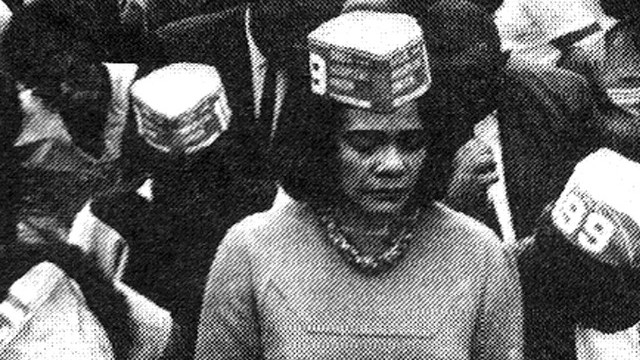

I Am Somebody (1970) is the most prolific piece of Madeline Anderson’s work. From synthesis to significance, the film tells the story of 400 black female workers who protested the conditions at the Medical College Hospital of the University of Southern Carolina, showcasing the narrative as viewed by Anderson – a black female herself. It captures an air of authenticity in its selection of subjects and makes decisively political statements in the imagery presented (i.e. a foreboding image of the militarized forces surrounding those one strike, some armed with assault rifles, others wearing full olive drab). Anderson’s work – this film and beyond – feel eerily reminiscent of the cultural climate today, the images dated only by their grainy quality and the struggle contrasted only by its decade.

It is as one audience member put it, “The kind of imagery we need out of modern-day documentarians.”

Listening to Anderson share her story and vision, I was struck by the ways in which she approaches not only this industry but life more generally as an outsider. There’s little doubt that African American women are quickly forgotten whether it’s the way our news is broadcast or by virtue of the “angry black woman” stereotype that pervades our culture. What we miss in these representations is, as Anderson describes it, “the true voice” of the black woman.

All of this being said, it becomes clear why Anderson faced some stigma early in her career. She was fighting an uphill battle in a white-dominated industry facing societal prejudice and navigating a pre-Civil Rights era. The social climate here was thankfully on the verge of national discussion and, knowing this, Anderson pursued a career independent of the white filmmakers she had helped in the past. Her road to joining a film-related union was hard – riddled with conflict and a threatened lawsuit on her part – but definitively earned by the time she had gathered enough resources and friends to create Integration Report One (1960), a reel which surveys the early days of the Civil Rights Movement.

The work attracted the attention of filmmakers like D. A. Pennebaker, individuals who realized the unique vision Anderson had to offer the larger documentary industry living as both an outside worker and an inside voice.

Sitting through her screening – the aforementioned I Am Somebody, Integration Report One, and another piece of her work, A Tribute to Malcolm X (1967) – the stories played out like snapshots of a history I’d read only in books. The voices which struck me were the ones of people living through these times, the people whose lives were impacted by the events transpiring around them. All of this was paired with a realization that, as I wrote before, these were the stories we needed to see more of and that Anderson’s voice is one we desperately need today.

This is not to condemn the documentaries that are being made today. There is a certain charm to the Morgan Spurlocks and Michael Moores of the world (aka the edgy, pudgy white dude) but what we really need are people experiencing the important issues backed by the industry so they can tell the story their way. While the intent is in the right place, I can’t help but feel that white filmmakers with grants and distribution are overshadowing those people of color who are unable to tell their story in an accurate and meaningful way.

In short, the personal touch that Anderson brings to her films is apparent as it is relayed through her demeanor as well: She has grit in every sense of the word, a tenacity to make claim over her own image and identity no matter the cost. As she ages into a world which reminds us of how little progress has been made, I can’t help wondering where her successor may be if they have not already been chosen.

And for that person: Good luck.

Integration Report 1 (1960), A Tribute to Malcolm X (1967), and I Am Somebody (1970) screened as part of the Harvard Film Archive’s Say it Loud! The Black Cinema Revolution series.