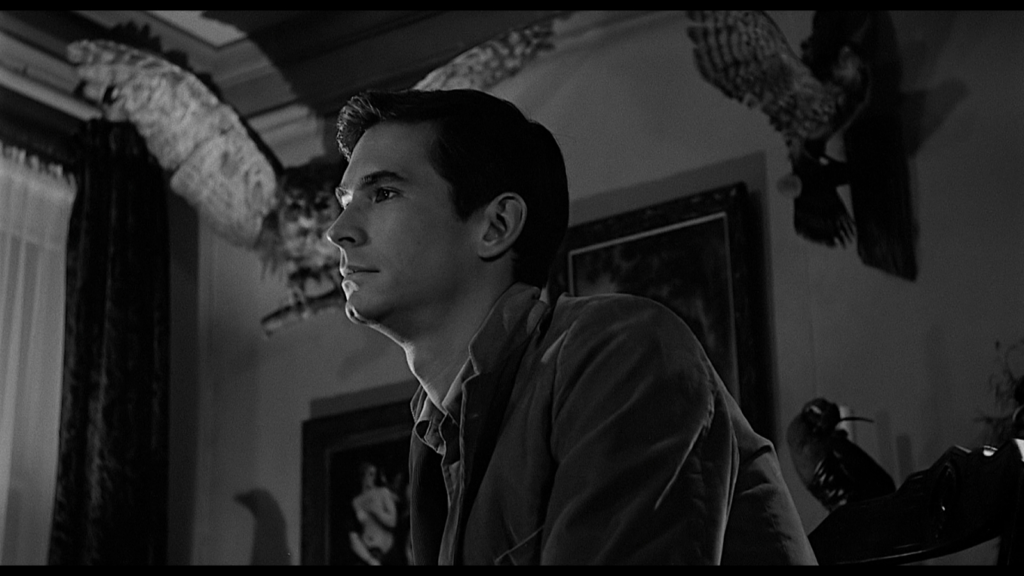

Even the first time you see it, even if you have no idea what’s in store, there’s something unsettling in the way Norman Bates says that a boy’s best friend is his mother. Bates, twitchily portrayed by Anthony Perkins, is goofily underdeveloped, but we can sort of sense the sinister undercurrent of an adult who reduces complex situations through a child’s understanding; nobody knew self care could be so complicated. The Oedipal aspect is kind of unavoidable, and furthers my belief that Freud has really done more for genre fiction that our better understanding of human behavior. Primal perversions, rooted in childhood trauma, are a real godsend to third act exposition, and nowhere is this device dispatched with more gleeful absurdity than in the deus-ex-wackjob coda to Psycho (1960). Actually, the wrap up of Dressed to Kill (1980) beats it at its own game, but Brian DePalma’s indicative lack of subtlety makes even Hitchcock look like Andrei Tarkovsky.

In an echo of the pathologically obedient son who costumes himself to unleash his id, the filmmaker was possessed by a late-onset artistic adolescence. Alfred Hitchcock was, by 1960, a supremely experienced and formally confident director. But after the relative disappointments of Vertigo (1958) and North by Northwest (1959), both critically and commercially, Hitchcock seems to have suffered a minor crisis. Of course, now these films are esteemed as some of the director’s best work, but at the time Hitchcock’s sweeping, suspenseful set pieces were being outgunned by schlocky, low-budget horror films. And so in a way Psycho is a rare late-period bit of pandering, but a wickedly disdainful style of pandering. In conversation with Francois Truffaut, Hitchcock, referring to Psycho, gave one of the best descriptors of his directorial style, “I was directing the viewers. You might say I was playing them, like an organ.”

There are traps that the film leads us into through gossip and distraction and half formed expectations these create. Then, with disarmingly casual brutality, the film upends us and seems to take pleasure in punishing us. It’s as though Hitchcock were sneering in the editing room, and through teeth clenched on a cigar saying, “You want trash, I’ll give you trash like you never seen.” And it works with dynamic energy. Psycho is taut and confrontational but delightfully macabre. No one is more in on the joke, either, than the established director trying to prove he can still run with the kids.

The story and the characters toy with acceptance and expectation. The emergent protagonists are easily the most dull and nondescript on screen. And so who to relate to but poor, long-suffering Norman? And yet how can you? And still you do. Though it’s practically an aside, Janet Leigh may be the most brilliant and fully realized female character in all of Hitchcock’s films. Small surprise, then, the fate the director has in store for her. To say Hitchcock had trouble relating to women is criminally understated; controlling and vindictive seems to have been his baseline. And so often, as with psycho-analysis, the appeal here is repressed and accidental. The work indulges and exaggerates lust, shame and perversion, and all good plots tend deathward. So, don’t forget to call your mom.

Psycho

1960

dir. Alfred Hitchcock

109 min.

Screens at The Brattle Theatre Sun May 14th @ 1PM

Happy Mothers Day!