Historical documentaries are often as interesting for what they say about the times in which they were made as they are for their actual subjects. In trying to bring the past to life for a contemporary generation, filmmakers– good ones, anyway– will highlight elements of a story that they sense will resonate with their audience. A documentary about World War II made in the ‘60s, for example, will likely be very different from one made today, even as they both present the same basic facts. On a strictly formal level, Lisa Cortés’ new rockumentary Little Richard: I Am Everything doesn’t vary wildly from the classic ‘90s VH1 Behind the Music format; there are talking-head interviews with band members and famous fans, archival clips of performance footage and award show acceptance speeches, and a healthy amount of classic singles played over close-ups of spinning records. But the way it frames its subject– a Black, queer, handicapped musician who towers over 20th century popular culture– is both distinctly modern and refreshingly frank.

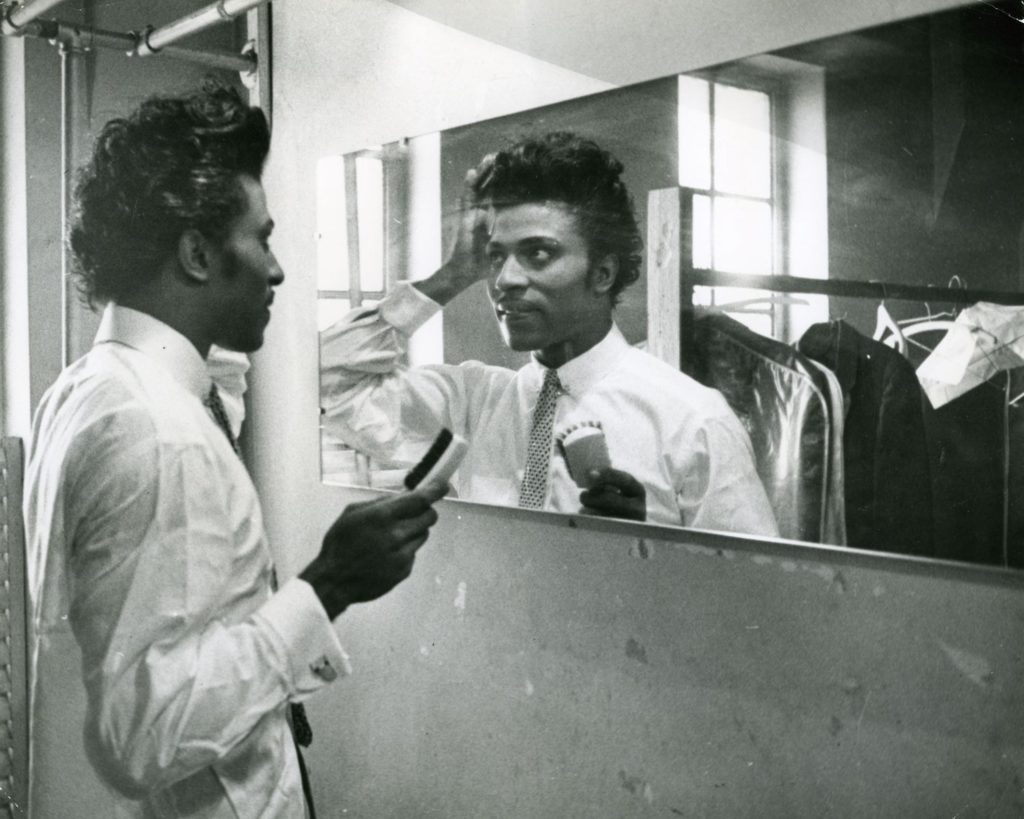

Born the son of a preacher in Georgia in 1932, Richard Wayne Pettiman (dubbed “Little Richard” for his lithe frame) cut a striking figure on the so-called “Chitlin Circuit” of Black-owned nightclubs: flamboyant and pompadoured, with a voice that sounded like it was tearing its way out of his body and a double-speed, jackhammer style of boogie-woogie piano. Richard’s maniacal delivery and stage presence proved hugely influential, particularly among nascent British groups like the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. But influence doesn’t always equal financial success; his own records were often overshadowed commercially, and certainly on the airwaves, by sanitized covers from the whitebread likes of Pat Boone. As the years went on, Little Richard’s career hit peaks and valleys, complicated by alternating excursions into devout Christianity and hardcore drug use. Even into his waning years, however, Little Richard was an arresting presence both on stage and as a regular late-night talk show guest; when he opened his mouth, it was easy to remember why he was dubbed “The Architect of Rock & Roll.”

The above are your standard rock-doc facts of the case, and they are dutifully reported here for audiences who missed him the first (or second or third) time around. But Cortés delves into aspects of Little Richard’s persona which were long relegated to subtext by the rock ‘n’ roll establishment, but which today make him feel more fresh and relevant than many of his contemporaries. Simply put, Little Richard was about as openly queer as a public figure could be in the 1950s. In early performances on the Chitlin Circuit, Richard would often appear in drag as “Princess LaVonne,” frequently sharing a bill with trans pioneer Sir Lady Java (who is interviewed). His breakout hit, “Tutti Frutti,” was by all accounts conceived as an explicit ode to anal sex. In interviews, Richard gleefully describes how his Blackness and his queerness would essentially cancel each other out in the eyes of white audiences, allowing him to traverse spaces which would otherwise have been inaccessible. Interview subjects like Billy Porter and John Waters (the latter of whom adopted his signature pencil mustache in homage to the singer) recount how seeing Little Richard at a young age provided a form of representation which they simply couldn’t find anywhere else. Long considered an “uncomfortable truth” of his legacy, Little Richard’s ambiguous sexuality and gender performance now represent his greatest claim toward contemporary relevance.

Of course, time makes problematic faves of us all, and it is perhaps inevitable that equally uncomfortable truths would arise in their place. Haunted by his religious upbringing, Little Richard would periodically retreat both from rock & roll (if not from the spotlight; with typical immodesty, he immediately dubbed himself “The King of the Gospel Singers”) and from his own sexuality. Depending on the day, Little Richard might present himself as a blithely queer libertine or as a buttoned-down “ex-gay” Evangelical– often within the same publicity tour. In a particularly cringe-worthy clip (deployed twice within the film), Little Richard trots out the old “not Adam and Steve” line to a clearly uncomfortable David Letterman, and the latest images we see of the singer are as a depressingly square figure shilling in prayer for televangelists and other right-wing conmen. Aging gracefully is a difficult feat for rock gods, but Richard’s latter days are more dispiriting than most. As one interview subject says, “Little Richard did an amazing job of liberating others. He was not as good at liberating himself.”

Cortés takes the opportunity to both recount Little Richard’s extraordinary life and work, and to examine what he “means” in a socio-cultural context. While the narrative around rock ‘n’ roll has long centered on such white, straight-presenting artists as Elvis and the Beatles, it represented at its core an intrusion of Black rhythms and sexual liberation into Eisenhower’s Leave It to Beaver America, and few performers illustrated this as explicitly as Little Richard. Refreshingly, many of the interview subjects are academics, both musicologists (who go a long way toward contextualizing Richard’s music both within what came before and after) and experts in the fields of race, sexuality, and gender. It is clear that these professors have spent years of their lives analyzing Little Richard’s music and identity, and there is little doubt that they will continue to; there is, as the kids say, a lot to unpack.

As in many modern rockumentaries, Cortés attempts to break up the talking-head format with stylistic flourishes which don’t always work; a running motif of digitally inserted “stardust” feels instantly dated, and a handful of performances by contemporary musicians don’t gel quite as well as they might (there is also a frustrating amount of unattributed footage representing Richard’s early years, and it’s often unclear whether we’re actually looking at Little Richard and his family or simply period-appropriate stock footage). But I Am Everything is at its best when it tweaks its formula in more subtle ways, using the interview format to reexamine and interrogate rock ‘n’ roll orthodoxy. Most importantly, it succeeds in the ultimate aim of any music documentary: it manages to make 70-year-old recordings you’ve been hearing your entire life sound as fresh, exciting, and dangerous as the day they were laid down on wax. In 30 years, someone may make another film about Little Richard, and it may find an entirely different tone and angle to connect with audiences of the 2050s. As it stands, I Am Everything is a perfect recontextualization for the listeners of today. A wop bop a loo bop, a good goddamn.

Little Richard: I Am Everything

2023

dir. Lisa Cortés

101 min.

Opens Friday, 4/21 @ Coolidge Corner Theatre