Blonde is a Marilyn Monroe story. It’s not The Marilyn Monroe Story.

This is the first point of contention surrounding the new film by Andrew Dominik, but it is far from the last. Though Blonde appears, at first blush, to be a prestigious biopic, it is in no way the latter; rather, it is an adaptation of the 2000 novel of the same name by Joyce Carol Oates, which weaves real events and people from the doomed starlet’s life with healthy doses of speculation, interpretation, and outright fiction. And while it is superficially prestigious– it looks great, and both cast and crew come with considerable pedigree– this is far from some cuddly, Judy-style hagiography. On the contrary, Blonde is an adults-only horror story, positioning its subject as a sort of pin-up martyr suffering extraordinarily for the sins of the twentieth century id. In other words, maybe pick a different Sunday matinee to treat your grandmother to at the Kendall.

Blonde opens with its version of Norma Jeane Mortensen as a child (played by wide-eyed Lily Fisher) living in a squalid apartment with her mother, Gladys (Julianne Nicholson), her only sources of comfort a ratty stuffed tiger and a faded photograph of her father (who her mother swears up and down was an unnamed Hollywood bigwig). When Gladys suffers a violent breakdown, Norma Jeane is sent to live in an orphanage, the first in a long series of betrayals and indignities. We then jump forward to the newly christened Marilyn Monroe (Ana de Armas), a struggling model and actress embarking on a crash course in the seamier side of Tinseltown. On her way to the top (and back down), Marilyn endures a series of fitfully rewarding relationships: a polyamorous throupling with Hollywood scions Charlie Chaplin, Jr. and Edward G. Robinson, Jr. (Xavier Samuel and Evan Wiliams); an abusive marriage to Joe DiMaggio (Bobby Cannavale); a second marriage to playwright Arthur Miller (Adrian Brody) marred by depression and addiction; a tryst with President John F. Kennedy (Caspar Phillipson, reprising his role from Jackie) which can only be described as “really fucking gross.” Carrying Marilyn through these trying times are her dreams– to become a respected actress, to have a baby, to finally meet her long-absent father– but, as anyone with the slightest grasp of the real Marilyn’s life could tell you, dreams can only go so far.

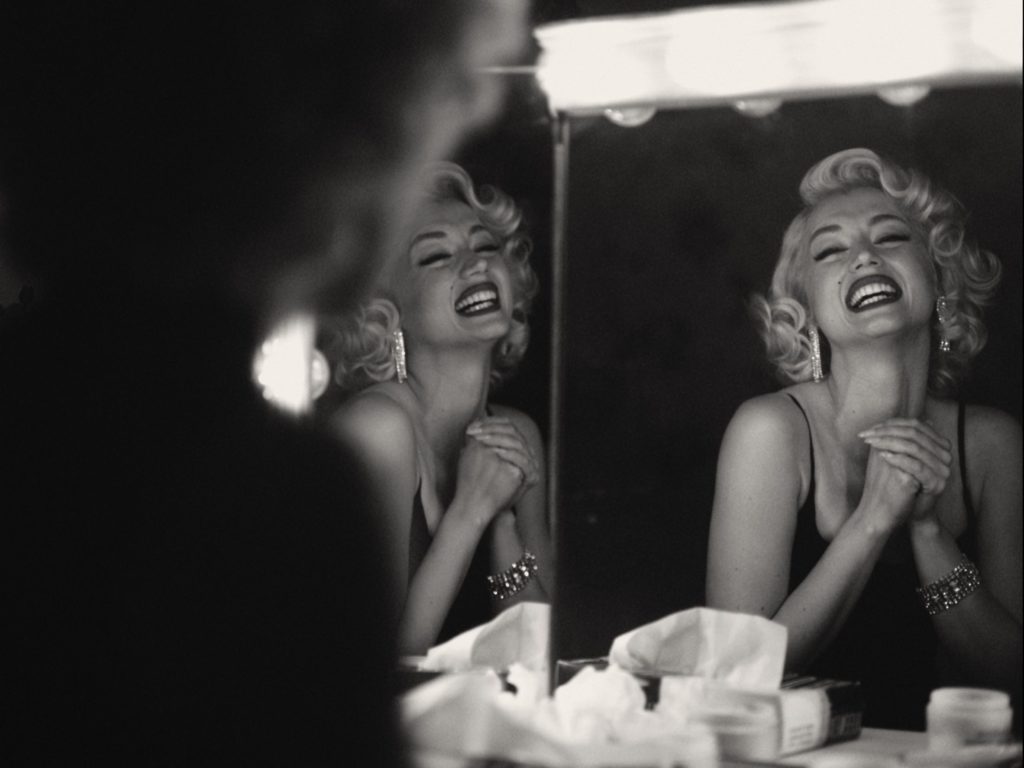

To be sure, Blonde contains elements of greatness. De Armas, for one thing, is fantastic, embodying Marilyn’s innocence and heartbreak and melding her own distinctive beauty into Monroe’s almost seamlessly (de Armas’ native Cuban accent does tend to slip in from time to time, but in a film about layers of artifice it almost feels like a metatextual boon). Brody is quite good as well, playing Miller as a relatively kind man who enters Marilyn’s life at a point too late to do any good. Dominik and cinematographer Chayse Irvin fill the screen with unforgettable images; take, for example, a scene in which the paparazzi’s mouths subtly distort into ghoulish chasms, or a shot of a bereft Marilyn completely alone in a sea of smiling faces watching her signature scene in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. And the score, by alt-rockers Nick Cave and Warren Ellis (marking Dominik’s fourth collaboration with the pair, and second this year), is something of a warbly, avant garde masterpiece, constantly surprising and turning the conventional Hollywood score on its head.

But my god, I cannot imagine the human being to whom I would recommend Blonde. At nearly three hours, the film becomes something of an endurance test. Blonde is so aggressively lurid and unremittingly bleak that one becomes numb to her anguish. Dominik is clearly inspired by Carl Theodor Dreyer’s emotionally devastating 1928 masterpiece The Passion of Joan of Arc, but that film benefited from the dreamy surrealism inherent to the silent screen. Blonde, on the other hand, is weighed down by frequently stilted dialogue (Oates is a capital-G Great Writer, but her work is very much written for the page). The result is oppressive and repetitive, and nobody’s idea of a good time.

As is so often the case these days, Blonde has been the subject of heated debate since well before its first public screening, with critics questioning the ethics of filming an explicit, NC-17-rated film about a subject who is no longer around to speak for herself. While I find these cycles of discourse increasingly tedious, and the pros and cons of input from a film’s subject is a topic for debate (to say nothing of the public equivalence between the NC-17 rating and pornography), but there is something undeniably queasy about Blonde’s treatment of its central character. Dominik is ostensibly trying to show us the tortured woman behind the effervescent face on the silver screen, but at this point the tragedy of Marilyn Monroe is as well-known as the public image, and the version we see here essentially trades one superficial reading for another. We see Marilyn in acting classes with Lee Strasberg, but we see little of what drives her toward greatness; later, when Monroe startles Miller with a keen insight into his work, it comes as just as much of a surprise to the audience. The portrayal lacks humanity; Sad Marilyn feels like just as much of a flattened facade as Sexy Marilyn.

Then there’s the subplot involving Marilyn’s dreams of pregnancy. Marilyn conceives three times over the course of the film, once ending in miscarriage (which is true) and twice in abortion (often rumored, but never proven, and not borne out by her autopsy). Each pregnancy is announced by the sound of a beating heart, accompanied by a writhing CGI fetus; the abortions are shot like a horror movie, and contain what may very well be the first use of fetus-eye-view camera in a mainstream drama. Blonde was shot largely in 2019 (its completion and release delayed by the COVID-19 shutdown), so it may simply be a case of poor timing, but it is impossible to watch these scenes without thinking of the horrific right-wing propaganda which this year led to the repeal of Roe v. Wade. And even if this storyline was not included as anti-choice rhetoric (Monroe did, by all accounts, desperately want to be a mother), a scene in which Monroe’s unborn fetus talks to her and asks her why she killed it can hardly help but come off as camp. It’s never a good sign when your dramatic film can be unfavorably compared to an infamous Christian ventriloquist record.

I will give Blonde credit for not taking the easy way out. There are any number of facile, crowd-pleasing films about Marilyn Monroe which can be (and have been) made, and Blonde isn’t any of them. But the film goes so far in the opposite direction to be often nearly unwatchable. The gauntlet through which Blonde runs its heroine is brutal, arguably misogynist, and indisputably unpleasant. “I always get the fuzzy end of the lollipop,” Monroe’s Sugar Kane famously quips in Some Like It Hot. In Blonde, Dominik seems determined to shove the fuzzy end down the audience’s throat until we gag.

Blonde

2022

dir. Andrew Dominik

166 min.

Streaming Wednesday, 9/28 on Netflix

Now playing at Kendall Square Cinema