he did, even behind the scenes.

JT: When we’re editing, you think about what makes Corky him. There are moments that we intentionally kept in so that people would resonate with his mission.

BH: Speaking of editing, there was a funny montage that played to a Corky Lee-like theme song. It came off like an old TV show intro. What’s the story behind that?

JT: We were able to use archival footage, whether it was photos, videos, film footage, whatever it was in that case. That song came from the band Slant. One of Corky’s monikers was “It’s tough being Corky Lee.” And I used to say, “You think it’s tough being Corky Lee? It’s tough filming Corky Lee.” He was always on the go.

At the time, Corky’s wife was dying of breast cancer. I believe the band made the song and performed it to help with fundraising [her treatment]. He mentioned the song in one of my interviews and so I hunted the guys down and they were like, “Absolutely, you can use the song.” That’s the thing about the community: everyone was so open to helping out.

Photographic Justice screened at the Emerson Paramount Center on Saturday, October 14 @ 1:30 PM, with a Q&A with director/producer Jennifer Takaki to follow. More information can be found here. The trailer can be viewed here.