The Kalampag Tracking Agency is a 67-minute program presenting experimental films from The Philippines and its diaspora. In Tagalog, Kalampag is a bang or a clunking noise that draws attention to something that isn’t working, like a broken machine. The screening was screened as part of the Balagan film series.

One of the curators of the Kalampag Tracking Agency, Shireen Seno, was there for the screening. Outside the second floor of the Coolidge Corner Theatre, there were sheets with the program description. I read through the back:

This is by no means a representative program. This selection is personal, subjective. Like the works assembled here, the act of assembling this program is itself informed by a certain agency, by an independent urge to act on one’s will.

On the other side was the list of films. They were mostly short: the longest piece ran for nine a half minutes. Seno spoke about the screening and introduced an idea that stuck with me throughout the hour-long program. The films are low-resolution and came from a mishmash of older formats: 35mm transferred to video, 16mm presented on 35mm, 16mm transferred to 2K. Although there were films made as recently as 2014, the low-resolution aesthetic common among the pieces (even when it wasn’t intentional) subverts the high-resolution, going against the grain of the fetishization of the HD video that has now become mundane.

The films deal with a lot of different themes and moods that seem to have very deep histories that might require tracing (if you ever have the time to) to fully comprehend, especially if you weren’t immersed in the culture growing up. I was personally in the halfway spot. Although I am not Filipino and didn’t know many Filipinos growing up, I saw some styles, themes, and politics that reminded me of what I saw growing up in Indonesia that don’t exist in the American media.

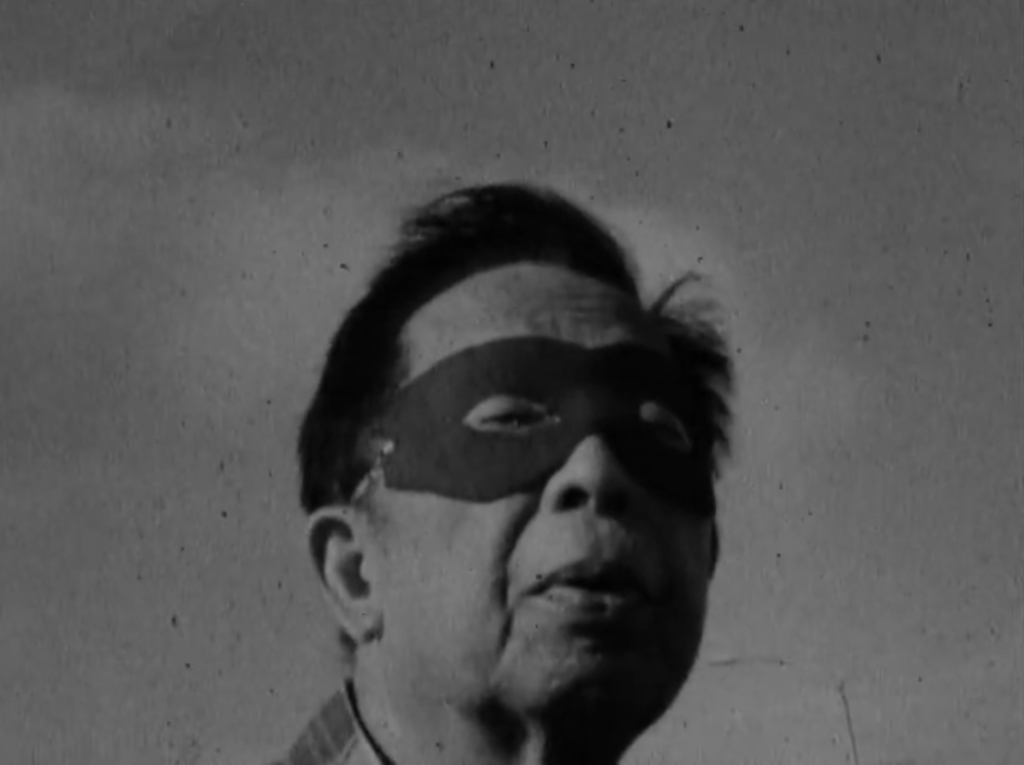

However, the privilege of viewing a curated screening is that it allows you to start piecing together these ideas as different threads flow between the movies. A significant portion of the screening deals with the Philippines’ relationship with America. In Kalawang (Rust) by Cesar Hernando, Eli Guieb III and Jimbo Albano (1989), images of a Filipino man and woman initiating sex is interspersed with images of the American military. There is a dissonance created when the footage of the couple, incredibly intimate even within a room in the house as they disappear behind a veil above their bed, cuts to an archival footage of a shirtless old white man spraying a young Filipino woman with water outdoors, surrounded by other men, implied to be from the military. In the background plays the Andrew Sisters’ version of Rum and Coca Cola, a calypso from 1945.

Since the Yankee come to Trinidad

They got the young girls all goin’ mad

Young girls say they treat ’em nice

Make Trinidad like paradise

DROGA! By Miko Revereza (2014) explores the flipside of the American-Filipino relationship. The film, shot on Super 8, presents Los Angeles as seen by Filipino immigrants. One segment contains a woman dancing to rock music as a voice speaks about how she was watching the television about the flood in The Philippines, talking about a man’s hallucinations. We see shots of American storefronts, an old arcade, video plazas, as a man lists things that they didn’t have (“…no uncle, no auntie, no electricity, no television…”) before repeating the phrase, “He no longer knows Tagalog.” It’s unclear whether this was scripted or unscripted, but this laundry list of did-not-haves represented things we don’t think about losing as immigrants. The low-resolution images from the Super 8 presented the feeling very well, as though we are thrown to the past lives of these people as they first arrive.

A film that to me felt very exploratory of its medium, and quite unique, is Very Specific Things at Night by John Torres (2009). In it, a 5-minute clip of fireworks going off on new year’s eve in a side street in a city grows quicker and more intense as the film progresses. The film was shot on an old phone camera – like the old videos you’d record with a Sony Ericsson, Motorola, or Nokia. Although you couldn’t make out the faces of people in the video, every bang of firework that goes off flashes very distinctly on the screen in a total change of state. Initially, you can separate each firework going off as you hear a loud bang. Eventually, the fireworks ignite in quick succession, and the bangs start sounding like distorted noise music that, along with the image quality, brought you back to a very specific slice of time where people actually used these phones.

Another thing to be said is how closely the style of some pieces felt when viewed together. A lot of the films had scratchy film-like qualities, almost jittery movements with lo-fi sounds that cut between scenes of grander things, like the ocean, the metropolis, or the military, with smaller settings, like a class picture, a murder in a room, or a procession. It turns out that the workshops held by the Goethe Institut in Manila had a big influence in some of the pieces, and it was quite interesting to see how the style and influence permeated throughout the span of the few decades that these films were made in.

But beyond the coherent history of filmmaking, the anti-imperialist resistance, and subversion of the high-quality, I felt that, most importantly, this curation presented a version of The Philippines’ past that exists in Seno’s memory.

British novelist Kazuo Ishiguro was born in Nagasaki, Japan and moved to England when he was five. In an interview with the Asian American Writer’s Workshop in 2015, Ishiguro told Ken Chen about memories in his writing:

When I first went into writing, I was actually interested in my own memories. The act of writing and remembering were intimately entwined. In fact, I would say that I probably started to write novels because I wanted to preserve my memories of Japan – at least what I thought were my memories.

There are three reasons why I think that Ishiguro’s approach to writing is at least subconsciously analogous to the curatorial process behind this screening. The first is the choice of low-resolution images inherent to some film formats, and the importance of proper preservation to keep film alive. The second is the curatorial statement mentioned above on how the selection “is personal, subjective.” The third is Seno’s background as a Filipino immigrant in Japan who studied in Toronto and my personal experience as someone who hasn’t lived in their country of birth for 11 years.

Memory is hazy business, and everyone is susceptible to misremembering things as each iteration of your recall builds upon the previous time you remember something. People try to immortalize their past through photographs, diary entries, and accumulating things, as memory alone will disappear or transform into a distant feeling. A film in the collection serves as a fitting equivalent. The only copy of Tad Ermitaño’s The Retrochronological Transfer of Information (1994) previously only existed in a subtitled VHS copy of the original 16mm film until it was transferred to HD video for the series. Analog film, when improperly preserved, will discolor, collect scratches, and eventually disappear “into vinegar,” as mentioned during the screening. In fact, recalling a hazy memory is like watching an unpreserved experimental film of your past: you understand the general plot, sometimes it’s hard to hear the sound, but overall, you understand the emotions you felt during that event.

Watching the series made me notice a couple of things from my past. ABCD by Roxlee (1985), animates an alphabet list with innocuous words from “L is for Laugh” to more loaded words, like “D for Dictator.” The animation style reminded me of illustrations that I read in Indonesian joke books from the 1990s. Some dated fashion from the 1980s shown in Bugtong: Ang Sigaw Ni Lalake (Riddle: Shout of Man) (1990) reminded me of the costume design from old Indonesian movies and photos from my parents’ youths. Seno must have seen something that reflected her memories of The Philippines of her past in these experimental films. Of course, unlike the similarities I saw in style and fashion, the films would have interacted with more complex memories and spirit of being Filipino.

Of course, there is a certain sense of academic and artistic importance in preserving experimental films from The Philippines, and I’m not saying that these films were chosen out of feeling alone rather than a deep historical understanding of the film world in The Philippines and beyond. But I think a part of why these films were chosen and preserved is that Seno wanted to share with us her memory of The Philippines.

I encourage you to see the next iteration of Kalampag when you have the chance.