If you’re anything like me, you spent much of the month of November feverishly trying to burn through your watchlist on Filmstruck. For those who weren’t lucky to subscribe before it succumbed to a fatal case of corporate indifference, Filmstruck was a streaming service co-curated by the Criterion Collection and Turner Classic Movies, and as such was one of the only places one could stream countless hundreds of the greatest films ever made. To many, it was an invaluable (and affordable) source of cinematic education, while I saw it as a handy way to shore up my credentials by filling in some egregious blind spots (I used to have nightmares about being ousted from my post when it was revealed that I hadn’t seen a single film by Terrence Malick). By the time the service went dark on the 29th, I had forcefed myself perhaps more than the daily recommended dosage of cinematic art, but I also managed to walk away with a few new favorites.

One of the more pleasant surprises I found as I worked my way through the infinite queue was Black Narcissus, the 1947 epic by British fabulists Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. Powell and Pressburger are popular namedrops in cinephile circles, thanks in no small part to effusive praise from the likes of Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola (as well as the pleasing, lawyerly cadence of their combined names), but their work was just far enough outside of my wheelhouse that I’d never given them their proper due. As it turns out, I’d been an idiot: Black Narcissus is a frankly astounding film, and all the more so due to the time that it was made.

Black Narcissus tells the story of a convent of nuns, including the altruistic Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr) and the ever-so-slightly unstable Sister Ruth (Kathleen Byron), who are sent to found a mission in a remote Himalayan town in northeastern India. At first, the sisters take to their new environment, teaching the children and tending to the village’s sick*. Soon, however, things deteriorate, as cabin fever sets in, tensions with the locals rise, and the nuns find themselves at each other’s throats– both figuratively and literally.

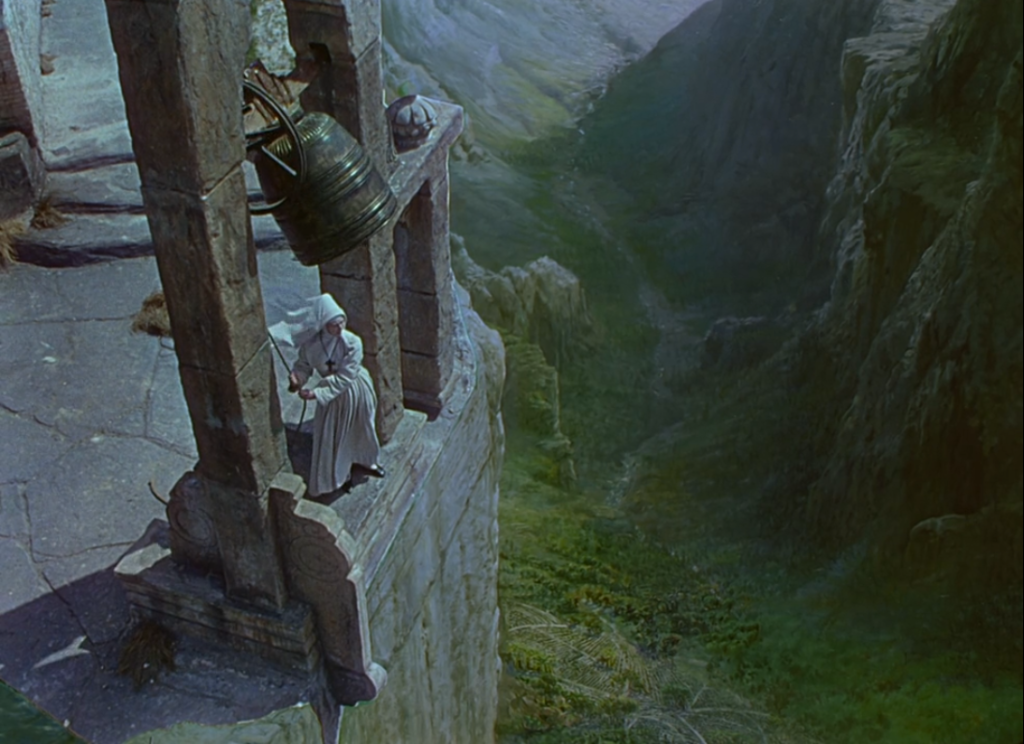

The first thing a contemporary viewer will notice about Black Narcissus is that it is fucking gorgeous. Rather than taking the conventional route of epic filmmakers and traversing to the Himalayas for some choice location footage, Powell and Pressburger chose to shoot almost entirely in a UK soundstage, faking their exteriors by use of truly eye-popping matte paintings. This allowed for some otherwise impossible shots (check out the dizzying, repeated image up top of Sister Clodagh ringing the bells over a gaping chasm), and, more importantly, gave Powell and Pressburger a level of color control that would have been impossible on an outdoor set. There’s a reason why Black Narcissus was selected for the MFA’s fascinating Color Tells a Story series, where it represents the color red; Powell and Pressburger use color the way some filmmakers use music, expertly deploying just the right hue to convey each emotion.

Then there’s the subject matter. While the repressed sexuality of nuns would provide fertile ground for exploitation filmmakers a few decades later, it’s disarming territory for a big, glossy 1940s studio epic. To be sure, this isn’t The Devils, but the frankness with the film portrays its characters’ sexuality is a far cry from A Nun’s Story too. By the time she fully snaps, Sister Ruth looks and acts like she’s stalked in from a Hammer horror film, and even the seemingly pure Sister Clodagh is plagued by flashbacks to a forsaken love affair. Interestingly, Black Narcissus almost certainly could not have been made in the United States at the time; the Hays Code, which policed the content coming out of Hollywood, was heavily backed by the Catholic Church, and its infamous list of “Don’ts and Be-Carefuls” included “ridicule of the clergy” among the former. As it stands, it was many years before Black Narcissus would be shown uncut in the states, with Sister Clodagh’s inner life being the most significant casualty.

All of this speaks to just how singular a film Black Narcissus is. It neither looks nor acts like any film of its era– or, really, any other era. It’s the sort of film whose influence can be felt in countless others from the past 70 years, but which still manages to feel completely fresh when viewed from today’s vantage point. FilmStruck may be gone, and the streaming landscape is poorer for it, but if you’re reading this site, you likely live within spitting distance of multiple venues which offer just as many opportunities for cinematic discovery. Happy New Year– go see a movie.

*- I should probably point out here that Black Narcissus is about as racially sensitive as one might expect from a British film set in India made in the 1940s. While the nuns’ ultimate failures have been read as a critique of colonialism, the portrayal of the Indian characters (many of whom are clearly played by white actors) remains problematic. It’s not quite Birth of a Nation, but regardless, one should probably proceed with caution.

Black Narcissus

1947

dir. Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger

101 min.

Screens Sunday, 12/30, 3:00pm @ Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Part of the series: Color Tells a Story