Pictured: Collage of MCI-Shirley image w/ flag provided by Black and Pink Massachusetts

On Oct. 28, 2019, MCI-Shirley, a medium-security prison in Shirley, Mass, received a call from the family of Fernando Ribeiro, an LGBTQ+ individual incarcerated there. Fernando, known to friends as Freddy, had been falsely maligned as a “diddler” (a derogatory term for a child molester) by one of the guards and had since experienced a sharp decline in mental health.

As Black and Pink Massachusetts’ Executive Director Michael Cox explained: “Within prison hierarchy, the only people lower than LGBTQ+ people are those convicted of a sex offense. Those convicted are often brutalized by both their peers and guards, whereby this guard is intentionally instigating violence based on this false accusation.”

Leading up to the month of October, Freddy was put on mental health watch for a week, and then sent to solitary confinement for further observation.

While solitary confinement was purportedly for Freddy’s protection, his mental health deteriorated further—on Oct. 25, he sent his family a letter outlining his intentions to take his own life.

“Of course by the time you get a letter, a lot of time has passed,” noted Mass state Rep. Lindsay Sabadosa, an advocate for prison reform.

On Oct. 28, Freddy’s family called the prison and asked them to perform a wellness check. After experiencing pushback from the officer who initially received the call, Freddy’s sister was put on hold by the lieutenant, who went to check on him.

It was too late. The next day, MCI-Shirley confirmed that Freddy had committed suicide while in solitary.

Freddy was not alone in the abuse he experienced. LGBTQ prisoners at MCI-Shirley face many dangers, from dangerous cellmates to medical abuse, and in their struggle to improve conditions are up against a deeply rooted culture of abuse.

Targeted harassment

Prisons across the country are dangerous for LBGTQ+ people. But MCI-Shirley, where the nine individuals who openly identify as LGBTQ+ make up less than 1% of the prison’s entire population, is known to be particularly inhospitable.

In 2018, Randal “Randy” Carpeno and Richard were transferred to MCI-Shirley from the Souza-Baranowski Correctional Center (SBCC), a maximum-security facility in Lancaster, Mass. Richard put it bluntly: “Our odds are not good.”

Through living in the same unit and working together during their time at SBCC, Richard and Randy became close friends. After Richard arrived at MCI-Shirley, the two were assigned as cellmates and for seven months Richard and Randy lived together without incident. This was particularly important for Randy. As a long-term AIDS survivor, Randy’s physical health was an added risk he had to contend with, and one that often affected how potential cellmates treated him.

The period of calm wouldn’t last, however. In April 2019, as Randy took his usual place in the med line alongside 20 or 30 individuals, a guard zeroed in on him. As a lawsuit filed by Randy against the prison in November 2019 details, that guard in particular seemed to enjoy taunting him. According to the suit, she had actively sought him out on multiple occasions, even abandoning her assigned post to target him.

On this occasion, the CO in question told Randy to remove his hat. As Randy did so, another person asked: “What’s this, a new rule?” The CO turned to Randy, who had removed his hat without protest, and asked: “What’d you say, you faggot skinner?”

Randy, like Freddy, knew that he would be further targeted for being incorrectly labeled a “skinner” (a slang term for someone accused of a sex offense). He says he tried to de-escalate the situation, saying only: “I’m not a skinner. I’m here for murder.”

But the CO reportedly mocked Randy, holding up her hands and playing scared: “Is that a threat?” she asked. “No, it’s what I’m here for,” he responded. “I’m not a skinner.”

Randy was handcuffed, placed in segregation, and issued a disciplinary report for using threatening language against the CO. He was held in segregation for two weeks.

After Randy was sent to solitary, his cellmate Richard lived in constant fear of discrimination and abuse by new cellmates.

“Yesterday, I was locked in my cell [while] drawing when I heard a laundry cart come into the unit,” Richard told me in an email. Laundry carts are often repurposed to transport property during housing reassignments. “I was so unnerved that it might be yet another homophobic cellmate that I snapped the tip off my pencil without even realizing it.”

Dangerous cellmates

Richard explains that housing assignments at MCI-Shirley are a pressing issue for LGBTQ+ prisoners: “Where our problems first start, is with homophobic or [sexually violent] cellmates.”

In the months after they were separated, both Richard and Randy were continually targeted. Richard experienced harassment and had his cell robbed. Randy was forced to relocate multiple times after people refused to live with “a fag with AIDS.” On two separate occasions, he was housed with IV-drug users, both of whom had active Hepatitis-C—a serious danger for someone living with HIV.

For Randy, this level of neglect reached its peak when he was housed in the same unit as “Jim,” someone who had previously sexually victimized him while the two were at SBCC. Randy informed the guards of his prior experiences with Jim and asked to be moved.

Randy’s request was justified. According to the 2003 Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA), any “additional, relevant information” that would prompt a reconsideration of someone’s risk of being sexually violent should promptly be incorporated into the prison’s decisions about that individual. Despite Randy’s report, COs refused to transfer him. Jim attempted to sexually assault Randy in a matter of days.

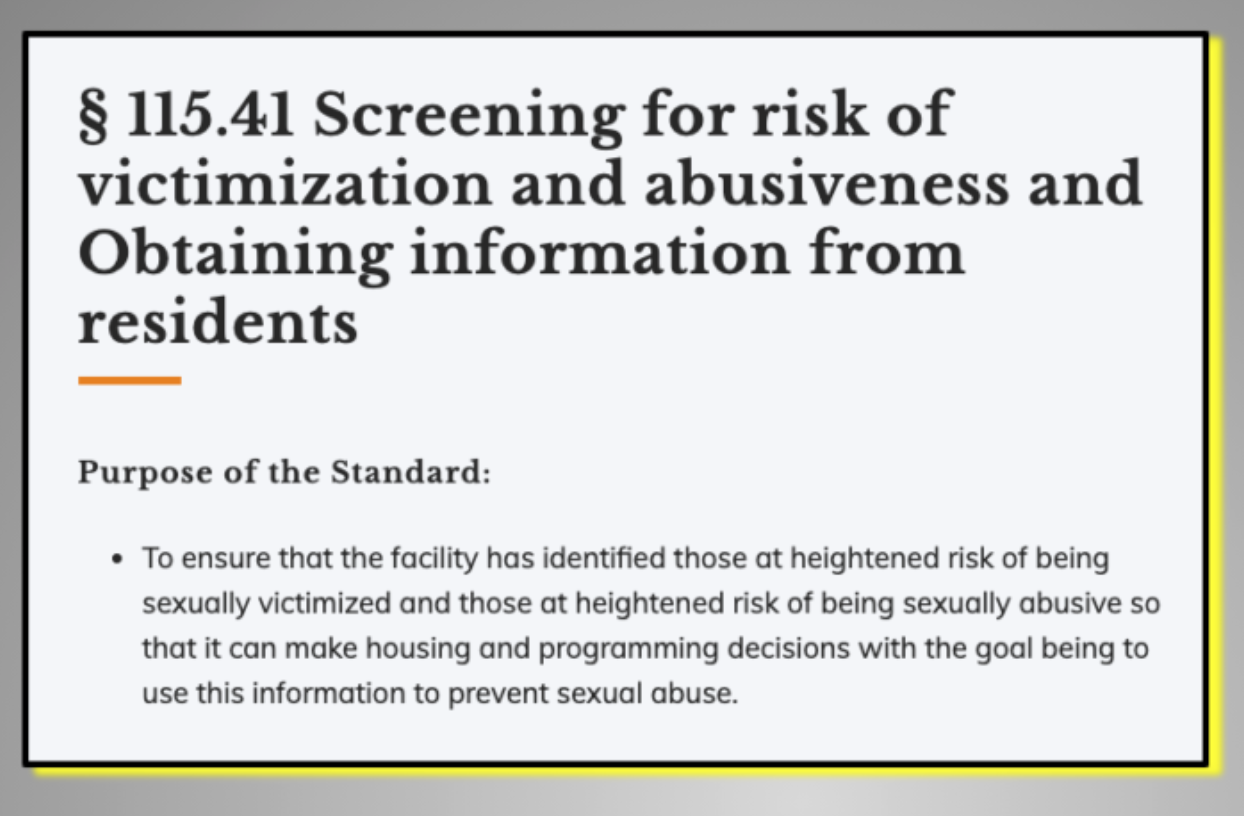

MCI-Shirley’s negligence appears to have been a direct factor in the abuse suffered by Randy. Under PREA Standard 115.41, prison staff are mandated to screen people during intake in order to identify those who may be at a higher risk of being sexually victimized, as well as identifying those who are more likely to commit acts of abuse.

Moreover, Standard 115.42 of the PREA mandates that the prison “use information from the risk screening required … to inform housing [and other] assignments with the goal of keeping separate those inmates at high risk of being sexually victimized from those at high risk of being sexually abusive.”

After Randy’s complaint, Jim was later investigated under PREA and subsequently transferred to another prison. However, the intent of PREA is to avoid these situations before they escalate to the level Randy experienced.

Village of misery

PREA standards have been made widely available to prison staff for many years. Still, this kind of attention to the basic safety and humane treatment of one of the prison’s most vulnerable populations is severely lacking.

In 2015, Charles N. Diorio, who was incarcerated there at the time, published an essay, “MCI-Shirley: A Village of Misery.” In it, he explains, “[Shirley] fails entirely to screen or assign inmates beyond placing bodies in beds. Little consideration is given beyond race segregation, gang affiliation, [and] other arbitrary and capricious cell assignment protocol.”

If LGBTQ+ individuals attempt to report violent and abusive behavior from cellmates, they are often the ones forced to relocate or be held in solitary. When Richard reported abuse, he was asked to sign waivers that cast the incidents as random, isolated events, rather than the result of MCI-Shirley’s refusal to follow PREA standards.

“If we refuse, we’re placed in segregation … until we agree to sign,” he explained. “It’s for our ‘protection’,” he wrote.

“Solitary confinement is a barbaric practice and we don’t need it. There are safe alternatives,” explained Bonnie Tennerriello, an attorney with Prisoners’ Legal Services of Massachusetts (PLS). But Randy and Richard’s requests to live together—a solution both men considered the easiest and most immediate redress for the threats to their safety—continued to be denied by administrators. Their housing preferences were dismissed as indulgent, though multiple cellmates had been allowed to reject them as cellmates based solely on homophobic sentiments.

The prison also employed the use of solitary confinement with F. (they/them), a 28-year-old nonbinary and gay individual who experienced discrimination and abuse from cellmates at MCI-Shirley.

On the afternoon of Aug. 14, 2020, F. was assigned a new cellmate.

“I told him who I was and how I conducted myself,” they told me. “I told him I wasn’t going to push up on him, flirt with him, hit on him, or look at him.” Two days passed without incident, but F.’s cellmate soon expressed discomfort.

“He said that I had to check off the unit,” F. explained. “I told him I wasn’t going anywhere and that he was more than welcome to leave the cell he moved into—mine.”

The altercation ended with a gang affiliate blocking the entrance to F.’s cell so that they could not enter or get their belongings. Fearing violence, F. relented, opting to be placed in solitary in the Restricted Housing Unit (RHU). They soon began the process of reclassification, hoping to be transferred to another facility.

In the time that F. awaited the decision about their transfer, they were held in the same unit as the individual who had initially threatened them. “He was telling people today that there was a ‘little fag boy here who had set him up,’” they wrote to me. “I am terrified.”

F.’s request for transfer to another facility was eventually approved. The new prison lacks the appropriate programs for them to continue their college education, but F. feels the trade-off was worth it. They wrote that as soon as they received the expedited results of their transfer, they began to cry.

“I felt overwhelmed with a sense of relief.”

“The runaround”

The actions of the individual who threatened F. were later classified as hate crimes, but Richard was skeptical that the district attorney would prosecute. He recounted an incident that occurred in January 2020 (corroborated by a timeline of events compiled by GLBTQ Legal Advocates and Defenders) where an LGBTQ+ inmate at MCI-Shirley named Edward was severely beaten by his cellmate as guards stood and watched. “Counting Edward,” Richard says, “this makes three hate crimes in about six months.”

Like Richard, Prisoners’ Legal Services staff attorney Bonnie Tenneriello is skeptical of Mass DOC’s internal mechanisms for accountability. “It’s very hard to get accountability,” she explained. “The only eyes in the room are the COs. So, it’s the incarcerated person versus the officer. The system is simply that the COs are in charge and there’s very little check on what they can say or do to you.”

This lack of accountability permeates almost every facet of life.

“In four years at SBCC,” said Randy, “I never had a problem with medication, PREA, housing, or anything else.”

Yet, after his arrival at MCI-Shirley, Randy was forced to file requests for even the most basic level of care. Among other medications, Randy was prescribed the HIV medication Truvada, as well as gabapentin (Neurontin) for severe neuropathy arising from complications with AIDS. Randy said that his Neurontin dosage was cut in half soon after his transfer to Shirley, and that he began to receive his Truvada crushed up at the med line window.

“Truvada specifically states on the package in large, bold lettering, ‘DO NOT CRUSH’,” he explained in a medical grievance in July 2019. “I asked the nurse and was told it was DOC policy to crush all medications. Since my medication is time release, crushing it may negate the effectiveness of the medication.”

Truvada is also most effective when taken at the same time every day. Yet despite continued requests, Randy was unable to get his dose on a consistent schedule. He filed a grievance on March 31, 2020: “I have told everyone about this problem and nothing is being done,” he wrote. “This must stop before it kills me.”

Eventually, Randy won partial approval on his grievance about the crushed Truvada. But because the prison ruling specified that Randy’s dose “will not be crushed at the [med line] window,” some nurses began crushing his medication at any other opportunity. He recounted one particularly vindictive instance of this behavior: “I was in the hole [solitary] and the nurse crushed my HIV meds. I told her I won the grievance and she said, ‘You’re not at the med line window now’.” When he protested, the nurse reportedly laughed and said, “You should’ve thought of that before you sucked a dick.”

Randy described scenarios like these as being given “the runaround.” His medical grievances travel through a kind of mobius-strip system—he is ferried between internal avenues that lead, invariably, right back to where he started.

Plus the pandemic

With COVID-19 raging through Mass prisons, and 1 in 5 prisoners in the US contracting the coronavirus, requests for medical care have become all the more urgent. Recently, Randy began to feel a pain in his chest. Worried that he may have pneumonia, he filed a “sick slip” asking to be seen by a nurse.

It took almost a month for him to be seen by a nurse practitioner, only to be told that she couldn’t do anything for him. She referred him to the infectious disease team, and Randy said after another two weeks, “Finally, I see the ID nurse, and she tells me that my HIV viral load is detectable. I was in shock.” According to Randy, his HIV viral load had been undetectable for 10 years prior to arriving at MCI-Shirley, thanks to medication and careful maintenance of his health.

Though he had explained his symptoms and requested to be tested for COVID during this same visit, it took another two weeks, three sick slips, and the arrival of the national guard at MCI-Shirley for Randy to get a test along with the entire prison population. “Surprise,” Randy wrote to me, “I had COVID.”

Because the cells in solitary were full of others who had contracted the virus, Randy was housed in a different unit that was typically used for punitive housing. This has posed even further risks to his health, he says, as it is difficult to request his HIV medication from within this restricted section of the prison.

“Solitary confinement has become the norm as a way to deal with COVID,” state Rep. Sabadosa explained. “Yes, if someone is COVID positive, they need to be isolated. But do they need to be locked in a cell? Deprived of medical treatment? The stories that I’m hearing from people who are COVID-positive are that the prison is [just] giving them Motrin.”

Legislators have been pushing for the DOC to issue at-home confinement guidelines as a step towards decarceration for those who are particularly vulnerable to the virus, or are nearing the end of their sentences. Unsurprisingly, they have been met with resistance. While the DOC agreed to write the guidelines after a court mandated that they do so, they claimed that it would take them until the spring of 2021 to prepare the directives.

“I think their hope is that, because prisoners are listed as one of the priority groups for the vaccine, they’ll be able to make the argument that they don’t have to release anyone because they’re not really sick,” Sabadosa said.

Limits of external help

MCI-Shirley has seen four changes in leadership in less than two years, with two terms served by Steven P. Kenneway. The prison is now led by superintendent Michael Rodrigues. But the facility’s culture of rampant homophobia and targeted discrimination against LGBTQ+ individuals remains prevalent.

“The homophobic culture is as strong as ever, if not stronger,” Richard reports. “There is no way to fix the culture here, [despite] the fact that they had four tries proves it.”

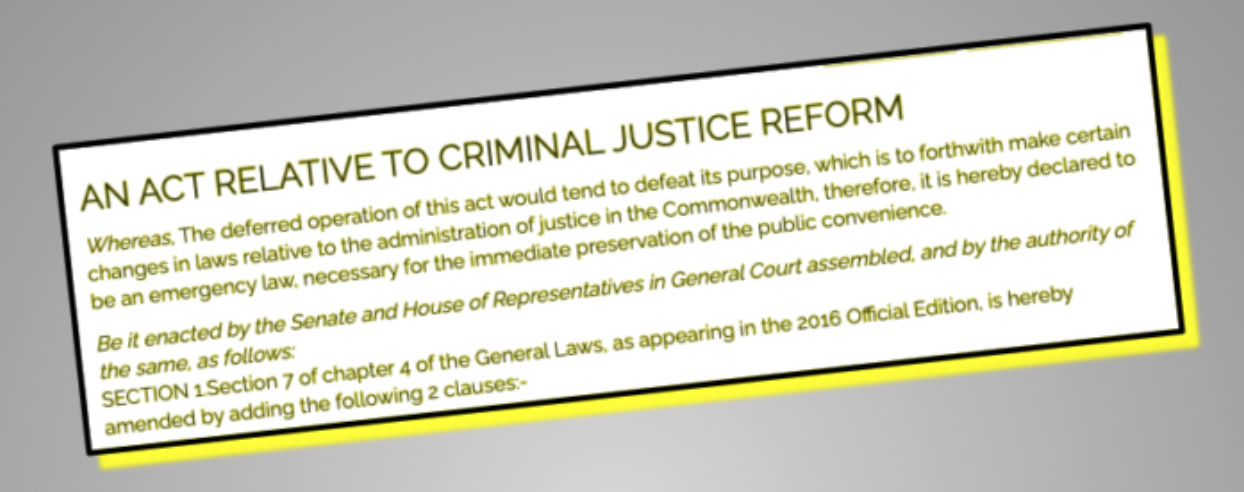

In 2018, Mass Gov. Charlie Baker signed the Criminal Justice Reform Act, a landmark bill aimed at tackling recidivism and addressing the dearth of resources for particularly vulnerable populations in the state’s prison system. While the CJRA saw the establishment of the Special Commission to Study Health and Safety of LGBTQI Prisoners, which attempts to address the abuse of LGBTQ+ prisoners in the Commonwealth, such efforts are often ad hoc and poorly conceived, exacerbating conditions for those they are purportedly trying to help.

The commission visited MCI-Shirley in late 2019 and early 2020 to investigate the fallout from Freddy’s suicide, as well as the housing and medical issues that Randy, Richard, F., and others had been experiencing. Officers reportedly printed sign-up sheets for commission interviews on neon green paper, ensuring that the names of participants would be well known. The sheets were soon defaced with homophobic remarks. Richard reported that these sheets were authorized by then-Superintendent Kimberly Lincoln, who has since been reassigned to NCCI-Gardner.

There were also reports of officers using other tactics to publicly out participants in the commission interviews. One sergeant from the Inner Perimeter Security team, a class of guards who serve as investigators, was said to have used a letter that Freddy wrote before his death to out Edward. It was this incident that later led to Edward being beaten.

In early February, after the two visits from the commission, Randy wrote a letter to Gaffney, the deputy commissioner of the DOC. He explained that the commission’s efforts to shed light on certain issues may have done more harm than good.“The level of homophobia actually increased,” he pointed out. “It seems like the two LGBTQ Commission visits have put us all in an unfavorable light.”

Cox, the Black and Pink Massachusetts executive director, serves on the LGBTQI commision, and has said there is a conflict of interest in Gaffney serving as the DOC deputy commissioner and as a member of the safety commision. Furthermore, advocates say that dual role is a factor in the commission’s inability to protect LGBTQ+ prisoners.

“While I do think the DOC should have a seat at the table,” Cox said, “[it] feels like a conflict of interest, as she is employed by the very agency we are tasked with investigating. She has attempted to narrow the scope of our work [and] has also interrupted DOC staff to silence them or coax particular answers out of them.”

Struggling for self-advocacy

Amid criticism of Gaffney’s apparent conflict of interest as chair, the commission appointed a co-chair, Pam Klein, in the Spring of 2019. But LGBTQ+ individuals express increasing frustration at the apparent inability to prompt decisive change. Most have taken steps to advocate for themselves, though progress is slow and halting.

For Randy, the solution is simple. His Feb. 4 letter to Gaffney emphasized a clear and straightforward response to the litany of concerns expressed by LGBTQ+ prisoners at MCI-Shirley: lateral transfers for all LGBTQ+ inmates to MCI-Norfolk or NCCI-Gardner, both of which are prisons with larger LGBTQ+ populations.

Richard agreed: “If the DOC refuses to [transfer] us, then the openly LGBTQ+ inmates should be given permanent single-cell status. It would mean we don’t have to worry about getting gaybashed by a homophobic cellmate, or getting sexually harassed or assaulted.”

At the time of this reporting, Gaffney’s only response to letters from Richard, F., and four others who have written to her were to inform them that “formal inquir[ies]” have been opened into their cases. There do not appear to be lateral transfers in the works. Randy had a classification hearing early this year, and his request to be moved was denied.

Randy filed his suit against MCI-Shirley in November 2019, seeking redress under the First and Eighth Amendments for violations of his constitutional and state-specific rights. Richard has been working on his own case for some time, and F. has recently been in touch with Prisoner’s Legal Services. However, it has proven tough to work toward accountability within the prison environment. For example, Richard reported that many of the supporting documents he has collected, which mark a paper trail of abuse, have mysteriously “grown legs” and disappeared from his cell after routine checks by guards.

Fighting back

Randy, Richard, and F. have faced roadblocks at every level: internal reporting mechanisms have failed them, public efforts by the commission have only exacerbated the violence they experience, and establishing grounds for a civil suit against the prison can feel like a shout into the void. What’s more, the levels of hypervigilance and fear that prison culture instills in everyone—especially LGBTQ+ folks—renders even daily existence exhausting.

“The culture within the DOC and within most prisons is harsh and cruel—it’s an environment where incarcerated people live at the mercy of corrections officers,” said Tenneriello of Prisoners’ Legal Services. “But for LGBTQ+ people, it’s that much worse, because the culture is so homophobic. There is no doubt about the animosity that many officers bear.”

“Fundamentally, the problem that we’re facing is that our carceral system is punitive, and only punitive,” Sabadosa explained. “Until we change that, we’re going to continue to see [these] issues. [We need] to truly alter the culture that put all of those things in place.”

Even in the face of these challenges, Tenneriello firmly believes progress is being made by abolitionists and activists within the LGBTQ+ community, both inside and outside the walls of MCI-Shirley.

“LGBTQ+ incarcerated people are asserting their rights and getting necessary changes to happen, but beyond that, it’s a real challenge to prison culture as a whole,” she explains. “It’s a dehumanizing, macho culture—it’s not oriented toward the needs of any one individual. I think the struggle is spearheading the larger movement for respect and healing. What do people need to become their best selves? That’s what we should want for everyone who’s incarcerated.”

As F. wrote to me in an email: “I am a human being and deserve to be treated as such.”

This article was produced in collaboration with the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism.