To be concise, the reception consisted of two separate exhibitions hosted at the MIT List Visual Arts Center.

The first was Christine Sun Kim’s Off The Charts. The second being a collaborative installation titled Colored People Time: Mundane Futures, Quotidian Pasts, and Banal Presents.

As is the nature of art, the nature of display, and the carving of temporal space that’s completed through the act of admiration, both these exhibits present us with a heightened focus of our temporary spaces. Perhaps even in alarm, these works seek to prod us on varying versions of ownership as it pertains to space and place. Whether these spaces take shape physically, culturally, or linguistically, we’re brought to question the impact of sharing and distorting them.

I’ve made the editorial decision to detail these as one piece. It will be lengthy but I surmise there are some thoughtful outtakes we ought to consider. Those of which will only surface in the presence of a consecutive retrospection.

—

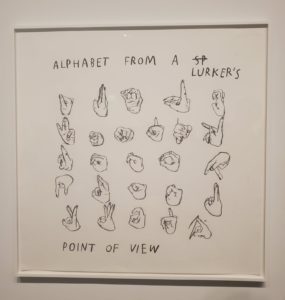

Past a pair of looming glass doors, Off The Charts sat in the right gallery. The room was packed with the average Cambridge youth but it was peculiarly quiet. More people than I had ever seen were speaking ASL. It was a safe space for the deaf community and I say this because of their minority statue. At a first glance, the span of Christine Sun Kim’s work seeks to create a multi-sensory phenomenon. The exhibit prefixes that this is an attempt to address the politics of language and sound-based interaction. I began to take note of the inequality that is created through the weight of voice.

It’s hard to imagine what day to day life would be without our voices. It feels alien to think about but that’s the exact distinction Kim challenges us to throw out the window. She pushes us to erase linguistic hierarchies “…troubling throughout conceptions of sound as being inextricably tethered to hearing and the implicit authority of spoken over signed language”. Hailing from California, Kim works in a variety of performative mediums including sound, drawing, and video.

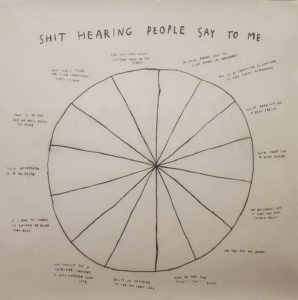

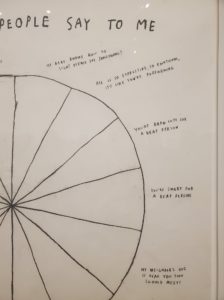

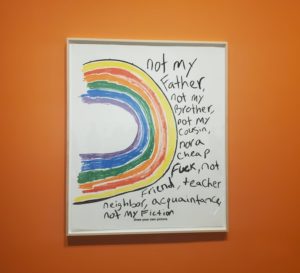

Off The Charts is presented and displayed meticulously. Upon entering, the gallery is starkly blank and I was gradually corralled into space. Upon all four walls are large canvas posters of Kim’s witty analyses of her experience as a deaf woman as well as a humorous outlook on society’s view of her. Her work breaks the barrier of vocality. It also empowers the deaf community by poking at our insecurities, our frazzled encounters, and by giving value to the privileges of being deaf. The exhibit uplifts the deaf experience by making it visible (and audible). It’s existence politicizes the nature of spoken word and the way that inequality is rooted in communication. Kim’s work speaks for itself.

The inner circle of the exhibit consists of a platform of cushions where you can sit down and listen to Lullabies For Roux (2018). In this second piece, Kim commissioned a group of her friends to produce lullabies for her daughter, Roux. These audio loops omit spoken words and instead focus on tonal frequencies. For her daughter, raised trilingually (ASL, German Sign Language (DSL), and German), these low reverberating lullabies represent Kim’s ascribed “sound diet” that seeks to place equal weight on all three languages. The very nature of sitting in the middle of the room with pairs of headphones sprawled around is isolating. As is the act of listening to music in headphones, you can block out the rest of the exhibit and have time to contemplate on the sound and frequency. Each lullaby varies in tone and pattern with almost no noticeable beginning or end. The looping nature of the tracks allows you to sink into them and appreciate the concept of sound stripped of level.

Although these lullabies don’t entirely escape the symbolic order, they begin to unveil different shades of notions represented in sound. You’ll have to visit the gallery to listen to these gems.

—

I can’t help but to take note on the multi-faceted theme of circularity: the pattern that the gallery itself guides you upon, the visual architecture of Kim’s graph’s (imperfect but intertwined), and the circular nature of conversing with another. One cycle lends itself to another. That alone seems to birth the conception of communication and understanding at its core. I think it’s this idea of equality and flow that uplifts the gallery. It’s the notion that we’re all interconnected despite the imbalances that society places on sound. It’s only when we begin to think about language purely as the paper airplane that transports our thoughts (although, yes, certainly integrated), that we’re able to break down defining cultural moments that have been sealed with pen in hand.

And I know that last sentence was vague but seeing Colored People Time directly after Kim’s exhibit allowed me to process the cultural and temporal weight that language pulls. In fact, I suggest viewing them in this order. Colored People Time acts as a guide for ways that language has equipped some of our most daunting systemic treacheries.

—

Let’s dig in here, dear reader, because Colored People Time wastes no time in exploring the profundity of spaces distorted by tools of racism and colonialism. It attempts to do this in a three chaptered exhibit: Mundane Futures, Quotidian Pasts, and Banal Presents. The entire exhibit is laid about in bite sized food for thought. There’s a lot to take in and a lot of connecting the dots that seems necessary but nonetheless, it’s a sequential exhibit and for that we must start in the first room.

Mundane Futures

The centerpiece of this first chapter begins with ‘The Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto’ which lays out the moral framework of afrofuturism as it stands today, hindered by history, and imagining their future. This room seems to represent the grit, the struggle, and the stories that unite those oppressed.

“A new focus on black humanity: our science, technology, culture, politics, religions, individuality, needs, dreams, hopes, and failings.

The awakening bedazzlement and wonder that awaits us as we contemplate our own cosmology of blackness and what will happen to black people over time.

The relief of focusing on what science and history tells us is likely, with emphasis on our cultural multivalence. The relief will come from a sense of being true, not from a rigid adherence to white validation.”

This manifesto covers an entire gallery wall and invites visitors to immerse themselves in the demands at the heart of Afrofuturism. As much as this first piece sticks a nail and thread point for the entire exhibition, much of it is a question. This group of Afrofuturists are saying, ‘okay, this is where we are now. This is who we’ve been carved into.’ And although a clean lens is placed on introducing black identities into the majority, there’s also a sense of uncertainty. As if it’s up to blackness to prove itself, it is up to others to acknowledge these mercurial transformations.

The rest of the room is filled with a variety of historical narrative pieces that each represent a chunk of the space that Afrofuturists feel they presently fulfill.

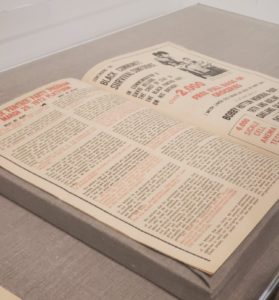

Quotidian Pasts

The second piece speaks mainly to displacement and how physical displacement is tied to emotional deterioration. Gallery pieces detail commonplace stories of forced diaspora and of the devaluing of land occupied by people of color. One immediately thinks of colonialism and this continual cycle of othering but these are all quotidian events. The exploitation of slavery and racism “…not only shaped the foundations of our country but exists in our present moment and impacts our future”. The act of disturbing black communities is presented as a haunting presence. We have not grown as much as we’d like to think.

It’s here that we can take a step back to circularity, about the fluid concept of time, and, of course, about colored people time. Here’s the internet’s official description of the term:

“Colored people’s time is an American expression referring to a negative stereotype of African Americans as frequently being late. The expression is often described as a derogatory racist stereotype. It is considered derogatory because it implies that African Americans have a relaxed or indifferent view of work ethic, which leads to them being labeled as lazy or unreliable.”

The exhibit explores the malleability of time as a concept through historical events that represent present day devastation. It aims to sprout new narratives about the experience of being black in America and shows that movements like Black Lives Matter isn’t just a target board floating in space. We can measure success but to be able to understand the damaged flow of living done to black and brown bodies, we must honor it an entire discourse that withholds the test of punctuality. The damage we’ve done and the efforts it will take to improve are forever ongoing. It is timelessly irreparable.

Banal Presents

Sitting in the near back of the gallery was the last piece of the puzzle and perhaps my favorite. It’s vital not just that we’re creating art and seeing art from under-represented cultures, but that those works are correctly represented. The display of art offers another window into the concept of time. Think about the way art is recycled, sold, re-displayed, often across hundreds of years. This last stage of the exhibit displays a conversation between artists Carolyn Lazard, Cameron Rowland, and Sable Elyse Smith. Each artist takes their own approach in examining the “…repercussions of chattel slavery with a focus on property, reparations, and the medical industrial and prison-industrial complexes”. It’s in daily life that systemic oppression endures and in the present moment where there lies the surface for critical intervention.

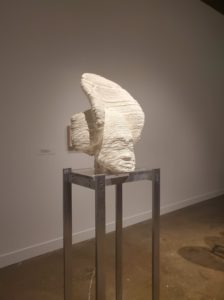

This exhibit’s main piece presented 3D printed re-created statues of figureheads from Penn’s Museum’s African Collection. In that, they are imperfect, squabbly, and lack the prestige that their placement in a top museum would place upon them. The idea here is that there exists an inherent violation of culture, of time, and of space by bringing these artifacts into a museum. Through displacement of space and the disfigurement of time, Colored People Time becomes a collective rebuttal of capitalism’s fist. In the banal present, the space yet to be bent any further, there’s space to act.

—

The artists in these three chapters attempt to characterize and infringe upon their entanglement with those who, and who have, sought to conquer their future. It’s here we see how dominant the privileged enforce efficiency in the name of capitalist production. They define it as a “collective performance of refusal: A refusal to disavow our embodied sense of time, beyond capital’s demands. A refusal to accept that history occurs, and remains, in the past. A refusal to adhere to Western time as the only time.”

In succession, we dig deeper into the trenches of injustice and begin to understand how a country with an endless history of slavery, of colonialism, and of a dysfunction of power translates into the present. Every aspect, from the way we talk down to people, or don’t try to communicate at all, to the valuation of other culture’s artifacts, to the weight of their space occupied, distorts the self. Within communities that have suffered the dis-figuration of temporal space, of physical land, and of language, we’re pleaded to think in the present and to allow them, in their refusal of history, to carve out the next piece of the future.

—

Both of these superb exhibitions are at the MIT List Visual Arts Center and showing until April, 12th 2020. I highly suggest taking time to view them both.

Christine Sun Kim: Off The Charts