During the pandemic I started a job at Whole Foods. It happens. Things were fine for a while, I guess.

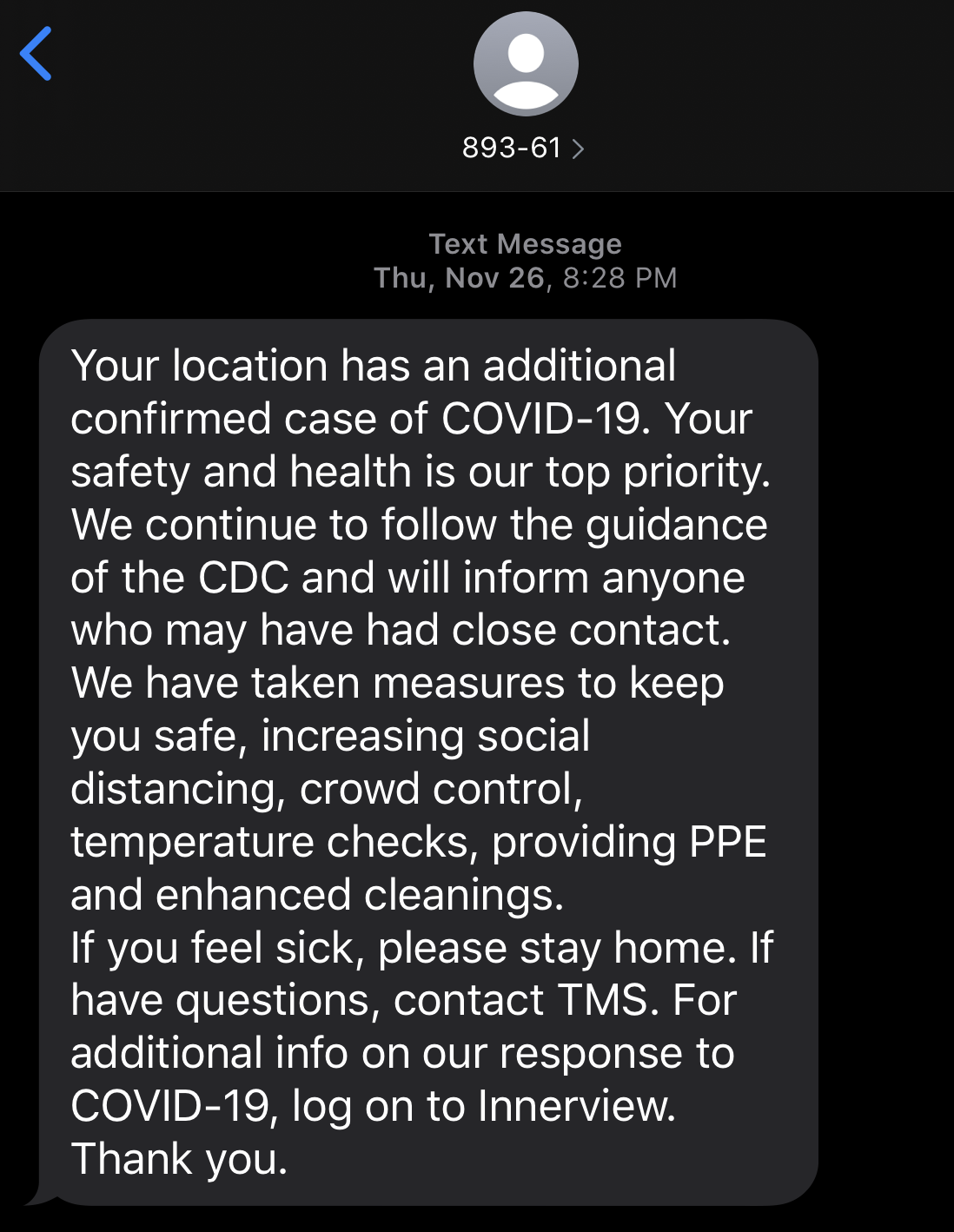

On Thanksgiving Day, I started receiving text alerts from Whole Foods’ corporate messaging service. The body of the text is as follows:

I received 4 of these texts in about a week. Some of the texts had alternate wording in a very crucial area: instead of an “additional case,” it read “additional cases.” For this reason, I can venture that there were, at the very least, six new cases in a week, starting on Thursday, Nov. 26th.

I was told that the majority of the new cases had come from the bakery section. On Black Friday, the section was closed with all team members instructed to get tested. The employees were back by the end of the weekend. A few days later, on my break, I received one of the pluralized “additional cases” alerts while on my break.

Questions that swam beneath my consciousness began to gasp for air. Are the overnight employees told to stay home while the store deals with COVID-19 cleaning? Does the store ever close, or are there always people in it? After a confirmed case, what gets sanitized besides the person’s section? The elevator, the break room, the locker rooms, the toilets, the kitchen?

Did it even matter what team you were on? We all used the same microwave.

The questions formed an urgency in my mind. As someone with four roommates (two of whom work in medical facilities) and two high-risk parents in their sixties, I I’d have nowhere to live if I got sick.

I quit the next day. On the phone, my assistant supervisor confirmed the lack of containment when he told me that last night’s cases “had come from Amazon shoppers, not the bakery.” He said he understood my concern, and wished me luck. That was on December 4th. Since then, I’ve received two more alert texts, bringing the sick count to a minimum of 10 at the point of this writing.

I can’t help but compare my ordeal to the experience of my friend, Barry*, who works at Trader Joe’s. The last time we saw each other he spent an hour expressing his frustrations, fears, and predictions for supermarket workers as COVID-19 slid into its second wave. One thing he said, about Trader Joe’s corporate, knocked in my head for days afterwards. It knocked when I told Whole Foods I quit. He’d said:

“They are not going to do anything about the situation until a lot more of us get sick.”

MITCH McCONNELL, AMAZON, AND HEALTH THEATER

On the heels of Mitch McConnell’s successful campaign to keep $900 billion in funds away from civilians, most Americans find themselves either sick, jobless, or some combination thereof. The reason for McConnell’s stance, according to Time Magazine, was to create a “liability shield…for companies and organizations facing potential COVID-19 lawsuits.”

Fittingly, The Senate Majority Leader’s verdict was only just preceded in the news by the double gut-punch of Amazon hitting one million employees, and the launching of an international campaign by a number of its employees.

After Black Friday of this year, The Intercept reported “[c]oordinated strikes, work stoppages, and protests of varying size… in Bangladesh, India, Australia, Germany, Poland, Spain, France, the U.K., the U.S. and beyond,” by an international movement called Make Amazon Pay–a difficult proposition at the very least, but I count myself among the hopeful.

With McConnell in charge, Amazon has yet to see its day in court regarding COVID-19 safety violations (at least in the U.S.), but, really–what do they expect us to do in the meantime? Don’t Amazon, its subsidiaries, and countless other companies, expect us to riot for our bread and roses sometime soon? How do they expect to pacify us?

“All we’ve done so far,” Barry said of his store’s safety protocol, “really just boils down to a form of ‘health theater.’”

While the term ‘health theater’, or versions of it, is gaining popularity in its own right, Barry likened it to running around with a fire extinguisher during a five-alarm blaze.

To him, the lack of corporate willingness to intervene and create official safety mandates has left a dearth of authority in his store if he notices a safety infraction during his shift, his task is to either put himself in direct danger, or just let it slide.

He contrasts the panic he feels every day with the cheerful script he is given by his store, one that he must then give to the customers: We’re doing everything we can to ensure your safety.

Barry was hardly placated by this. “Just because you can’t see my face underneath my mask,” he said, “doesn’t mean I’m smiling.” But there’s a reason for health theater’s proliferation: the illusion of efficacy goes exactly as far as one is willing to believe in it. It’s reassuring, and people want to be reassured.

There is a surface and an underside to health theater: the former is the store employees’ attempts to fend for themselves, to make up protocol and safety measures as they go along.

The underside is the machinations made by these companies–a cynical game of maintaining competitive edge while evading liability. These designs are laced with a bloodthirsty optimism that does believes that the worst can’t happen. Until, of course, it does.

THE SURFACE: FIRE EXTINGUISHERS IN A BONFIRE

Even in the best of cases, a business will prove itself fallible if it leaves its every defense to its on-the-ground employees. The vague promises of increasing social distancing, crowd control, and enhanced cleanings from the Whole Foods alert texts are all things a store manager has to enforce.

At Whole Foods, everyone on the ground is as susceptible to the virus as everyone else. That means that it really doesn’t matter who comes in sick: the woman who runs the store, her small army of Store Leaders, the Team Leaders and their Assistants, and all of us shelf-stockers, kitchen workers, cashiers, and maintenance people all have an equal chance of becoming infected.

There’s also only so far a store policy can go–things fall through the cracks. There is no designated “sanitizing officer” in Whole Foods or Trader Joe’s. In reality, these duties get diffused to the point where anybody could shirk them without repercussions. Barry noted that, when it came to proper use of PPE, fellow employees were more likely to let their masks slip below their noses and mouths than customers were.

Mostly, says Barry, the problems he faces at his Trader Joe’s store arise from the company being “reactive, and not proactive.” He recalled that customers would often remark about missing protocols, such as the lack of plexiglass by the registers, until eventually it was installed.

Proactivity, to Barry, would mean putting more extensive cautions in place and actually having the guts to enforce them before anything bad happens.

“They [Trader Joe’s] haven’t done anything forward thinking, and they haven’t done anything to try to make us more safe than what’s necessary,” he added.

Trader Joe’s also has a policy listed on its online COVID-19 update (most recently revised on 11/20/20) that states their policy of closing and cleaning stores once a positive case is discovered. Barry confirms this; in early October a crew member’s test came up positive and the store was deep-cleaned the next day. On-shift sanitation, he says, has not changed much:

“There’s hours of time where people aren’t sanitizing at the registers,” he says.

Whole Foods’ form of surface health theater, which does not include closing the store for cleaning, involves employee temp-checks, multiple hand-sanitizing stations, PPE on offer, and alternated walking paths. The sanitizing efforts seemed pretty bog-standard to me, at least in my section, but I didn’t see what they looked like before.

If a worker has additional concerns, they are welcome to go log onto their employee app and read Whole Foods’ corporate statement to its wage staff:

Like the alert texts, the language about what the company was doing remained terse and vague, but what it asked of its wage employees was explicit. The onus for the enforcement and success of these measures is clearly up to the employee. And it’s clearly not working.

THE UNDERSIDE: THE ECONOMICS OF SICK WORKERS

To a certain extent, all open businesses have to reconfigure their budgets to account for COVID-19 precautions. But each business with an on-the-ground staff is doing an equation to figure out how to maximize profits while still accounting for new concerns.

At some point, some of these businesses must have looked at the potential of a COVID-infected workforce and realized that allowing their personnel to get sick would be a cheaper option.

Whole Foods has taken positive measures in their own right, like giving sick workers additional time off and adding $1.5M to their Team Member Relief Fund. However, the costs of regular temp checks, PPE, donations, and whatever enhanced cleaning is can be accounted for.

Loss projections become a lot more intense when faced with a company-wide decision to close the store. It’s not a financial issue that can be resolved by moving figures around in a budget, but instead must be speculated upon and taken as a calculated risk.

Barry mentioned being greatly unnerved by the lack of enforcement at Trader Joe’s, which he attributed to the company’s reputation as a “nice store.” This doesn’t just extend to customers. Barry mentioned an immense amount of time and effort made by store management to make sure the actual workers were getting along and meshing with each other.

At Trader Joe’s, with an added concern about folks getting along, enforcement of COVID-19 regulations becomes a political issue that involves a lot of striking the right tone and not deviating from the brand. This could be why, as Barry would have it, the managers there are so reluctant to be proactive.

“We can’t be firm with people,” he said.

He also said mentioned that hiring managers took special care to find “somebody who gets along well with the crew and meshes pretty well … and has an attitude that is going to fit with all of the other employees.”

In his store, Barry has observed very few cases where an employee stands their ground against a safety infraction:

“Nobody feels comfortable doing it,” he said, if they’re going to be the only one.

THE NICE STORES

For a long time, both Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods have enjoyed a lot of acclaim for the services they provide for employees, which include 401Ks, health, vision, and dental insurance, accrued time off, decent wages, and discounts. (It should also be mentioned that neither of these stores allow workers’ unions.) In both stores, the language accompanying one’s working experience is that of care, concern, and vaguery.

These perks are undoubtedly a little better than PPE and temp checks, but, like PPE and temp checks, they fall under the category of fixed expenditures. Their costs do not have to be predicted, and no risks need be taken with shareholders.

In order to be proactive and not reactive, a company cannot simply hope for the best. It has to enter a speculative arena where the potential for lost profits must contend with the potential for lost lives. COVID-19 has confirmed that this is something few businesses are willing to do.

However, with McConnell’s verdict furthering the protection of utter infallibility of megamegacorps like Amazon, there seems to be little impetus for a company to suddenly turn a new leaf.

Thus health theater is a perfect interim strategy because it forces employees into complicity. When we run around with a fire extinguisher during a bonfire, we’re not only trying to contain a potential hazard–we’re trying to protect the reputations of our employers. Oftentimes, we’re forced to choose between the two.

In the long run, companies that refuse to take measures for their employees put everyone in danger–which means their beloved customers are next up in the line of fire.

Will corporations abandon health theater and take responsibility before it’s too late? Or, like Barry and his coworkers, will we all just have to wait until a lot more of us get sick?

The answer will come in 2021…

*Name changed to protect privacy

It shouldn’t be “getting sick” that scares you. You’re seeing restaurant after restaurant as well as every retailer with a soul go under while Amazon and mega-retailers and fast food chains thrive. Fuck politicians, fuck journalists, fuck big tech.