Standing alone in the middle of a gallery, surrounded by the bustling sounds of the Green Street T-station and encased in various sets of VR goggles and headphones, I felt quite the picture of my generation. As one of a set of freshly minted college graduates who have been, under the guise of ceremony, somewhat unceremoniously tossed into “the real world,” I have found myself clinging to the comfort of what I believe I can still control. Among these aspects of my life is my virtual presence. Swaddled in the comfort of a platform which brings everything within a scroll’s distance from me, I increasingly turn to my digital self to provide a constant in a sea of unknowns. It gives the impression of aggregating the parts of myself—friends, family, familiar haunts—that have scattered across the country and the world over the past month. Boston Cyberarts’ exhibit Body Mass opened my eyes to the complications of grounding the self on such shifting sands. The world wide web, in making even the most familiar content available to you, requires something in return, and scatters a version of you to its farthest reaches. This all happens with a single click, and due to its speed this phenomenon is rarely interrogated for what it is: an investment of the self in something that is much less stable than it seems. Something happens here—a change, a dilution. What happens to our understanding of the self as seemingly coherent, individual, and agentive when it is beamed into the oblivion of html? In the exhibition Body Mass, ten artists attempt to capture the status of selfhood in the age of social media. This review focuses on three pieces from the exhibit which question the integrity of the self as it appears filtered through the blue light of a screen. I chose to focus on these three pieces as they most expressly deal with the visceral and corporeal aspects of marginalized bodies, and the ways in which they are warped and twisted in the digital realm. To me, this is one of the exhibition’s most powerful angles.

In her work BLOODLESS Series, Lani Asuncion deftly explores the fraught relationship between a sense of place and a sense of self in her short film series made up of three installments: Lydia: Bled, Displaced, and Barren: Lei. The saturated colors, split-screen shots, and disjointed human forms that populate Asuncion’s screen all invoke a sense of fracture. This tone is particularly apt given Asuncion’s choice of subject—the series skewers the American annexation of Hawai’i in 1893. The “bloodless coup,” as it was called, is given a new valence by Asuncion in her own conception of bloodlessness. Lydia: Bled features an intimate diary entry of Queen Lili’uokalani’s from 1893, but the sense of female power, and even female presence, remains just out of reach. In her depiction of the female form, Asuncion amplifies Queen Lili’uokalani’s refrain “the bones of my bones the blood of my blood,” lamenting an intimate connection between self and soil that was irrevocably severed. Legs peek out behind a plant, a woman’s back retreats from the viewer, two hands weave a lei, but the entirety of the female body is never displayed. In one segment, a woman hits the bottom of a plant against her thighs, the falling dirt leaving the roots close to dangerous exposure. Each frame suggests a slow erosion of connection, both bodily and environmental. Asuncion’s message is clear: something primordial and incredibly important was interrupted, here.

Lydia: Bled from Lani Asuncion’s BLOODLESS Series, film. Image courtesy of Boston Cyberarts.

To me, the title BLOODLESS enhances the violence of such a rending of people from place, rather than diminishing it. Though almost uncomfortably bright, saturated tones of red are present throughout the series, there is a palpable absence of the warmth and vitality of blood as it connects people to place and to one another. Instead, the BLOODLESS series highlights the absence of such a connection—the people do not bleed, they are bled.

Artist and self-proclaimed “poet of code” Joy Buolamwini joins Asuncion in focusing on a sanitizing narrative of the self in her piece AI, Ain’t I A Woman? Inspired by Sojourner Truth’s historic speech, Buolamwini’s video piece feeds the images of famous black women into the Watson Visual Recognition software by IBM. Invariably, the images of famous, powerful women such as Shirley Chisholm, Oprah Winfrey, and Michelle Obama are recognized by the algorithm as men, apes or other animals, and at times are even rendered unidentifiable.

Joy Buolamwini, AI, Ain’t I A Woman?, film. Image courtesy of the artist’s YouTube.

In Asuncion’s piece, the viewer can readily identify the bias in the narrative of Hawai’i’s “‘bloodless’ coup” in the words written by American government officials. Buolamwini, however, seems to argue that we lose this critical eye when presented with a seemingly objective, inhuman algorithm. Here, history’s victors hold more than a brush and a can of whitewash—these methods of dehumanization are more insidious, couched in the supposedly objective and unbiased realm of binary code. Of Oprah, Buolamwini says: “Even for her face well known, some algorithms fault her, echoing sentiments that strong women are men.”

In an exhibit centered on the self, Buolamwini’s work reminds us of the sometimes unsavory aspects of humanity that are retained in the digital realm. Binary is not without bias. Having identified the prejudice inherent in the algorithm, Buolamwini pushes back against it by emphasizing her own familial connections and the recognition of the powerful black women who have shaped her life. Like Asuncion, Buolamwini plays with an absence and presence of blood, highlighting the life force that connects black women to their relatives and their “sisters” in a wider sense. The questions that form the heart of her spoken word piece are plaintive, powerful ones: “Can machines ever see my queens as I view them? Can machines ever see our grandmothers as we knew them?” Her poem fills the viewer’s ears while phrases such as “walrus moustache” and “coonskin cap” envelop legends Shirley Chisholm and Ida B. Wells, as Oprah is mistaken for Michelle Obama, while Obama’s own natural hair is identified as a “toupee.” In short, Buolamwini skewers the artificiality of artificial intelligence. It can only scan the surface of a person—the level at which prejudice and generalizations flourish. Yet, Buolamwini’s piece reminds us that the Watson software results are not merely a “data-driven mistake.” She reminds her viewers that there is something deeply and darkly human about AI, asking us to think about the dominant human consciousness after which AI is modeled, to confront its ingrained biases and prejudices. Ultimately, Buolamwini’s message is an empowering one: she returns a sense of community and empowerment to the identities of strong black women who cannot be reduced or conflated by an algorithm. In the face of such diminishment, Buolamwini says: “we laugh, celebrating the successes of our sisters.”

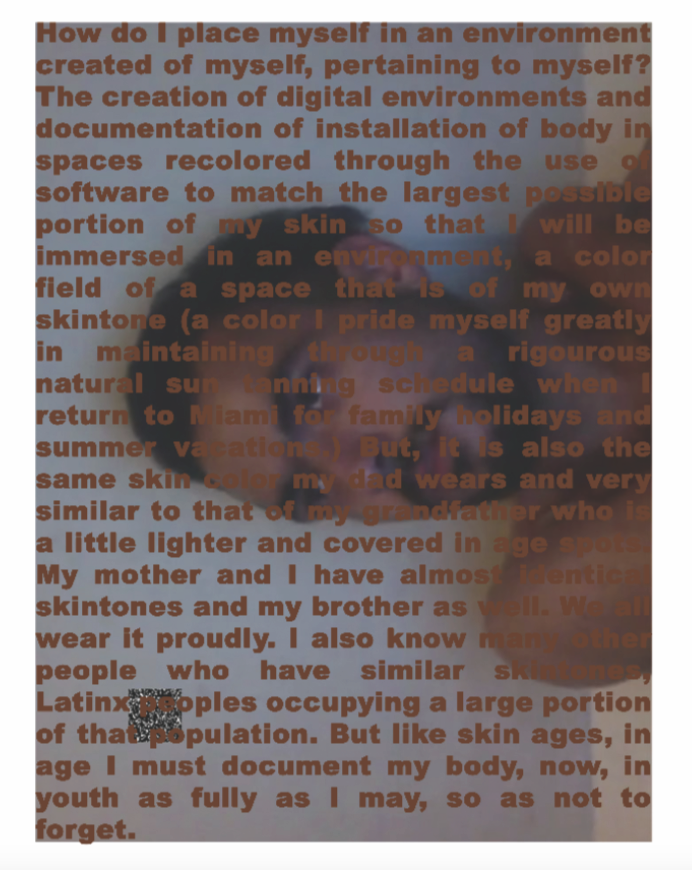

Danny Bryan Gonzalez explores another dimension of digital recognition. In his pieces My Skin Tone on the Web + #663300, Gonzalez uses a software to generate a swatch of his skin tone, using this to reconfigure the space around him until it is “recolored.” Gonzalez seems to be pushing back against the same force Buolamwini is critiquing. My Skin Type on the Web declares a radical ownership of the computer-generated self—Gonzalez rejects the simplifying and silencing force of computer code by becoming the agent that dictates its outcome. In the same way that he takes care to maintain an image of himself in the physical world through his “rigorous natural sun tanning schedule,” Gonzalez asserts control over the digital depiction of his skin and himself. The piece consists of two panels. #663300 is the actual color sample of Gonzalez’s skin tone. This color sample infused in every aspect of the second panel, My Skin Tone on the Web, which contains a picture of Gonzalez himself, and is overlaid with his description of the project. Using his skin tone as ink allows Gonzalez to inhabit an ambiguous realm between the self obscured and the self reclaimed. The digital swatch of his skin could potentially lean into the realm of reduction—it boils his identity down into a series of pixels. However, he reclaims the digitized self, this series of digits and data, and grounds it in his corporeal experience.

Danny Bryan Gonzalez, My Skin Tone on the Web. Image courtesy of Boston Cyberarts.

The sample of Gonzalez’s skin tone changes depending on the lighting and angle from which the viewer approaches it, suggesting that the nuance and depth of identity is not entirely lost in its digital form. This computer generated image, explains Gonzalez, “is also the same skin color my dad wears and very similar to that of my grandfather who is a little lighter and covered in age spots. My mother and I have almost identical skin tones and my brother as well. We all wear it proudly.”

To me, the question that drives Gonzalez’s work represents the aim of the exhibit as a whole: “how do I place myself in an environment created of myself, pertaining to myself?” This question encapsulates the tension between passivity and agency in exploring and curating the self in the digital age. How much control do we really have over our pixelated personality? What is translated, and what gets lost? While each work in the exhibit addresses this topic, Asuncion, Buolamwini, and Gonzalez imbue these questions with a racial, political, and historical context that makes their work especially poignant. Body Mass forces a viewer to interrogate the ways in which aspects of the self quite literally build a digital persona. We invest real, weighted pieces of ourselves on the web, and the line between our own cells and selves and the megabytes and binary code of the internet is not as clear as it seems. What’s more, as Asuncion, Buolamwini, and Gonzalez remind us, the intangible, digital self is capable of replicating and reinforcing societal narratives. Each of these artists calls attention to the dual power of the digital realm: it is capable of both uplifting and silencing marginalized voices in our society. Body Mass aims to make us aware of the true cost of these investments.

Body Mass, curated by Keaton Fox, is on view through June 23rd at Boston Cyberarts Gallery in JP. A closing reception will be held June 22nd from from 6 to 9. More information on the exhibition and the event can be found at https://bostoncyberarts.org/body-mass/