Sometimes, and with what seems like increasing frequency, Boston skips the spring. Instead of a gradual, gentle fading of winter which gives way to a delicate resurgence of warmth and vibrance, we tend to jarringly divert from slate-grey slush to smog-heavy humidity. Pools and heaps of filthy snow and ice replaced by mounds of stinking garbage as many leave for the summer, evidently abandoning months of detritus directly outside their one-time residence. The T is delayed and exudes an oppressively close atmosphere of sweat and hot breath. Rent is ever increasing for ever more dilapidated quarters, and university buildings and luxury apartments spring up in every neighborhood. Clubs and venues are phased out to make way for more concept eateries and industrial-chic, garbage boutiques. The planet is visibly decaying and we’re being sold the future of the coal industry. So when the summer brings restless nights of anxiety and heavy storm clouds of dread darken your days, may we all find some strange commiseration. What better validates our existence or makes it more basic and vital than shared experience? These become the objective elements in the stories we tell ourselves in order to live. The narrative arc of consequence and development that we inevitably internalize. So then, who sees what you share? And if this is a concern, how does it affect the telling? Do we make the story more compelling sweating the technique or drawing attention to the conceit and our singular part in it?

Sometimes, and with what seems like increasing frequency, Boston skips the spring. Instead of a gradual, gentle fading of winter which gives way to a delicate resurgence of warmth and vibrance, we tend to jarringly divert from slate-grey slush to smog-heavy humidity. Pools and heaps of filthy snow and ice replaced by mounds of stinking garbage as many leave for the summer, evidently abandoning months of detritus directly outside their one-time residence. The T is delayed and exudes an oppressively close atmosphere of sweat and hot breath. Rent is ever increasing for ever more dilapidated quarters, and university buildings and luxury apartments spring up in every neighborhood. Clubs and venues are phased out to make way for more concept eateries and industrial-chic, garbage boutiques. The planet is visibly decaying and we’re being sold the future of the coal industry. So when the summer brings restless nights of anxiety and heavy storm clouds of dread darken your days, may we all find some strange commiseration. What better validates our existence or makes it more basic and vital than shared experience? These become the objective elements in the stories we tell ourselves in order to live. The narrative arc of consequence and development that we inevitably internalize. So then, who sees what you share? And if this is a concern, how does it affect the telling? Do we make the story more compelling sweating the technique or drawing attention to the conceit and our singular part in it?

That false dichotomy is the poor American’s read of the essential, lasting contribution of the French New Wave. Writing about that critic-led moment is a bit like David Lee Roth’s joke, “Music journalists like Elvis Costello because music journalists look like Elvis Costello.” A new class of film scholars, articulated by François Truffaut, envisioned an unselfconsciously subjective, diaristic mode of art. Film would fulfill its potential as it evolved into an ongoing autobiography, always in process. This initial call, along with the debatable auteur theory, was almost immediately diluted or discarded by every director save Jean-Luc Godard, who once described his films as merely a continuation of his criticism in a new medium. From 1960 to 1967, Godard directed twelve feature films and, in a flourish of knowing autobiography, announced his retirement with Week End (1967). That number alone is remarkable, but combined with the films’ energy and formal versatility they form an astonishing body of work. While he did not stay retired, he would never approach the influence or kinetic nature of his prolific first run. That said, Week End relates to the idealism of the New Wave roughly like Sid Vicious singing “My Way”; it seethes with undeniable cynicism and bitterness, but is not without a rare, insolent beauty, like a rock in a cop’s face.

Week End concerns a couple’s plot to collect inheritance from the woman’s father, prepared to kill him lest they be left out of the will. Both man and wife are each plotting the other’s murder. Immediately, we are dropped into a world of dull and careless brutality. When venturing outside and out of the city the film becomes a slapstick, cartoon inferno. Each encounter with other travelers grows more surreal and ends up in flares of violence dispatched with impatient disregard. There is no considering the world of language, or communicating desire, or the power dynamics inherent in those structures or much to link these people to Godard’s perennial concerns. They are well-dressed goons; consumers as mere reflections of greed through fits of abject desperation. These are not occurring at the limits of survival, but at the first hint of inconvenience. Human grotesques reduced to stomping, biting tantrums.

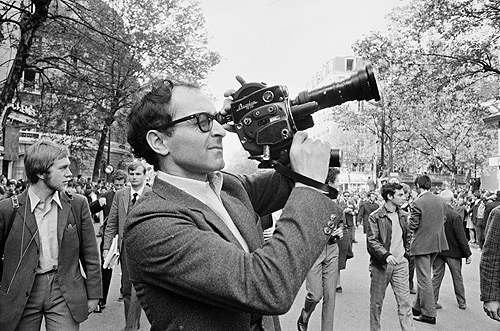

Takin’ it to the streets. May, 1968.

The landscape traversed becomes more hellish with gratuitous, unexplained destruction and human carnage. Dashed entirely are the quiet moments of poetic reflection and celebration of quotidian beauty that served to anchor and elevate 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her (1967), made only months before Week End. The portrayal of humans lacks sympathy. No more are there individual victims trying to assert their humanity in a cacophony of advertising as culture. Gone are the mindful editing replays of scenes to alter perspective and engage environment with curiosity and sublime, albeit brief, fascination. This world is a literal wasteland brimming with garbage that absurdly outpaces the humans casting about for free money. It’s like the outrageous monuments to consumer waste and willful ignorance that choke the streets of Allston every September 1st. Or absurdly narrow-minded energy companies actually blowing up mountains to gouge the last drops of fossil fuel from the planet. Week End portrays unregulated capitalism as a stubborn bully with poor problem solving skills. Where the film finds indirect pathos is an unspoken appeal to self-doubt, to any thinking person who has faced down the vast, willful ignorance of her community and thought, “maybe it’s not worth sustaining.”

Week End was in many ways a not-so-fond farewell to Godard’s 1960s. He was divorced from his wife and frequent collaborator, Anna Karina. He was growing distant from, and more critical of, François Truffaut and the other New Wave class of ’59. His early success and celebrity status were waning, and his recent films were commercially weak. Commercial decline, coupled with his rapid rate of production, made investors wary of his often vague, unscripted concepts. It’s rare and still fascinating that Godard had the awareness and restraint to back away from filmmaking. It’s also still debatable how crazy exactly he became. It’s outrageous that there were ever liberal artists and academics touting Mao’s Cultural Revolution. I feel like Godard’s use of Maoism was more focused, more local. I imagine that he specifically wanted to purge some bourgeois elements in a culture that claimed him but was no longer paying attention to him. And I think based on the work he ended up doing in the ‘70s he clearly wanted to make radical changes to his process. Purely for narrative function the retreat from the public sphere, along with some education work, speaking engagements, collaborative projects and a more hands-on method of video work served as a sort of back to school regrouping. Godard was even involved in a frightening, and fairly secretive motorcycle crash, and shortly thereafter decamped to Switzerland. While he never returned to his pop star spot in culture, he did return to commercial cinema with more meticulously crafted pieces that are sadly underrated. While there are probably better stories, better performances, and better crafted films (Pierrot le Fou) from Godard, Week End may have been his most important.

Week End

1967

dir. Jean-Luc Godard

105 min

Screens Wednesday, 6/28, 7:30PM @ Somerville Theatre

Double feature w/ Riot on Sunset Strip (screening at 9:25)

Part of the ongoing series: Somerville’s Summer of Love

35mm!