American history is a little like Santa Claus. When you’re young, you tend to learn the rosiest possible version: Washington and Lincoln, the pilgrims and the Declaration of Independence, and the general vision of life and liberty. Then, later– likely either high school or college, depending on the progressiveness of your hometown– you start to fill in some of the ickier gaps: slavery, Nixon, the systematic genocide of indigenous peoples. Yet even at this juncture, there are a handful of historical avenues so sordid that you may not find about them until later, and they may elicit gasps from even the most world-weary adult. It is in this squarely in this category that we find the FBI’s years-long campaign to discredit and destroy Martin Luther King, Jr., who they considered to be “the most dangerous Negro in America.”

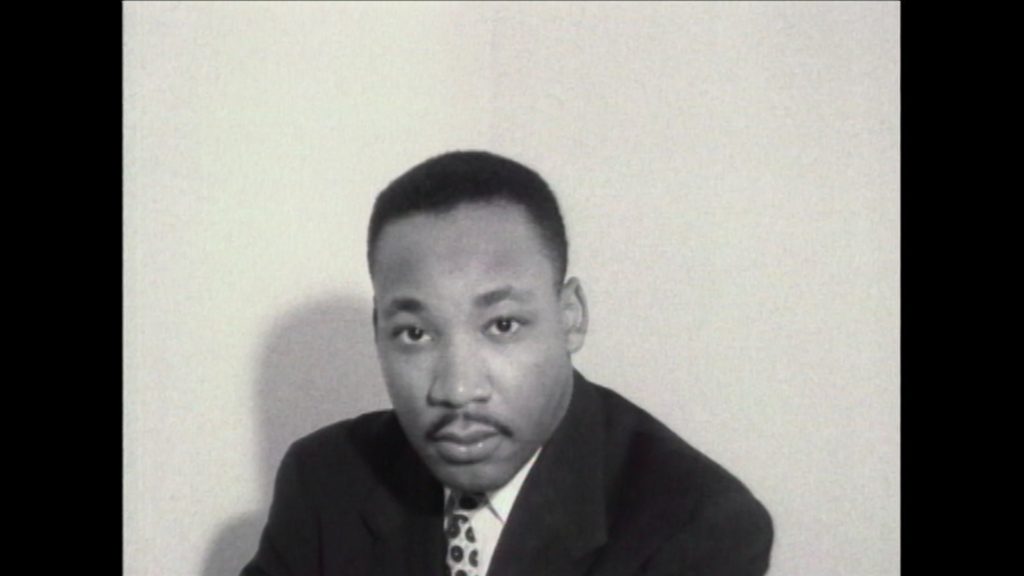

This story is laid out in truly startling detail in MLK/FBI, the sobering new film from documentarian Sam Pollard. Through voice-over testimonials from historians and civil rights contemporaries, as well as a mountain of archival footage, Pollard explicates a comprehensive timeline that proves that no American institution can ever be as spotless as textbooks make them out to be– no matter how much it hurts to learn.

The campaign had its roots in the McCarthy-era ferreting out of supposed communist subversion in America, which, with depressing reliability, would be most often “found” in minority populations (consider that the other most targeted group tended to be Jewish screenwriters). In this search, Hoover’s eye landed on Stanley Levison, a white, Jewish lawyer who served as one of King’s closest advisors. Working under the dubious assumption that African Americans would be more susceptible to communist influence than whites, the FBI began tapping King’s phone and surveilling his hotel rooms, and began compiling a profile that painted him as a womanizer and sexual deviant. How much of this incriminating evidence was factual and how much was embellished remains a topic of debate, but it’s ultimately beside the point, which is that the United States government has always been, and continues to be, capable of cartoonishly awful shit.

Pollard’s background is in editing, including a jaw-droppingly run in the ‘90s of films for Spike Lee and Ernest R. Dickerson. MLK/FBI is nothing if not a feat of editing; until the film’s final moments, Pollard’s interview subjects remain voices in the ether, hovering over deftly assembled newsreel footage and TV interviews with King (there is, understandably, little actual contemporaneous footage of the FBI itself, which Pollard represents via cheekily deployed clips from movies like I Was a Communist for the FBI). The result is almost like animation, with disparate bits of footage woven together to form a narrative as cohesive as any biopic. There are acknowledged blank spaces, of course, but there’s enough hard evidence– including the notorious letter the bureau sent to King encouraging him to kill himself– to get a pretty clear idea of how deep and rancid the campaign was.

But perhaps the most mind-blowing thing about the film is the reminder of how much of the FBI’s work was already done for them. J. Edgar Hoover is today remembered as something of a notorious 20th-century bogeyman thanks to decades of truth-is-out-there conspiracy lit, but it’s easy to forget that he was, at his peak, one of the most trusted men in America. As an FBI historian tells in the film, Hoover was remarkably media-savvy, personally recruiting agents to match his ideal G-man aesthetic: square-jawed, dark hair, imposing build, snappy dresser. In a mind-blowing statistic, a poll taken at the height of the campaign revealed that fully fifty percent of Americans sided with Hoover, and only low double-digits with King. History may be written by the winners, but the present tends to be written by the creeps.

Then there’s the troubling matter of the insinuations themselves. As awful as the FBI’s campaign was, there seems to be little doubt that they found something. By all accounts, King was indeed something of a womanizer, and if the most torrid elements of the dossier are true, he may have been something a few degrees worse. In the film’s arresting finale, Pollard brings his previously unseen talking heads on camera and asks them what they feel their responsibilities are as historians when dealing with a figure like King, and most of them are understandably uncertain how to answer. To be sure, no revelation could ever undo the profound good he did on this earth, but as humans, it’s difficult to fully wrap one’s head around what it would do to our perception of the man if Hoover’s apparently extant tapes saw the light of day. This is not a hypothetical, either: due to a 1977 court order, the tapes may enter the public domain as early as 2027. What will happen as we hurtle toward that date is one of the film’s most ominous mysteries.

There is a tendency to believe that things right now are worse than they’ve ever been, that our current political discord is thanks to the recent machinations of social media and Fox News and the Current Occupant of the Oval Office. There is also an inclination, instilled in most of us since childhood, to view the problems of the past as just that. The reality, of course, is that it’s always been bad. The government has always been, and will continue to be, filled with self-serving monsters and vindictive finks, and even the best among us may be revealed to harbor dark secrets. The FBI’s campaign against Martin Luther King didn’t end because they were satisfied, or because J. Edgar Hoover learned the error of his ways, or because a brave whistleblower stood up to them; it ended because King died*. Had tragedy not befallen him, and had the government’s campaign continued unabated, who knows what might have been revealed and what damage may have been wrought? The FBI’s case against King defies easy answers, and it’s not easy to wrap one’s head around. What Pollard does, and does very well, is lay out the facts as plainly as possible, and leave it to us to consider the ramifications. Ultimately, it’s a reminder that the bad will never abate– and that the good can never stop fighting.

* – Pollard doesn’t travel too deeply down the rabbit hole of James Earl Ray’s connections, but it is abundantly clear that, at the very least, the FBI knew enough that they probably could have stopped them.

MLK/FBI

2020

dir. Sam Pollard

104 min.

Available digitally via the New York Film Festival from 8:00pm Monday, 9/21, through 8:00pm Saturday, 9/26

Follow our continuing coverage of the New York Film Festival here!

Right now Boston’s most beloved theaters need your help to survive. If you have the means, the Hassle strongly recommends making a donation, purchasing a gift card, or becoming a member at the Brattle Theatre, Coolidge Corner Theatre, and/or the Somerville Theatre. Keep film alive, y’all.