As I prepare to describe the plot of After Yang, the new film from Columbus director Kogonada, I feel I need to make a clarification: this is not a silly film. On paper, its plot is probably going to sound outlandish, like an episode of Black Mirror (or possibly The Jetsons). But while After Yang does have a satirical edge (and does feature a hilariously over-the-top opening dance sequence), this is not a quirky vision of the future in the vein of this year’s Bigbug. Rather, Kogonada uses his high-tech premise to craft a soulful, intimate portrait of the human condition– whatever that is.

Set at an indeterminate point in the future (we catch glimpses of a space-age skyline, but the homes appear to be contemporary upper-middle-class), After Yang tells the story of a sort of postmodern nuclear family: father Jake (Colin Farrell, also opening today in a drastically different role), wife Kyra (Jodie Turner-Smith), adopted daughter Mika (Malea Emma Tjandrawidjaja), and Yang (Justin H. Min), a “techno-sapien” cyborg purchased as a companion/live-in educator for Mika. One night, Yang malfunctions, and the family finds their options limited: his warranty is void because he was purchased secondhand, the shop where Jake bought him is long gone, and a conspiracy-minded independent repairman is more interested in harvesting him for parts than bringing him back online. As a last resort, Jake brings Yang to a cyborg museum, where the resident curator (Sarita Choudhury) makes a remarkable discovery in Yang’s firmware: a spyware chip which records a few seconds of memory per day, seemingly at random (though the techno-sapiens are the product of a company called “Brothers and Sisters, Incorporated,” there appears to be a good deal of uncertainty among the human population about how they actually work).

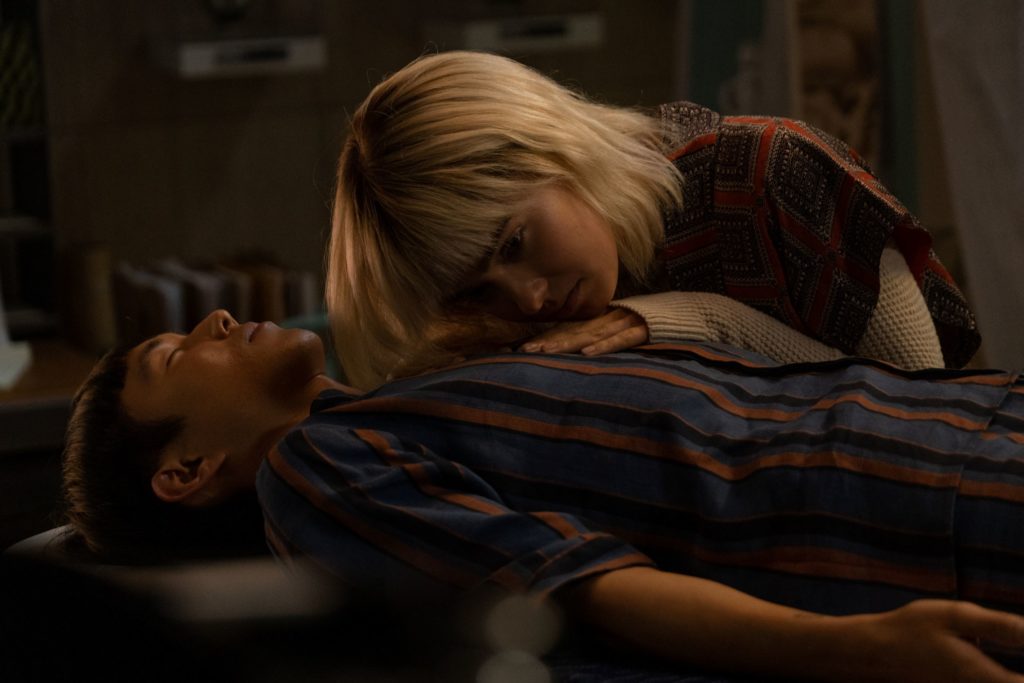

With hopes of resuscitation (or reactivation) fading, Jake begins probing Yang’s memories (in a nifty couplet of visuals, Jake accesses the chip by donning a pair of small, chic sunglasses, while the interior of Yang’s storage is visualized as a thousand points of light surrounding a luminous forest). The memories are at first innocuous– brief, Vine-like snippets of the family around their home– but the deeper Jake goes into Yang’s interior life, the more he begins to comprehend that he was much more than just a machine. He also catches many glimpses of a young barista named Ada (Haley Lu Richardson), who he’s never seen before, but who may have known Yang better than anyone. With the organic material in Yang’s chassis on the verge of decay, Jake must decide what to do with this information, and how to do right by Yang.

Despite a relatively simple sci-fi premise, Kogonada touches on a remarkably wide array of heavy topics in Yang’s relatively lean running time. Most obviously, of course, this is a story about grief. Prior to the accident, it’s clear that Jake and Kyra think of Yang first and foremost as a convenience, albeit a pleasant one to have around– somewhere between a family dog and a Leapfrog tablet. They fail to consider what, exactly, he represents to Mika; though she knows as well as they do that Yang isn’t “real,” he seems to be a much more grounding presence in her life than her parents, simultaneously a best friend, an older brother, and a link to her heritage (as an “Asian” model, he comes pre-loaded with “Chinese Fun Facts”). They also don’t realize until it’s too late what he’s been for them: a sympathetic ear, an engaged student, an all-around warm presence. Early in the film, Jake refers to him by his model number, but as the story goes on, Yang gradually shifts to “my son.”

Needless to say, the presence of a subservient, synthetic Chinese man also raises questions of class and race. In addition to cyborgs, human clones are commonplace in this world, from the young “daughters” of the chummy next door neighbor (played by the always-welcome Clifton Collins, Jr.) to Ada, Yang’s secret love. Jake views clones with a vitriolic level of suspicion and contempt (the neighbor girls know not to spend a second more with him than they need to), but he begins to soften as he spends time with Ada. When he asks her if Yang ever wished he was human, she bitterly spits back, “That’s a very human thing to say.” After some contemplation, she reflects that he did sometimes question “what makes someone Asian.” (Richardson, playing the one character who knew Yang as a human first and an android second, gives perhaps the most affecting performance in a film full of them). Yang had to navigate the world as several minorities at once with good humor, and even though that good humor was likely hardwired into his OS, it’s still tough not to admire his grace.

As a director, Kogonada eschews the clinical, post-Ikea aesthetic that often serves as shorthand for “the future.” Instead, he shoots his locations in warm, dreamy tones, bathed in solar flare and backed with washes of ambient music (the film features an original score by composer Aska Matsumiya, with a central theme by art-rock legend Ryuichi Sakamoto and original song by Mitski). This is a dystopia, but it’s a dystopia of the heart and mind first and foremost. When Jake accesses Yang’s memories, he watches them as cold, hard data files (because they’re so short, he often replays them a few times), but flashbacks from the humans’ perspectives are more subjective: these repeat as well, but Kogonada layers alternate takes, from different angles, with differing intonations of the lines. Memory isn’t simply a recording, but our interpretation of the past, and Yang’s death causes Jake and Kyra to reconsider their own narratives. Even Yang, ostensibly a machine with an internal camera unit, has stitched his memories into a deeply personal quilt. “Random Access Memory,” it turns out, is something more than technological.

But, of course, the technological aspect is impossible to ignore. Like any good sci-fi parable, there is an undercurrent of timely dread which, while obviously exaggerated, feels all too plausible. There is a sense of dark comedy as Jake drags the lifeless Yang from one shop to another, only to be told that his warranty has expired, and older models are no longer serviced, and anyway it’s illegal to open up his blackbox without the express permission of Brothers and Sisters, Inc. (oh, and that will be $250 for the diagnostic check). Obviously there’s a difference between trying to repair a busted iPhone and fighting for the life of an ailing loved one, but it’s easy to compartmentalize how much of our personal and private selves are being delegated to gigantic, uncaring corporations. The world these characters live in is recognizably our own, with technology even more seamlessly integrated into day-to-day life; viewers not attuned to backgrounds and aspect ratios may not even notice that some conversations between characters are actually video calls. Technology makes our lives easier right up until it becomes unprofitable to do so, and when the terms and conditions change, there’s nothing we can do but adapt and relinquish.

I still have an iPod Classic from 2009, filled with beloved playlists and music which will never be on Spotify, which I will listen to until its dying breath. I have an ancient flip-phone which I will never throw away because it contains irretrievable pictures of my late cat. I have friends who now exist solely as Facebook pages; scroll down far enough, past the wall of memorial posts, and I can still see them in the present tense, blithely sharing memes and posting blurry pictures from long-forgotten parties. These are all bits of my life which are, to one extent or another, tethered to dying tech or trapped in a cloud of uncertainty. The case of Yang is obviously an extreme– an entire person, with a whole life full of experiences and loves, lost to planned obsolescence– but anyone who’s ever battled with increasingly ubiquitous tech will surely relate. After Yang is a gorgeous film which will make you want to call your loved ones– and maybe to ditch iPhoto too.

After Yang

2022

dir. Kogonada

96 min.

Opens Friday, 3/4 @ Coolidge Corner Theatre and Kendall Square Cinema, and streaming on Showtime.