I met Artist 9547 a few months ago, introduced by a mutual friend. The three of us nursed beers and spliffs on my back porch, talking lazily about Deleuze’s rhizome, Japanese horror manga, and the weird ways our parents had been acting since the start of COVID. Just three twentywhatevers goin’ through it, as you would.

A few hours into the evening, 9547 mentioned their engagement in the practice of “propaganda art”, and without being able to help myself, I started grilling them. Isn’t propaganda supposed to be a bad thing? Is there a lot of work for propaganda artists these days? More than there used to be? Do you use a graphics program, or do you paint, or do—

Eventually, it dawned on me that I needed to calm the fuck down, so I let it drop. However, before 9547 left for the night, they kindly agreed to an email interview where I could probe the notion of propaganda art to my heart’s content. The results are below.

Though 9547’s line of work is a secretive one—one I imagine is full of clandestine meetings, midnight rallies, and narrow escapes from the pigs—I am extremely grateful for their willingness to give me, and the BH readers, an up-close peek into such a historic art form. If this practice interests you, and you’d like to find the work of more propaganda artists, take to the streets. If you want to become one yourself, same deal.

(The below interview has been edited somewhat for length and clarity.)

BOSTON HASSLE: When did you first start making political art? What were some of the first causes that inspired you?

ARTIST 9547: I first started making political art—for non-public/propaganda purposes—when I was 18, largely to explore intergenerational trauma and as practice exploring ideas in the political theory I was reading at the time. I started making covers for zines and flyers for protests when I was 19, and had just moved to NYC, for police abolition organizations and general anarchist zines my friends were writing at the time.

BH: What does your brainstorming/drafting process look like? Are these works assigned or contracted to you, do you bring them to the groups yourself—essentially, please walk me through the inception of a piece to the finished product.

9547: It’s usually somewhat of a collective process! I often check in with people about what imagery/language they’d prefer (i.e. how blatantly militant? Is it meant for the general public or those “in the know”?) Mostly, I just offer to make stuff when I see it’s needed and when I have time.

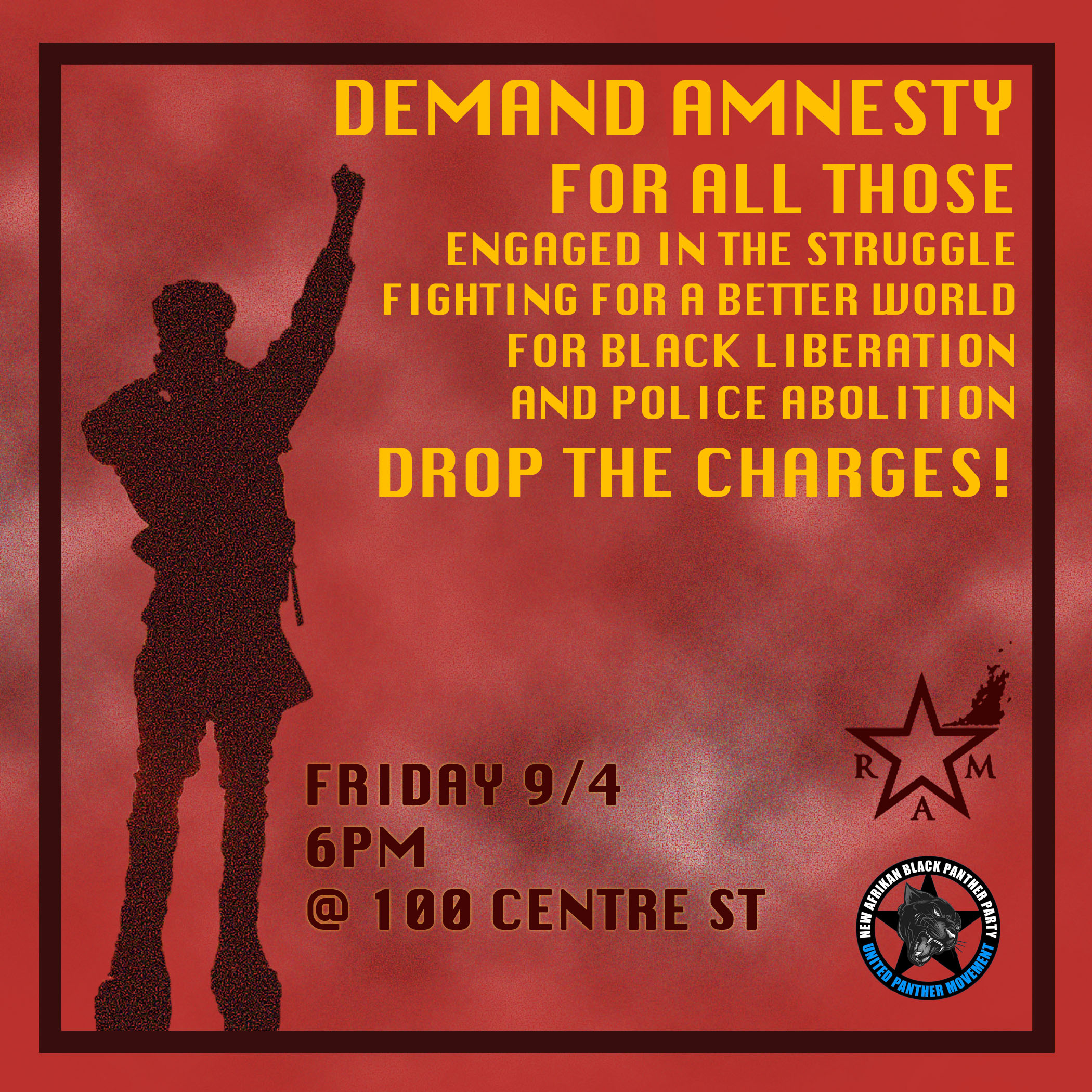

More recently however, I’ve been taking more initiative to bring ideas to people as alternatives to in-person political education. I only really work with people I trust and whose more specific politics are in line with my own. Essentially, if I know there’s an event (protests, movie screenings, teach-ins, etc.), I’ll just offer to make something. Once there’s an agreement on language and general imagery, I tend to pull images from the internet of past events (i.e. if it’s an anniversary protest, I’ll use an image from the initial event), or more symbolic open-source imagery (i.e. if it’s a poster calling to free political prisoners, I’ll use broken handcuffs)… After I make an initial draft, it’s usually sent to a group of people for edits and feedback.

BH: What does the propaganda art community look like? Is it expanding or contracting?

9547: To be totally honest, I’m not sure if there’s much of a community around that specific aspect of organizing! Usually it’s more like, a group of activists has a couple people in the mix they can depend on for art stuff. I think this is also partially due to the necessity of anonymity— we don’t always want to be publicly associated with certain events or groups or ideas.

In Brooklyn specifically, there has been a large influx of more radically-minded political posters since the beginning of the George Floyd uprisings, so even if we aren’t all connected, it’s definitely expanding. The city currently also doesn’t have the budget to clean up “vandalism” right now, so there’s also a possibility things are lasting longer and therefore more visible.

BH: Have you noticed aesthetic differences in propaganda art based on the cause and/or political alignment in question?

9547: There’s definitely somewhat of a difference between anarchist and non-party propaganda compared to that made by Marxist-Leninist parties. I think the culture of more online (specifically Instagram) propaganda varies from the stuff you’ll see IRL as well. I don’t know if I want to extrapolate too much on that, but in short, with regards to online stuff, I feel respectability politics seeps into the aesthetic choices often, and ML party propaganda tends to look like most party propaganda (like Democrats or Republicans), just Communist. I don’t know if I see differences between specific issues though except for maybe Indigenous issues in North America—and I personally wonder about this specifically because I worry about creating one specific image/aesthetic of Indigenousness and what that implies, especially with regards to the US-centrism, colonial paradigms of history and thinking, imperialism, and internationalism.

BH: What, in your estimation, makes for an effective political image?

9547: For most things, I think playing off of history and our predecessors is important! Things like the Black power fist tend to resonate and have an agreed upon meaning. It really depends on who you’re trying to reach out to. If you’re trying to change minds, focusing more on non-alienating (yet politically honest) rhetoric, or more neutral-Left imagery is your best bet.

If you’re trying to reach out to specific people, then using specific imagery towards those causes/politics is important. For example, I never use the anarchy A unless it’s something specifically for anarchists, and I never use it for protests either, in order to avoid attracting unwanted attention, given today’s political climate.

Language that’s both honest to the cause while also being mindful of your audience is crucial as well (if you’re trying to attract newcomers, then the language cannot be too niche or alienating). Color is also important. Neutral colors tend to be good, regardless, assuming the right images/text pops. For example, I probably won’t use the color blue for abolitionist stuff (or any patriotic color combinations). And obviously, considering general design theory is important, too. People’s eyes should go immediately towards the most important image/statement of the work .

BH: What sorts of images characterize the aesthetics of our current political climate?

9547: Since the beginning of the George Floyd uprisings, I’ve definitely noticed a very specific aesthetic for online stuff. Like designs that look like they could potentially be for a noise show or something. This isn’t really bad, I think it’s largely influenced by formerly non-“active in the streets” artist types doing their part now. There is also this more “clean” sort of template I’ve noticed that I do have more criticisms of. However, printed things don’t seem to have changed that much, and often range from more classic designs (kind of retro, if you know what I mean) to designs that almost emulate artsy/hip streetwear (which may be more specific to NYC).

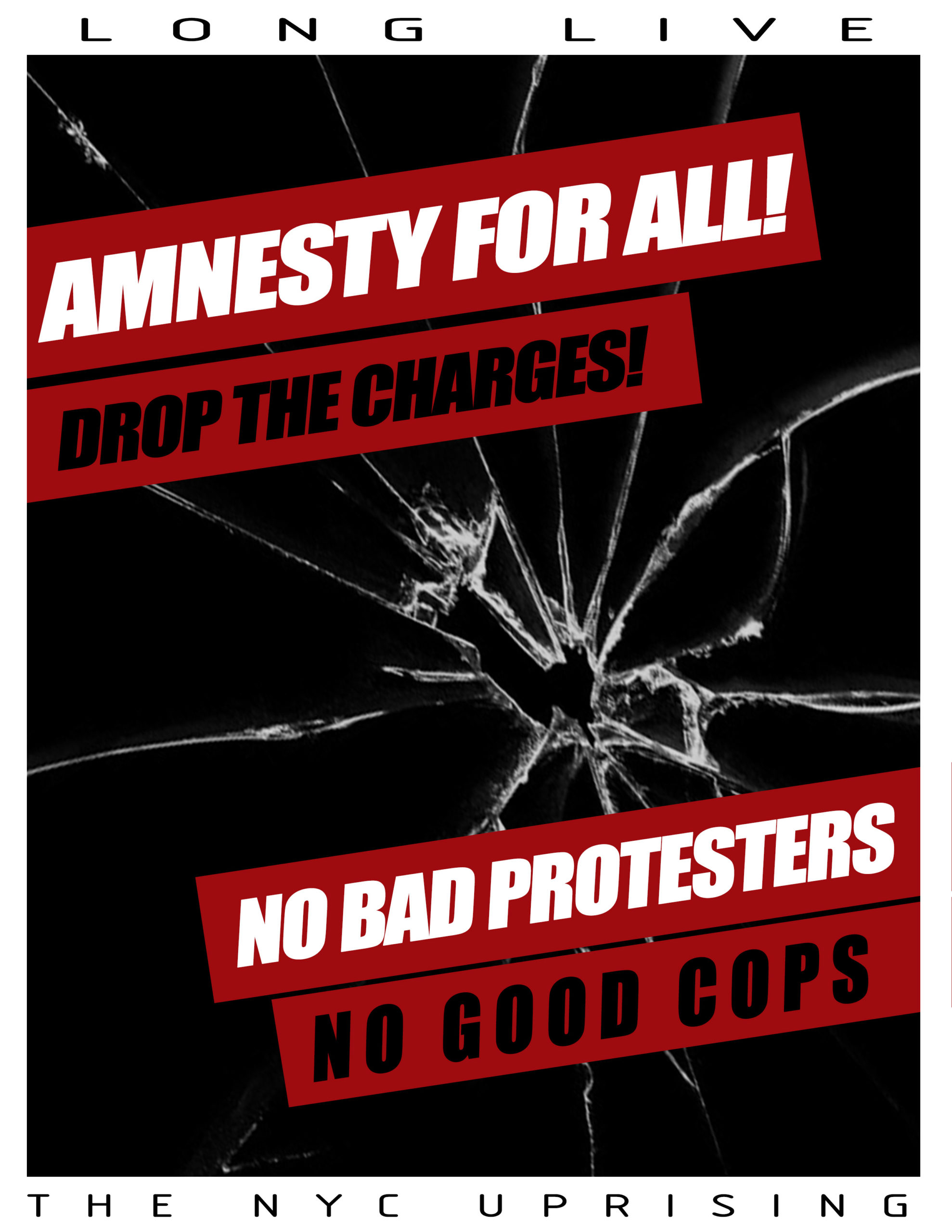

I do see an uptick of more blatantly militant imagery though—the burning 3rd precinct in Minneapolis is unforgettable, or this summer’s burning of NYPD cop cars. Guillotines and severed pig heads have also made a comeback the past couple years! Although in general, I don’t think much is new—we are dealing with a lot of the same core struggles we always have been, so there’s that history imbued in each political image.

BH: Has your work drawn on other political artistic movements of the past? Are there certain tropes you want to reference, or consciously avoid?

9547: Yes and no. Design-wise, I’m definitely influenced by some stuff from the ‘60s, and specifically anarchist stuff of the ‘90s (without being too corny). However, promotional stuff is interesting. Anarchist organizers are always trying to be more militant or better organized than whatever the last big thing was, so I tend to try and come up with designs that distance ourselves from whatever didn’t work previously, while still using recognizable imagery.

BH: What’s next for you, in terms of propaganda art projects? Is there anything major in the works?

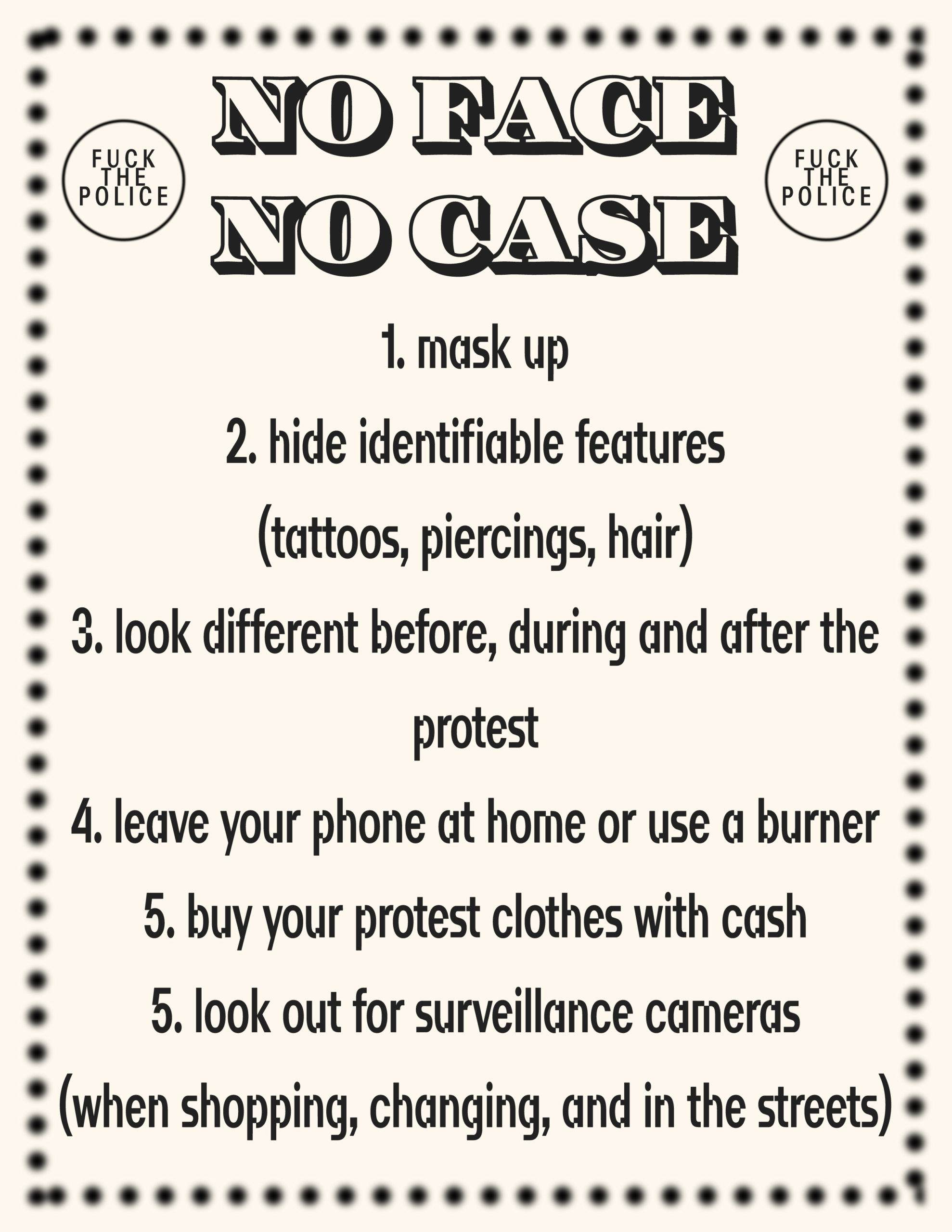

9547: Currently, I’m experimenting with how to educate the public on more intricate aspects of street organizing and mass movements in a time of increased political repression. Like, how do I teach people cyber-security, street tactics, or counter-surveillance in one poster? Due to risk of infiltration, the pandemic making in-person skill-sharing hard, and the need to radicalize the general public to meet political goals, I think public art and propaganda is incredibly important right now. There’s a lot of good info being disseminated online, but not everyone is online or engaging with the same online social circles that younger generations of activists are. My main goal right now is trying to propagate important strategies and tactics—especially anti-repression info—to those who wouldn’t otherwise be in the milieus to receive that information, and to make those practices commonplace.

Due to the nature of Artist 9547’s work, the Boston Hassle cannot provide links to their personal portfolio, nor can we reveal the specific organizations with which they collaborate. Instead, 9547 has provided us with a few national organizations that they believe are worthy of our readers’ time and support: