If there’s one thing I appreciate about The Sugarland Express (1974), other than its outlandishly talented direction, is the way it complements a film like Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967).

Where Penn’s film captures the on-the-road feeling of two gangsters traveling through a backward Americana, Spielberg’s work plays less on the importance of the criminal and more on the societal impact a Bonnie-and-Clyde-type character might have on an individual, a community, and a country.

For instance, one of my favorite moments in Bonnie and Clyde involves the “kidnapping” of Gene Wilder’s character, a moment which flips the switch between a character feeling comfortable with a crew of degenerates to an instant and pervasive unease. The feeling is short-lived, as Wilder’s performance is only part of a larger, more complicated picture, yet the scene stands on its own as a weird look into the relationship between citizen and criminal. The underlying question here is whether or not you can really trust someone on the run from the law.

Part of why I enjoyed The Sugarland Express is that it takes that moment and decides to absolutely live in there. Where Penn spends a moment exploring this question, perhaps unintentionally, Spielberg and crew lean into the relationship between criminals and folk, using a real world event as a backdrop for some incredible moments.

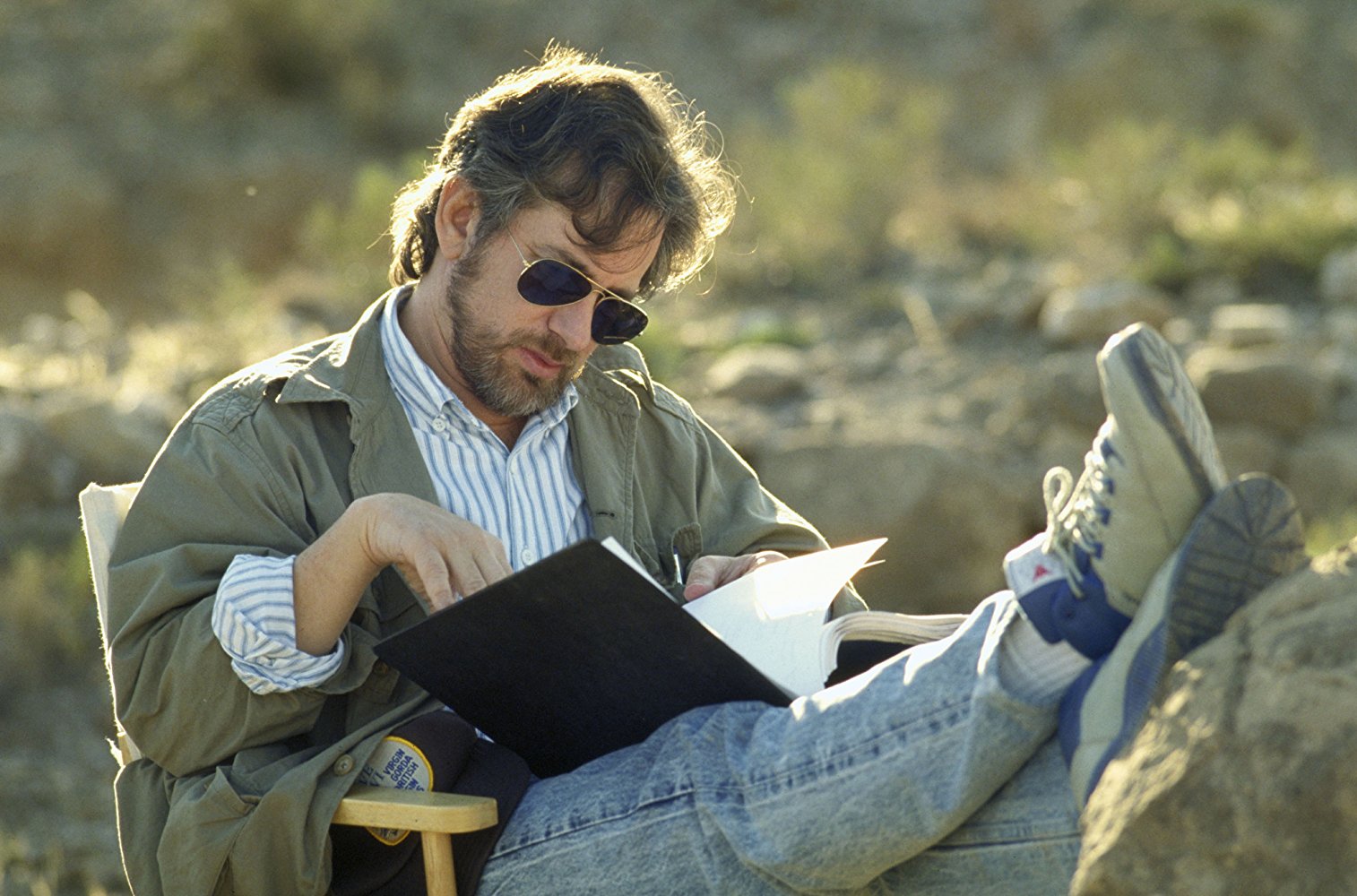

It should be noted that The Sugarland Express was Spielberg’s first theatrical directorial debut. A major hit with many critics (with the exception of Roger Ebert), it’s a film that bears the early hallmarks of the director’s later works. The most obvious of these characteristics is the way in which Americana is valued throughout the film, something Spielberg is apparently obsessed with in all of his work. It’s a story about real people doing real things and, at least from a visual standpoint, we really live with them.

Spielberg’s knack for placing viewers within a scene or familiarizing them with a certain Western or American charm is at full play here, almost lulling you into believing you’re watching something from a different era in film history, something akin to a John Ford or Howard Hawks venture. It feels distantly familiar, like you’re close to recognizing the full scale of the director’s potential, but, truthfully, the sheer force of that would come later and would realistically develop as a style over time. Yet, for as far as the Spielberg we know and love today might feel from the 1974 version, The Sugarland Express retains a distinctive touch over a familiar Ford/Hawks feel. And I’d say part of that comes from the film’s sense of humor.

Tell me you wouldn’t at least chuckle at this: Two criminals decide that they need to be together and reclaim their right to a family. After a failed attempt to commandeer a bystander’s vehicle, the two decide to kidnap and near-torture a highway trooper as they travel through Texas to reach their children. It’s essentially a story of two people who kind of have a just cause, but then let it fall to the floor with how they pursue it. It’s an irony that shapes much of what Spielberg is trying to achieve.

Drawing back to the Wilder moment from Bonnie and Clyde, there are always moments in films where good meets evil or, from a more lit-savvy perspective, where protagonists meet antagonists. There are always forces for change and there are always forces of complacency.

Sugarland frames a Wilder-esque moment as the crux of its narrative by focusing less on the rise or fall of two real-world characters and instead leaning into the journey they take with their kidnapped officer. This creates an ongoing tension between our main characters, and in turn makes the audience feel uneasy about the journey ahead. Trust me: This is intentional, and it’s the foundation for some great fun.

There’s a great rapport between Goldie Hawn, William Atherton, and Michael Sacks that allows for some genuinely funny moments. Whether it’s someone offering the kidnapped patrolman some fried chicken or a very real moment of concern for an RV they’ve just hijacked, the conflict between two criminals and a man of the law becomes a near afterthought to how the relationship unfolds. I can’t provide an answer, but I think there’s part of this film asking us whether we’d do the same if placed in a lawman’s shoes. Would we be willing to look the other way if the cause was just? How far would we go for two parents looking for a second chance?

It’s something that shapes the film’s humor, while also laying the groundwork for some fantastic empathy on the part of a single officer, as well as his responding unit and captain.

So regardless of Roger Ebert’s thoughts on Sugarland‘s treatment of its characters, I believe Spielberg had a very clear view of what he was trying to create from his ensemble. Sure, we might not see a lot of development from the characters we are presented with and, as you’ll notice upon a rewatch or first viewing, we’re also given a lot of different voices throughout the film. I believe the intent was not to create a few characters we as an audience might relate to, but rather to create a full span of characters and personalities that are representative of the time and place this story unfolds, as well as the distinctive American charm it offers. We know from Spielberg’s later work– and even his work on the his next venture, Jaws– that he is accomplished in the art of creating compelling characters. Sugarland was not a genuine effort at creating a small and compelling cast; it was something much more ambitious. It was an effort to capture true Americana, both in terms of its contradictory humor and its complicated questions.

I don’t want to spoil too much or make the film seem too heady and academic, so I’m ending this with a quick reminder that Spielberg continues to be one of the most prolific storytellers of this generation, and ignoring the earliest section of his catalogue would be foolish when you have such a fantastic opportunity to get out there and see it first-hand on authentic 35mm.

The Sugarland Express

1974

dir. Steven Spielberg

110 min.

Screens Friday, 1/26, at 5:15pm and 9:30pm @Brattle

Double feature w/ Who’s That Knocking at My Door

Part of the Limited Series: Who’s That Cutting My Film?

35mm!