I knew I liked Boston before I saw Frank Hurricane blow a line of coke off an amp the moment before he began his show downstairs at Deep Thoughts JP, but I liked it even better after this happened.

I came up in New Orleans hard on marijuana, and never fucked with coke until Erin gave me some on the cracked sidewalk snug against the whitewashed walls of Saint Roch Cemetery couple years ago, when I lived in that purple house between Music and Arts. Fucked with it maybe four maybe five times, the last time at the Horse Meat Disco last August at the Ace Hotel where I saw a man drink a liter and a half of his own pee, and was so fucked up that when they turned the lights on to indicate the party was over, I took it as a brilliant lighting move by the DJ: Oh wow! Brilliant! We’ve all been dancing in the dark and now we can see each other and feed off each other and dance til sunrise! I doubled down and kept fucking grooving. My best friend’s ex-girl dragged me out by the collar and we did more coke on Carondelet Street before I loped my long ass onto the first streetcar I saw and wide-eyed my way uptown, stepping slow and fucked through the lower garden district to my home behind the coffee shop on Race Street, stopping a moment to consider the fountain in Coliseum Square my beloved racist grandfather restored years back. His drug is the sazerac and if you ever go to New Orleans, which you shouldn’t because it has enough fucking shit to deal with right now without your ass muddling around in its glory, well if you do, definitely call me up, and I’ll take you over to his house, and we’ll get fucked up on sazeracs and his lovely accent, and maybe if things go alright I’ll take you down to the river and suck your dick, or if you ID as a lady maybe take it slower and more nervous because it’s been a while since I’ve been with a girl but fuck you look good and I like the way you talk and… hold my hand… Can I kiss you?

But this is a story about Boston and how hard it is to make the Great American Album.

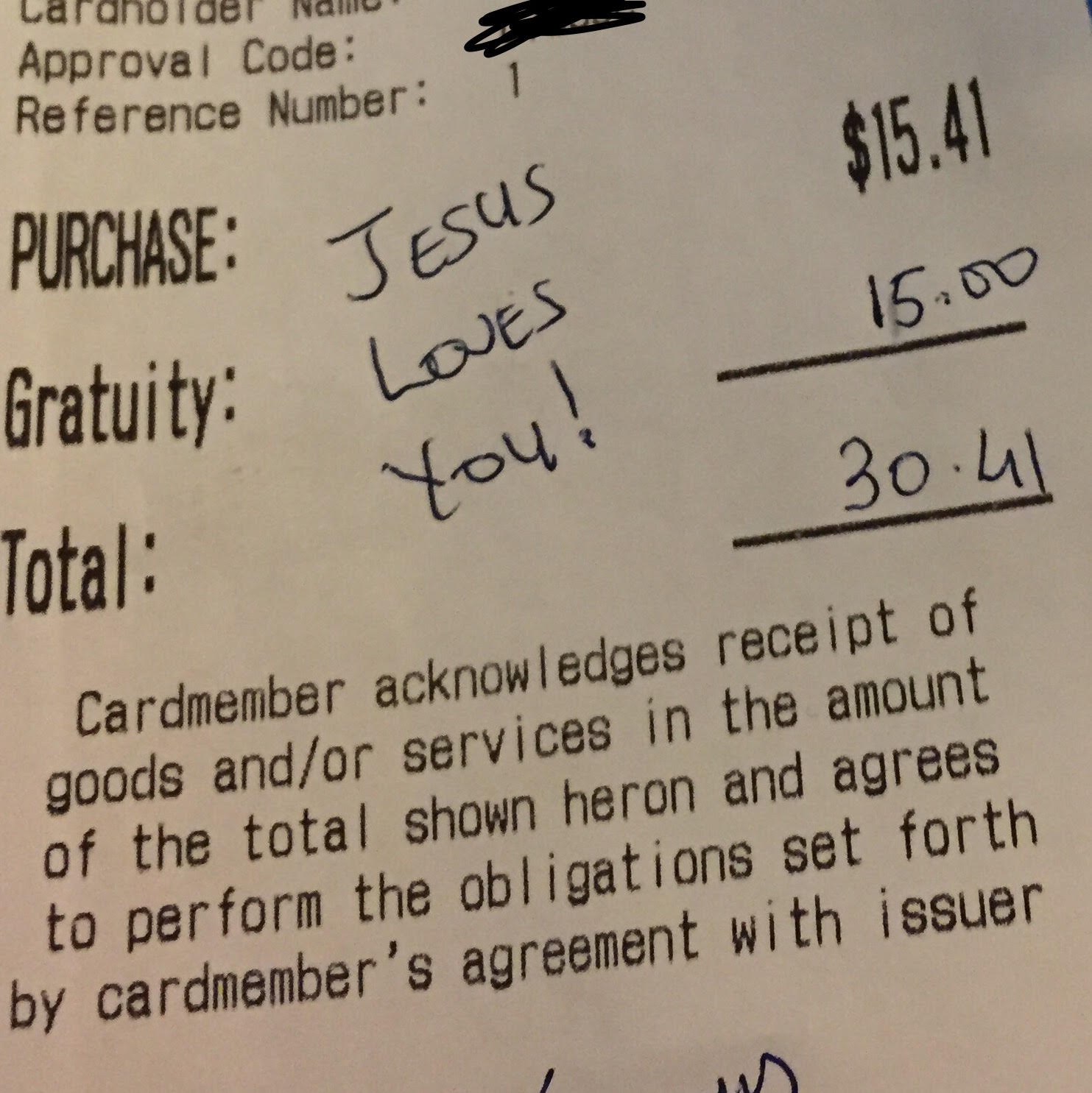

I got off my shift at the Café Pamplona in Harvard Square and stuck around to suck a fag down with Raoulph, a regular who tipped well, regularly paid the tab for regulars who were older and unhealthier than him, and while he didn’t tip over-the-top well (like the motherfucker who wanted to convert me and/or suck my dick who left me fifteen dollars each time for a regular coffee, “Jesus Loves You” always scratched on the receipt), he came behind the counter and poured his own damn tea and taught me how to use the POS machine because he’d been there so long, so I did exactly zero work for Raoulph, and bummed his Leavitt & Pierce rollies to no end, and he still tipped, so Raoulph is definitely a hero in this tale. Dark balding and charming, he always had some pretty thing wrapped around his ankles. Raoulph was some sort of magnet, which brought him plenty of good things but also maybe kept him pinned a little bit, stuck at the little table outside for twelve years, smoking, pissed, with a fat sense of humor and no sense of history. Like the fat priest who crossed the road to the church every day, or the endless stream of Harvard freaks who, year after decade, never age, like Sam the ukelele man and Grolier’s poetry shop, Raoulph was stuck in Harvard Square.

Not me. I had dreams to have and plays to write and glory to find, plus I was hungry and thrilled, with a Great American Album to record besides, so I bid goodbye to Raoulph , who didn’t hear, eyes being currently magnetized to whatever young science or philosophy freak with edible calves, and I wasn’t jealous but curious, but I marched off anyway toward Brattle Square, to catch the 66 bus, to keep moving, to keep seeing, to get fucked up, to get freaked out.

I decided I was marching too fast (fellow locals in New Orleans already mistrust me at my naturally northern pace). I can’t get too comfy up here, can’t get too sharp, too focused, less they reject me like a momma duck whose baby got touched by a white kid and smells too wrong and is left to die – so I stopped in to Charlie’s to have a beer and this lady down the bar had a seizure, and we all fell sort of respectfully silent, I’d never seen one before, still never felt an earthquake before, still never had sex with more than one person at a time before, still never been to London, or Detroit, or Kamchatka, or Oxford, Mississippi, so I was intrigued. Guy next to me says “Just watch.. Cambridge police and EMS’ll be here in sixty seconds” and before he said “seconds” we heard the sirens, no shit within ninety seconds there were two cops and about a dozen medical freaks, which shit made me just in awe of this town, one thing you should feel good about, dear sweet Boston and associated burbs, besides everything, is the basic functionality of city services. Keeps a Louisiana boy’s jaw on the damn floor. NOPD taking about eight hours twenty-two minutes if you call them and say your grandma is being held up by a dozen masked marauders. And that’s if you’re white.

Anyways the lady was fine, she came to pretty quick and went straight back to her beer, her girlfriend looked about ready to take her head off, “You never told me you have damn seizures” etc. etc. I got bored and downed the beer and crossed the street to wait for the bus. I’d bummed a rollie from Raoulph to go so I walked up to this guy and asked for a light, and he asked if I smoked weed, so we smoked weed together right there at the bus stop and talked slow and focused, he said This That Reggie Shit I Know You Ain’t Smokin This On The Regular and he made a big assumption there, but he was damn right, most white boys smoke that kind bud, and we talked about how he was headed over to JP to get an ounce from his lady for eighty dollars, which fact almost made me go with him, but we really hit it off, I told him how I was headed over to Brighton to get a measly quarter for the same price, I Bet That Gets You Right Fucked Up Though, and he was right, of course, it would, which reminded me I had a Great Fuckin American Album to get to out in Newton. The bus came.

The author hard at work on his first night in Newton observing American Whip Appeal fix the turntable.

The author hard at work on his first night in Newton observing American Whip Appeal fix the turntable.

I don’t have time to tell you about the journalist I met on the bus who was wearing a WWOZ t-shirt and I said, in the packed conveyance, You From New Orleans? Cos that’s a New Orleans radio station, turns out the motherfucker was headed there in the morning, “Oh I love New Orleans”, and I wrote him down where to go find the best po-boys and he told me where to find the best jazz, which he said was Wally’s on Mass Ave, which he was right about. Said he was proud of Boston, you wouldn’t recognize it from thirty years ago, was a racist shithole he said, and it’s gotten so much better, and I believe him, but America’s still a racist shithole, but I believe in us, maybe, maybe…

But I don’t have time to tell you about him because I’m on my way to the Album.

I hopped off the bus in Allston and popped up Higgins Street to snag cash and rolling papers from my basement apartment that I pay $0/month minus utilities for, long story. I got no bank in Boston so I got twenties and ones squirrelled away in socks and fuseboxes like I’m a fuckin laundering squirrel. I’m hyped. I’m ready. Great day of hard work and smooth schmoozin with the locals I’m ready to get the fuck out to the studio and jam. I stop at Blanchard’s for a pint of whiskey and wait for the B train, sipping openly in a desperate attempt to show everyone how much of a fuck I don’t give.

Train rumbles up the hill and I get off a stop too early. I knock on my pot dealer’s door, some gentle freak my boy James introduced me to. James doesn’t smoke pot unless it’s after one in the morning but he was kind enough to introduce me to his buddy from Newton South days, a great big lumbering stone. He opens the door with one hand and no eyes and I follow him to his lair. There is a stoned cat that is always very pissed to be so stoned, cat meaning cat here, and three cats sitting on a tiny loveseat, cats meaning humans here, one eye open between the all of them, sweet as could be. Bongs like nesting dolls arrayed on the desk, they’re taking hits of shatter or glass or whatever the fuck kids are calling it these days, you gotta use a blowtorch like you’re making fucking crême brulée or welding a skyscraper or some shit, and you stay fucked for a day, it’s way too much “Doin Drugs” for me, even though my boy Jordan back home is always doin it, always tryna get me to do it. Dab. That’s what they call it. Fuck no. There’s a vacuum cooker crackling in the corner making this shit, I look in the glass top and something dark is boiling, and I see the Globe headline, “Five Freaks Killed In Shatter Explosion”, so I back away and stay standing, idling nervously as he measures a quarter out. So. Damn. Stoned. And Slow. I set the money down on his XBox, shake hands all around because I’m southern and feel like I have to, and get the fuck out. Shit smells great. This album. Is gonna be. SO GOOD.

I take the train two more stops to the reservoir then walk over to Cleveland Circle and turn right for the long haul straight up Beacon into Newton. Why they ever took the rails out on Comm Ave past Boston College, why they ever took streetcars and rails out, replacin them with busses, all across this country… and ever since we’ve been in our selfish cars. Give me the sidewalk, give me the public bus. We’re all of us a selfish mess. I like being snug up against my fellow citizens. It keeps us honest. It keeps us open.

I cackle happily to myself, alone on the sidewalks of Beacon. I love Boston roads. I have a bird’s brain, a compass, a gut feeling for direction, and so Boston roads make sense to me, ancient highways, all… most cities burned and got rebuilt or were started as military outposts or just got laid out after 1800 in a grid, Age of Reason shit, but Boston is glorious with its roads… Newton Street gets you the fuck back to Newton after you’ve been smoking at the Arboretum, Harvard Ave gets you the fuck to Harvard, Comm Ave gets you the fuck out to the hinterland… this shit makes sense to me. First night James found me pot I got so damn stoned and walked eight miles listening to Frank Ocean and writing elegies, glorious timeless poems, paeans to Boston streets, the most sensible paths in the nation. Boston I love you. I was feeling so good it was clear this album was going to record itself and ship itself over to the Grammy offices and win everything, we were gonna be famous, it was going to be right.

Dann, James, and Pat – Americans.

Dann, James, and Pat – Americans.

I climbed right past the dumb, sexy lemmings of Boston College, making a mental note to Sleep With Them Later If They’d Let Me, quickly passing at the top of a hill the estate of the freak who started Christian Science, streamed through Newton Centre, and hung a left on Laurel, putting the red home on Hancock behind me, James’ home, house of ancestors, house of ghosts, house of labor, house of heart. Harry Pothead generation will get this: I left a piece of my soul in that house, tucked it in between the boxspring and the baseboard, in an attic room, and as long as no one finds it and smokes it, burns it, kills it, some little bit of me’s gonna live. But that’s a parallel story. Same universe. Different story. I got an album to record and I can’t afford to cry right now.

I hugged Crystal Lake, which used to be called something uglier James said, until they started cutting and selling ice out of it so they named it something which you’d think Aw Heck That Must Be Clean Ice. My first night in Boston, in June, before all of this happened, before everything, almost, James passed the coke to me and said Two Bumps, gotta get a good start. And I felt peer pressured and I only went halfway and we all went out to the docks on Crystal Lake and were supposed to All Bond, me and James and Hannah and Loon.

We got naked and they leapt in but I was high and cold and Knew that not jumping in was inauspicious, a bad augur for the summer, but I was cold and defiant, and James climbed out naked and tried to wrestle me into the water, but I’m gayer and more athletic than he is, so it was me who threw him in, and if I’d known that’s the closest I’d get to him the rest of this, My Great American Year, I might’ve thrown it all in and crawled back south and had the Great American Slumber. But that’s about me. And him. And expectations, and trust, and communication, and ignorance. As it is we went to Montana like we planned, and thank Jesus too, but that’s a different story, one about love, and that’s for my Great American Book.

Like I said now’s not the time for crying, now’s the time for fucking! And smoking! And getting drunk! And recording!

American Whip Appeal are a Boston-based country-billy band. Allergic to both Flip Flop Rock and Kids Music (“Indie”), the members are versed in both Hassle shit (quick, loud, dirty, the kind you pay $2 for pleading poverty even though you’ve a fifth of Evan Williams in your coat and coke you’ll do in the parking lot at the bottom of Rugg Road) and the best of good ole white American shit, whose nexus resides somewhere between the compass points of Dylan, Cohen, and Prine. It’s messy, the lyrics are sharp, beer is not to be kept on top the amp no matter how much you are feeling it, and there is plenty of room for laughter. Also James is in charge. A band of few rules and open borders, really. The Great American Band.

Now’s maybe the time to tell you I’m not in this band, whose goal was to record the Great American Album. Not really. I’ve got soul for eons and a sense for rhythm like a total freak, and I can whistle better than anyone in the country, and I can play Saint James Infirmary on piano as many times in a row as I want, in addition to Heart & Soul, and I’m a genius, but the only reason I joined marching band was to march in Mardi Gras parades and I never actually knew how to play the trumpet so I just memorized where all the C and D notes were and played them VERY loudly, and otherwise just mimed it, and besides they made a mistake when they were drafting up the halftime show so they slotted me in with the tubas, which was all the big boys, and they couldn’t rightly change the halftime show or else the Blue Jay wouldn’t look like a Blue Jay anymore so I was stuck miming trumpet, this tiny eighth-grade thirteen year-old ninety-seven pound little boy, in among these hundred eighty pound sweaty juniors, while the trumpet section got all the glory on the other side of the field, and come to think of it I think that older boy who was nice to me and stayed with me the whole time when we went to Disney World probably had the hots for me, which was chill because he was seventeen and I was thirteen and that was hot, what I’m trying to say is musicianship, for me, has always been a side-project to Gettin Fucked or Bein Cool or Getting To Be In Mardi Gras Parades which is any New Orleans kid’s obvious Want, so my major goals in recording the Great American Album with American Whip Appeal were less along the lines of “lay down historic trumpet solo here” or “Backup vocals like a fuckin Supreme there” than “Do Coke With The Band And Have Fun” or “Hopefully We All Have Sex Together And Laugh”.

But none of this was in my head, only joy, as I left the lake and crossed Centre Street toward Hannah’s.

Hannah is the kind of girl who is in love with two people at once: a dead man and her uncle. Smart as an American whip, Hannah’s appeal is obvious as an approaching weather system. To know she is coming is to lay down in a field and avail yourself to what is rolling in: a new pressure, a new view, refreshment of the brain, a certain laugh that, unheard til now in all your miles of wanting, sets your stomach to electricity, your nose to itching, and causes your eyes to lock in, and you can’t remember what you were planning to do before you saw her, or if you even had plans at all. Hannah may not always be right but she is always right on, and even if she wasn’t, the way she picks tobacco out of her teeth is very, very cool. A woman who trembles at Cohen and surges at Dylan, always ready for the next thing, the next score, the next smoke, always reaching for the aux cord, always learning, never, to me, unbrave.

Hannah’s parents’d gone west for the week. Two. We had a big ole house to ourselves in Newton Highlands, the kinda liberal-ass looking house I’ve never seen down south, all soft white maple floors and massive ranges, kettles and kitchen tools in primary colors, flush with Corita Kent prints and Eames chairs, working fireplaces, brushed aluminum banisters, four different ways to make coffee in the morning, and a bunny in the mudroom, which is a room that only fucking exists in the north. James’d spent hours dragging every piece of equipment from his basement in the red house to Hannah’s living room: his pop’s old Rhodes organ, his little cousin’s trumpet, seventeen guitars, a four-track thing he’d actually read the damn manual on (“Oh wow now I actually know how this thing works”), and a thirty of cheap, fine beer. I’d been slowly ramping up on whiskey and confidence, and with a joe tucked behind my ear, I approached number 32.

I could tell something was off soon as I looked in the window. There wasn’t enough movement. I came quickly through the front door and into the living room. Pablo came barking. James was sitting at a low table in the corner, headphones on, connected to the four-track, looking down. Hannah jumped up, much too excited to see me, clearly glad for the distraction. Dann and Pat sat calmly, nervously, on the couch.

Dann, whose full name was not Danniel but Daniel and acquired the second “N” on his moniker somewhere between high school and getting high, is another hero of this story. One day James and I took Mass Ave to its concluding point (fyi it dead-ends between some woods and a community college/prison) and took a right, finding ourselves on the old War Trail, and we got out on Lexington Common, and for a boy from Louisiana, who only ever read about P. Revere and Shots Took Round The World and Midnight and Bravery and Redcoats and White Men Saving The World in books, which is to say, it was all a fantasy, hard to believe Lexington and Concord were real places, much less suburbs of modern fat Boston, well I was thrilled, and it was cold and rainy but I flew around that green: James look at this! James they lined up here! James the British retreated this way! Look you can almost see it! James a boy died right here! James America started here! And he smiled and was happy for me. We kept driving until we got tired and filled gas and turned back to the city. James says Fuck It let’s go to western Mass we’re already halfway which wasn’t very true but we turned around and boys-on-the-road-on-the-run we drove direct to the VFW in Amherst and drank a pitcher of beer and pissed and laughed over the pool table. He showed me houses he used to fuck girls in and laugh, the tea house he took a date to when he found out she wasn’t twenty-one, the clock tower at Amherst College his dead dad stole an arm of the clock from back when he was alive and really living, I paid all my attention, and we found a dark house on a wooded road when the sun went away, it was cold, but Hannah’s brother Satchel opened the door and was so happy-what-the-fuck-you-guys-doin-here he made us whiskey-teas and a fire and all these roommates looked like ladies and witches and had hats and pipes of pot they kept sneakin out to smoke and one of them well they picked up a banjo and played a new song they’d wrote, real pretty, and I was blanketed by cozy memories of Vermont, where I’d lay with ladies, and kissed boys by town waterfalls, and took baths with my friends. The hills of western Mass leading on up into the land of gay Vermont must be America’s hopeliest, safest, magickest spot. The woods are safe, the politics are chill, and there’s weed around. Anyways this person mesmerized me for a second, with their voice so countrysweet, and I thanked them, and James told me That’s Dann’s lover, and I said to myself, Dann’s a lucky Dann, this lover a lucky lover.

Back in Newton, on the couch, what Dann’s eyes were saying to the rest of us was something his brain just didn’t know yet: in two weeks time, his lover would drop acid and fall in love at a Phish show and fly immediately away to Oregon.

Stories rarely go the way we think they should, the way we write them. Dann and his lover were never going to stay wrapped up in each other’s banjos and dangles brookside, and Prince Estabrook was a black man who got shot on Lexington Green because he wanted to be free. Massachusetts may have been the first state without slaves but it was also the first colony with them. Dann’s old lover, the white men who wrote my history book, and Stephen K. Bannon can suck my fat, ready, peace-seeking white cock. This country is for the brokenhearted and the clear-eyed. The Great American Album will be a black one, but us whites can still cry. Try.

Which brings us to Pat Walsh, the other Trying White on that couch, and the third hero of our story. Pat Walsh. Leon, Loon, Rat, son of a hundred names.

Pat was meant to meet James & me in Montana, but he had to go to New York and get his shit rocked first. He had to get back to Boston for a new I.D. and so he headed west in his Taurus five days later than he’d planned. James and I were waiting patiently drinking beer at the Wise River Club in the Big Hole Valley, but we’d been there a month and the tab we were leaving my dad was headed north of four hundred dollars and I was getting horny and angry and James was getting crazy and ready. Horny, too, I guess: I caught him one night slowly humping the warm, tumbling dryer. This turned me on and I tried to kiss him but the dryer, apparently, was giving him all he needed. Pat seemed to be hauling ass across America at forty miles per hour. “Hey man I’m in Detroit, this bar is wild man.” Four days later: “Man Chicago is crazy man, I’m gonna head up to Minneapolis.” Three days later: “I’m in Minneapolis” Six days later: “I don’t know where I am man this country is so big man I can’t talk man I’m at the diner.”

Finally he was heading toward Yellowstone, a half day from us, but we just couldn’t wait, and we told him to meet us at the hot springs, and each night we’d step barefoot down to the little gravel lot, half a mile from the wild seam of hot water that fell constant from the rock, and wait for him. He never showed.

We were in California when we found out. A deer ran into him. His car. He made it very clear he did not run into a deer with his car; a deer, it seemed, had made the choice to run into his car. Choosing to read this as a bad day, Leon-formerly-Loon-née-Pat checked himself into a forty-dollar Oregon motel for some much deserved rest, but the proprietor didn’t have his room key ready. She let him in herself and told him to come back in an hour for his key. He did so. As he waited at the counter, a man rushed in and asked for an ambulance. His friend, it seems, had taken too many drugs, and was dead. He died in the room next to Pat. He argued politely for his money back, eventually received it, and slept in the Taurus, head against the door that wouldn’t close right, because a deer ran into it.

Certainly, in more ways than two, America rocked Pat’s shit last summer, and you could see it in his face as he sat on that couch that night. What Pat didn’t know yet, and I did, was that he was an American hero. He was a mother hen sitting on a fabulous story, a story only he could tell, was witness to an America none of us had ever seen quite like it, and he had good reason to feel pain, but all he had to do was add some exclamation marks and take some deep breaths and realize that, perhaps, he was doing just fine: Got my shit rocked in New York! Wild bar in Detroit! Chicago is crazy! I have no idea where I am! A deer ran into me! Dude died in the room next to me! If you don’t like the way things look, look different.

Pat and Dann had whipped around the country already, years ago, eating tuna in the back of the van while James drove, the only one in the band with a license. They’d formed a band, they’d practiced, they’d skipped practice, they’d played shows, they were kids, they booked a tour, they’d driven to Oregon and back. They’d already tried this Great American shit, and already failed. And I think that’s what James was feeling, over there in the corner with his face down: set me free of these fools, give me new America, by god, give me fresh plums, new knees to suck on, new knobs to turn. One thing Great America doesn’t like is to be defined, and what was clear, that bright gold night in Newton Massachusetts, was the band had been here before. It had gone out and explored, tried some new dishes, licked some new faces, but it was back where it last found itself, and it wasn’t going to sprout. Not like this. Not with these fools, not with this blood.

If America is a bunch of highways, only one of them leads to the promised land. The others, millions of them, peter out. Some go on for hundreds of miles, paved even, before they get subsumed by the forest. Others are timid footpaths, impossible to follow after two hundred yards. Some are dusty, trusty, even halfway useful. Others are laid with clamshells. Still more are scenic only, ending in a loop, technically useless, until you get out on them at four in the morning, alone with your boy, on acid, with god. That night, at Hannah’s in front of the fire, with dogshit on the carpet, we got to the end of a certain byway. The end was lovely, drunk, and safe. There was a small yard to lay in, and an old elm even, to keep us company. But the scent was lost, the way was had. There was no going further. This had been a Great American Try, and if we’re smart we might realize the Try lies much closer to the Real Thing than we realize, that maybe if we’d bushwhacked just a little further we’d have found it, or maybe if we’d tried to go across the river rather than over it we’d have realized some crucial truth, seen some arrow pointing the way we’d otherwise missed. The land is littered with old pots and dead men. The end of the road is an anxious site. We knew we were surrounded by love, but we couldn’t all figure out how to say Yes at the same time. This particular Great American Album was dead.

Back in New Orleans I’m trying everything: dates with girls, brushing twice a day, yogurt, loofah, smoking more, smoking less, and last week I drowned the Great American Carrot in coconut oil and threw it up my Tiny American Asshole. You know, just kinda tossing things at the wall and seeing what’ll stick. Yes on dates, no on smoking, yes on carrots. Two steps forward and one step up the asscrack. I have 311 matches on Tinder and the closest dudes on Grindr are named GeauxDeepNow, GardenDistrictBJ, uncut4uncut, (anonymous), Jared, white twinks=A+, Matt, Leftist, Daddyzurk, JP, [banana emoji], and Brandon. I went on a walk with a sweet kid from the south part of Chicago, and he’s all smart and kinda clumsy, and wants me to help him find and plant a papaya tree “because we don’t have that stuff up there”. He’s down here Teaching for America or some shit and so I gave him my girl’s number so he can get weed now. I don’t know if I’ll see him again.

I get very confused navigating the gap between sexlessness and fucking, camaraderie and intimacy, friendship and partnership. It’s like I’m standing right over the magnetic pole, and my compass is going wonko in all directions, so I’m not at all sure which way to go, and Lord do I feel like I have to keep going, but really I’m right where I want to be and I don’t love myself enough yet to just be here and be happy. But that’s Great America, isn’t it. We have to keep going. Our center is forever on the move, and we have to keep dancing with our ears wide, if we’ve any hope of making it to death having lived. We don’t love every thing, but we want everything anyway.

The Dream may remain obscured but we Keep Looking anyway

The Dream may remain obscured but we Keep Looking anyway

I want a beer. I can’t stop drinking. I stayed busy for a week when I got home from Boston then realized Heck It’s Christmas one day at one p.m., went for a beer, and have stayed rather drunk since, about a week and a half. And I’m not making piles of cash, and they say the coke in New Orleans ain’t too fresh, so I’m not doing coke like I was in Boston, but that’s a lie because I did it last night, what do you know, Erin’s birthday. I walked home from my cousin’s whiskey bar “to go to sleep”, but rolled a spliff and opened a tall boy and unbuttoned my shirt. I felt my chest and breathed. I put on Bringing It All Back Home because it’s one of James’ favorites and I’m working my way through his catalog because I had wool in my ears and never listened to Dylan until I listened to James. I slide open the heavy window. My apartment used to be a brothel (New Orleans, Boston, the world, is full of little histories like this, and I am mad for them) and they called the workers’ rooms “cribs”. My room is one of these cribs. Small, two walls brick and two of plaster, two plants, a radio, a bookshelf, a chair I pulled out of an old Degas painting, and my bed, which is big enough for two.

I’m standin there, in my doorway, swaying. Swaying is the best I can do, I’m very drunk, and I can’t really bring my gaze up off the ground, but I am so happy, doing a slow little twist and groove, singing with Dylan so loudly, my shirt is off now, I’m thrilled. I weigh nothing. There is no time.

“Hey.”

Was that god. I look up. Yes. God wears dreadlocks and smokes a cigarette. God sits cross-legged on the balcony opposite mine. How long has god been watching me.

“Hey god.”

God lets his cigarette fall to the courtyard below, wet and fulsome with fern and brick. He steps silently down his balcony and crosses to mine. I am ready to be here. I back into my room and wait for god to come. He is in the doorway now. We look long. God smirks and floats in. He is hungry. I feed him oysters. In silence do I watch him eat. Dylan has wandered off somewhere. He will be fine, he knows the way back.

“Close the door” says god, and I listen, and we pray, now on our knees, now on our feet, the night long.

—

Back in Boston, before all this, I am scrubbing my balls clean for the third time in an hour. They hang low because they are heated to one hundred eighty degrees. I rinse and turn around to grab my towel: it has been taken. The people in the shower with me are taller and broader and I do not want to ask who took my towel. I walk naked into the common area and ask Eugene for a clean one. I dress quietly and pay Gene twenty-four dollars with a tip. As he fetches change I look up and learn about the Great Chelsea Fire of 1908. It’s funny, the things you had no idea about, and the things you never will. I cross the parking lot of Dillon’s Russian Steam Bath est. 1885 (don’t tell anyone, it’s a gem) and walk up Chestnut to Everett. I board the 111 and cross the Tobin Bridge alone with the driver. At the top of the bridge I walk up to him and we chat. The Tobin is New England’s biggest bridge, he tells me. The Other Green Monster. I turn to spit but remember I am inside. I stare instead through the glass doors at the fracturing lights of the city.

I change at Haymarket and board the Orange line. They called it the Orange line because it kind of parallels Washington Street, which makes a lot of sense. The Back Bay used to be an Actual Part of the bay. There’s a dam buried under Beacon Street, a dam that never really worked, so they cut down hills in the west, in Needham, and trained in the rubble, dumped it between Washington Street and the dam, and it took them eighty years but finally the Back Bay became all land by 1900. The only way you could get into Boston, by land, in the early days, was by the Boston Neck, on a road called Orange Street, a high road, a road leading south. In 1825 they changed the name of Orange Street to Washington Street.

I like the Orange train immediately. It’s big, subway-grade, a world away from the charming shitboxes of the Green line I’ve fallen hard for. If the Green line boards at Brookline Village and is standing patiently on her iPhone in a packed nine a.m. car to get to Park Street and on to a medical sales job in East Cambridge, the Orange line not only has no idea what time it is, but no memory of which station he boarded at, nor does it matter, for he gives no fuck. And in fact, I am seated in the same car as this man, who sips his whiskey openly, not in a desperate attempt to show how much of a fuck he doesn’t give, but because the man truly doesn’t give a fuck. Best of all is the T employee seated pleasantly three seats away, on his way home, who clearly sees the man drinking, and clearly doesn’t give a fuck either. We stop at Ruggles and two twelve year olds come screaming on. The next stop they scream off as five more scream on, and this train-wide juvenile horned-up game of tag goes on until they all run off the train screaming at Green Street.

I get off at the last stop and pick my way through pissing men and a road construction project that seems like some bureaucrat’s sick idea of a permanent public art installation, stepping quickly into Jamaica Plain. It is my last weekend in Boston. I look at houses and what they are made of. I think of being okay, and the parts of town I haven’t seen yet. I think of James. I think of my nephew. I think of James and Hannah, and if they’re already high. Right on cue they’re ahead of me, getting out of his car, and I force them right back in, and for a while, we smoke cigarettes together. We do cocaine and I buy us forties at the spa, and I think about how this is the last time for a while, and think immediately after how that’s a choice in thinking, that also any cigarette could be the last, and there’s other things to mark time besides absence.

I knew I loved Boston before I saw Frank Hurricane blow a line of coke off an amp the moment before he began his show downstairs at Deep Thoughts JP, but I loved it even better after this happened. My friends were nearby, but we stood separately. We can share spaces at the same time but we can never see the same thing, not exactly, and it freaked me out to be in love with two people who understood that so well. That’s what keeps the Great American Album so hidden. Dickinson, Whitman, Hurston, Dylan, Lil Wayne, Franks Ocean & Hurricane: solo actors. It’s easier to get one voice through. What The Band did, and Outkast, and Black Star, for a handful of songs, at least, was get together and get out of the way. I know it can happen again. I’ve heard the laughter in the basement, and as long as two people believe that it’s possible, we’re all in good shape.

haha what

Wow. Glad to finally know what happened for you in boston. This is your best yet, Pierre (French for stone) or delaronde (cajun for stoned). You are my true love and I truly know that you know it already.