I remember walking out of the theater from Iron Man (2008) as a child, pushing the tips of my fingers to their extremes in order to generate that weird tingling feeling. The gesture itself looked more Emperor Palpatine than it did Tony Stark, but by some dumb childish logic, that weird finger-tingling thing made me feel like I could be a superhero.

Walking out of The Majestic 7’s 7:00 PM premiere of Shin Ultraman, I saw an elderly Asian woman doing the Ultraman equivalent viz-a-viz his iconic cross-arm pose as she entered the parking lot, just in front of the Home Depot. The people she attended with laughed with her, but there was something wondrously committed about her pose—bent knees, unassuming, without winking, for the simple purpose of making another human smile.

And that’s also how I’d describe Shin Ultraman: it’s a movie that really adores humanity and just wants to entertain us humans. It’s not “escapist,” though I’m not sure that word actually means anything. That’s what Shinji Higuchi’s movie is all about. Like, it loves humans and wants to forefront the things that distinguish us from our fellow animal friends: our capacity for love, the ability to make moral decisions, and especially our ability to reckon with death. It’s a cheesy utilitarian tokusatsu with shades of The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951;2008), Jack Kirby, and anime—and if that combination doesn’t describe the degree to which Shin Ultraman is completely satiated with the acute peculiarities of our species, well, then you just need to see the film for yourself. Actually, you just need to see it full-stop.

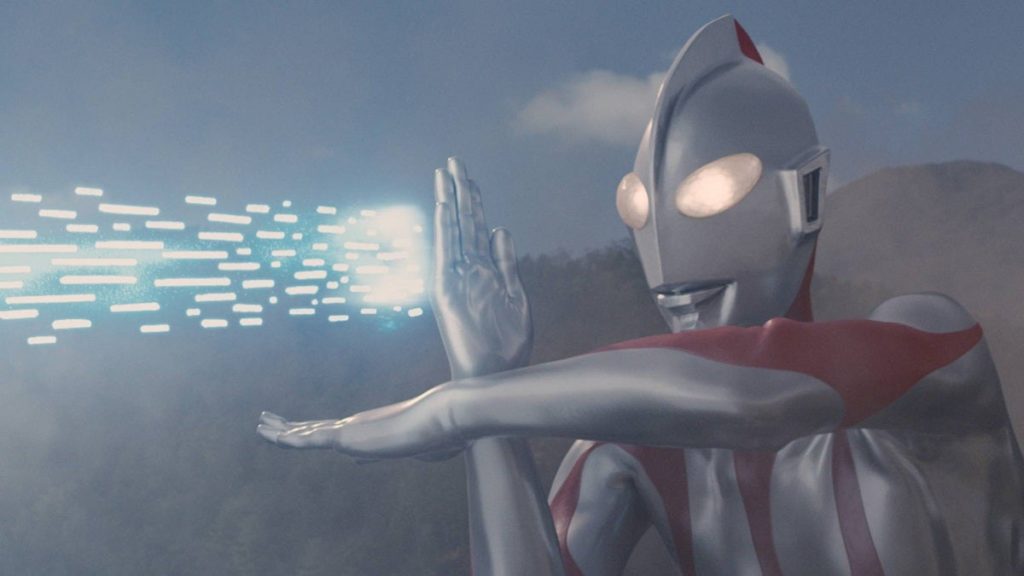

For the uninitiated, a series of monsters called kaiju have been intermittently showing up in Japan (and only Japan) for some time now, destroying cities and killing civilians. When the rhino-dragon-looking Neronga attacks an unnamed town, a 60-meter-tall alien that looks like a Power Ranger shows up and uses his hands to make an energy beam not entirely unlike the force (his “spacium beam”) that he then uses to destroy the kaiju. He chooses to become Earth’s dedicated protector after witnessing a government official, Shinji Kaminaga (Takumi Saitoh), sacrifice his life to save a child from the ensuing destruction—but, in direct conflict with the Code of the Planet of Light, he merges his being with this dying human, sharing his body when he’s not in Ultraman form.

Avoiding spoilers, it’s enough to say that fate of Earth ultimately rests not in Ultraman’s enormous hands but in the ability of humanity, or more accurately, the Japanese government, to respond to a new, extraterrestrial and xenocidal threat. Even with the unavoidable nationalistic tenor of these sorts of movies, it’s done so well—and is personalized through a small specialized team at the S-Class Species Suppression Protocol (SSSP) task force—that it feels less like Independence Day (1996) than it does Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979). All things considered, it’s probably a good thing for humanity that the kaiju didn’t spawn in the less capable United States.

It’s also expertly directed by Higuchi, though the auteur of note is the essentially omnific writer, producer, and editor Hideaki Anno (Neon Genesis Evangelion, Shin Godzilla). I didn’t think a superhero movie could feature such auteurist and even experimental cinematography. If you’ve ever seen Anno’s early live-action digital work in the disturbing anti-voyeuristic Love & Pop (1998), you know exactly what I mean. The camera is put in angles you’ve never seen before, at least not in a superhero movie. In one shot, the camera looks up at a member of the SSSP from the inside of a bag of chips. In another, it looks up at two men on a public park swing from an angle so obtuse that the men become almost indistinguishable.

What’s the point of all this anti-realism? I’m not really sure. Following Love & Pop, a coming-of-age film about teenage girls ensnared in “compensated dating,” the style is an apparent mismatch for the kaiju film, at least at first. There is something still voyeuristic still, in which the response of humanity to an extraterrestrial crisis must be observed and subsequently saved or damned based not on the effectiveness of their response but rather how they chose to respond or not. Regardless of the intended reason or even if it’s a stylistic miss, the originality added to the Blue Beam genre makes me smile, just like that woman in the parking lot leaving the Majestic 7.

Shin Ultraman

2022

dir. Shinji Higuchi

112 min.

Screened Wednesday, 1/11 in select theaters via Fathom Events

Coming to VOD, blu-ray, and DVD in spring 2023