Rashin Fahandej’s work offers a stunningly intimate portrait of fatherhood by articulating its absence. From a low hum set to a growing wave of pixels, the exhibition swells to a quiet symphony, swallowing the viewer in the unflinching gazes of men. The exhibition text explains that these fathers are“community members and formerly incarcerated [fathers].” As the exhibition’s title suggests, the interactive installation is set to the songs these fathers sing for their children. Vacillating across mediums, “A Father’s Lullaby” explores the visual, aural, and tactile dimensions of the father figure. In a striking attention to perspective and presence, Fahandej scales the viewer’s experience to that of a child, for whom a parental figure can loom large and enveloping, delineating the limits of the known world, at least for now.

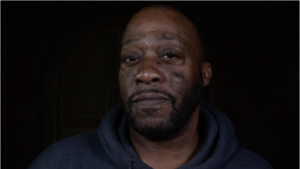

The exhibition deftly negotiates a large-scale approach to the issue of incarceration and the degradation of the familial unit with quiet, painfully specific insights into the experience of fathers without their children. Murmurs and mumblings of a kind I can remember from my own childhood—when my father would mold the lyrics of the classic bedtime lullabies around the familiars and knowns of my small world—fill the room. All men who took part in the research project were invited to sing to their children, though the exhibition does center on the largely marginalized voices of returning citizens. On the back wall, the men’s voices and bodies are burst apart, pixelated into a rising wave that matches the welling emotions in their voices. Along one side, they appear in panels, staring bluntly into the camera. These panels work to establish both comfort and discomfort for a viewer. They emphasize each particular father and his special message for his children. Yet this display also showcases the men as members of a more somber chorus.

Fahandej’s artistic choices allow her work to highlight the scope of this issue, but also remind the viewer how easily people with specific lives, stories, and families can be abstracted into thousands of dots, left to disappear into a system in which they are nothing but a number. Fahandej’s guiding belief that “the lives of ordinary people [are] extraordinary” allows her to present a larger systemic critique while retaining the integrity of the individual relationships in her work.

The duality of Fahandej’s display remains even in the smallest details of the exhibition. To engage with the interview component of the show, viewers must place their hand onto a glass panel, which illuminates with an opaque, golden-yellow light as one of the men begins to speak. In order to be able to hear the entirety of a given subject’s interview, the viewer must keep a hand pressed to the glass. The imagery of a row of people, given only an auditory means with which to interact with someone on the other side of the glass, is unmistakable. Yet there is more to this image.

In an interview with WBUR ARTery in March, Fahandej explained: “I feel like witnessing somebody else’s story deeply is a sacred place. You have to come to it, be giving, and be vulnerable yourself.” This kind of simultaneous vulnerability and disconnect is a familiar sensation to Fahandej—as a Bahá’í woman born in Iran, she was forced to flee from her home and has continued to experience this distance as her art becomes increasingly public and political in nature. To WBUR, Fahandej confessed: “To think you are uprooted in a way that you cannot go back […] It was a very, very difficult kind of realization.” The sustained contact required in her exhibition invites the viewer to engage, to “give,” as Fahandej puts it, contact, time, and attention in order to hear someone’s full story. Even more profound is being able to hear, in the pauses and breaths taken during the interview, the same father humming to his child on the wall behind you, a quiet reminder of the power of song to make presence transcend the physical. Even in the childhood experiences of some of these men, the presence of a father took on more than one meaning. As one man recalls in his interview: “I never knew my father. My mother was my father.”

Viewers interact with the interview components of A Father’s Lullaby. Image courtesy of Rashin Fahandej.

Fahandej’s exhibition has made the rounds throughout Boston, and in the coming week will be supplemented during its showing at the ICA with a panel “Intervening in Mass Incarceration: From Narrative to Action.” Among the speakers will be Fahandej’s close collaborator, probation officer Jeff Smith, who facilitates a Nurturing Fathers program designed to help reintegrate men into society as they near the end of their sentences. In this small room, out of the way of other open, airy spaces within the ICA, Fahandej has cultivated a sense of intimacy that propels quickly into urgency. This “Poetic Cyber Movement for Social Justice,” as the ICA and Fahandej describe it, offers a window into the experience of fatherhood. That is, Fahandej’s work also shows how the compound effects of systemic racism, incarceration, and poverty radiate outwards from the most specific and special of bedtime rituals between father and child. Don’t miss this exhibition, which affords its audience a profoundly destabilized experience of family and community. Fahandej will also be speaking this week at the ICA along with other experts in a special supplement to her show.

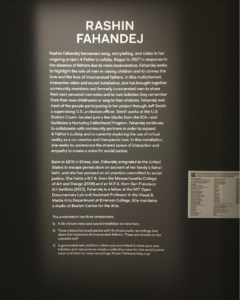

Text accompanying the show at the ICA as part of the 2019 James and Audrey Foster Prize exhibitions.

A Father’s Lullaby is currently on view as part of the James and Audrey Foster Prize exhibition at the ICA through the end of December. More information on the exhibition and the event can be found here.