William Lyon Mackenzie King (1874-1950) served as prime minister of Canada from 1926 to 1930, and again from 1935 to 1948. Despite his coldness and lack of charisma, King ascended to the top ranks of the Liberal Party to become one of Canada’s most revered leaders. Through shrewd diplomacy and an even hand, King shepherded the country through World War II, helped calm the contentious relationship between English and French populations, and ushered Canada into the modern technological age. He never married, and while historians have speculated that he may have been gay, evidence would seem to indicate that he simply wasn’t a very interesting person. He died at age 75 in 1950, less than two years after leaving office.

I know all of this because I just finished perusing King’s entries on Wikipedia and Britannica.com. I very pointedly did not learn this from The Twentieth Century, the new feature-length portrait of Mackenzie King from Winnipeg-based experimental filmmaker Matthew Rankin. To say that The Twentieth Century is not a conventional biopic would be an understatement. Nor is it some Hamilton-style attempt to update and millennialize an ostensibly stuffy historical figure. To be honest, I’m not sure I could tell you what the hell The Twentieth Century is. All I know is that it’s one of the strangest, most delightfully baffling films I’ve seen in years, and I can’t recommend it enough.

In Rankin’s telling, Mackenzie King (Dan Beirne) is a wide-eyed naif whose one goal in life is to win the Prime Minister Competition (a sort of mini-Olympics featuring such Canada-centric events as waiting your turn in line, identifying various trees by scent, and clubbing baby seals). One day, while reading to a tubercular young girl in the Home for Defective Children, he falls head over heels for the beautiful Ruby Elliott (Catherine Saint-Laurent), who plays her harp to soothe the patients (King has never heard music before, and consistently misidentifies the harp as a trumpet). Ruby, you see, bears a striking resemblance to King’s True Love, as depicted in a painting dictated from a vision by his oppressive, bed-ridden mother (Louis Negan, playing the role like something of a cross between Ernest Borgnine and Frank Booth, but in a Goldilocks wig). Ruby is also the daughter of the tyrannical Lord Muto (Seán Cullen), the iron-fisted ruler of Canada. When Ruby ships off to fight the Boers overseas, King spirals into depravity and boot-fetishism, leading him to the cruel treatment of the anti-onanistic Dr. Milton Wakefield (Kee Chan). Back on his feet, King seeks Muto’s good graces, and eventually leads the charge in an ice skating battle against ornithologist J. Israel Tarte (Annie St-Pierre) and his legions of moon-eyed followers to see whose flag will replace Canada’s current banner, the Disappointment.

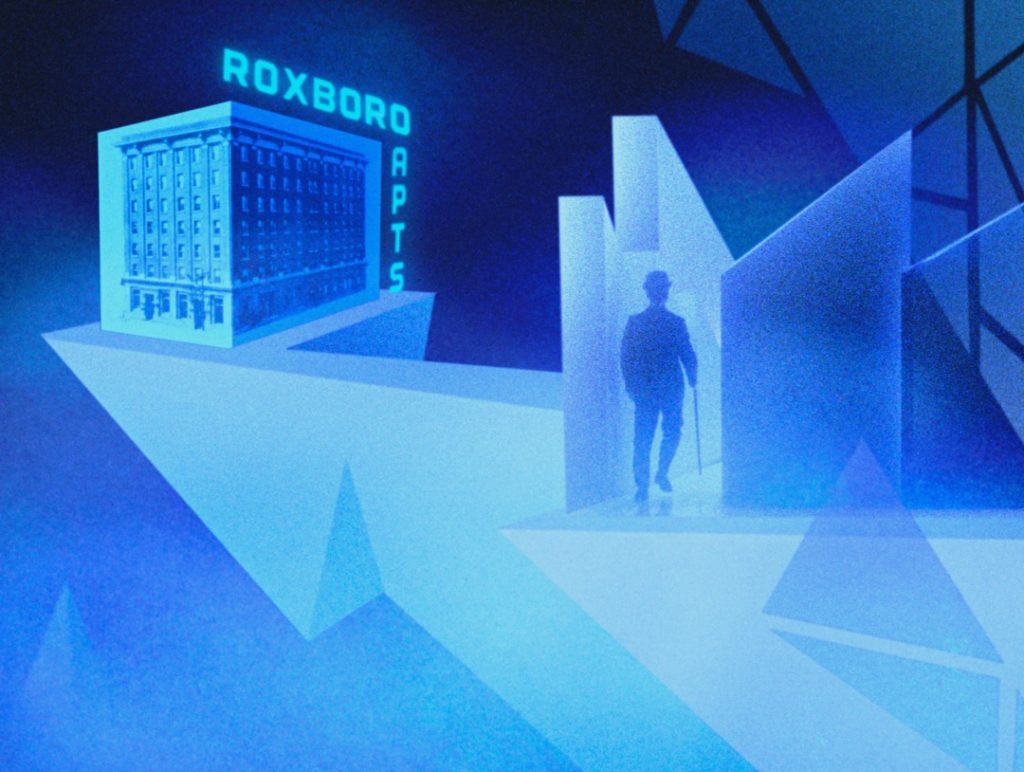

Something I’ve realized as a critic and film fan who gravitates toward lower budgets is that it’s better to create your own visual language than to emulate the status quo; one of the easiest and worst mistakes an independent filmmaker can make is to try to recreate a “real” Hollywood movie. To put it lightly, this is not a mistake that Matthew Rankin makes. The Twentieth Century clearly draws inspiration from the early Technicolor films of the 1930s and ‘40s (particularly such obscure two-strip oddities as King of Jazz), but it synthesizes these elements into something wholly unique. Shot entirely on a soundstage against eye-popping colors and composites, Rankin’s Canada is a giddy, expressionistic fever dream– imagine if Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger were fond of sniffing airplane glue, and you’ll be in the right ballpark. Travel sequences are represented by paper cut-outs gliding between rough drawings and Xeroxed photographs; later, when King boards a ship, the ocean is represented by a large tarp being waved behind him. Some filmmakers strain against a low budget; Rankin flourishes.

Camp is obviously a key word here, from the MGM-via-thrift-shop aesthetic to the performances, which bend genders in every direction imaginable. But this isn’t camp for camp’s sake, which can be exhausting. Rather, Rankin’s strain of camp is of a personal, deeply weird variety more akin to early John Waters or fellow Winnipegger Guy Maddin (seriously, what is going on in Winnipeg?). The tone is tongue-in-cheek to the extreme, but there’s never a sense that the film is winking to the camera. Cameras are, after all, a human invention from planet Earth. The Twentieth Century feels like it was beamed in from Mars, or the Black Lodge, or some obscure dimension that exists perpetually in the transition between vaudeville and talkies. Watching it feels a little bit like being Jodie Foster in Contact, trying to decipher signals from a faraway galaxy.

Of course, where it actually comes from is a planet called “Canada,” which perhaps puts me at a disadvantage from a critical standpoint. I have no idea how recognizable a namedrop William Lyon Mackenzie King is in the Great White North, but I got the distinct impression while watching that there were layers of satire flying over my toque-less head. Did this hinder my enjoyment? Not really; Rankin’s depiction of Winnipeg as a trash-strewn den of iniquity populated by tutu-wearing heroin dealers and casually profane children is hilarious whether or not you’ve ever been there, and it’s possible a lack of context simply amplifies the intentional bewilderment of it all. Still, I’d be curious to hear how differently this film might be interpreted by someone more well-versed in can-con.

That said, I can’t imagine all the context in the world would make The Twentieth Century any less of a delightful mindfuck. As with any film so dedicated to its own internal language of kitsch, your tolerance will likely depend on how attuned you are to Rankin’s wavelength; if you’re not hooked in the first five minutes by its strange charms, you’re probably going to be in for a long slog. Personally, however, I couldn’t get enough of it. Even if I didn’t understand all of what I was seeing– could anyone?– I watched the entire thing with my mouth agape in a joyful smile. Like such junkyard fantasias as Forbidden Zone and The American Astronaut, The Twentieth Century is likely to garner Rankin a devoted cult base– and, just maybe, inspire a wave of interest in Canadian parliamentary history.

The Twentieth Century

2019

dir. Matthew Rankin

90 min.

Available to rent via the Coolidge Corner Theatre or Brattle Theatre virtual screening rooms

Right now Boston’s most beloved theaters need your help to survive. If you have the means, the Hassle strongly recommends making a donation, purchasing a gift card, or becoming a member at the Brattle Theatre, Coolidge Corner Theatre, and/or the Somerville Theatre. Keep film alive, y’all.