As I take a picture of Revere’s gritty, faded Ocean Plaza storefront, which blends into Angkor Thom Market, an older Moroccan man strikes a pose and says with a big smile “Yes, take my picture please!” I laugh and ask if he speaks Shilha, Riffian, or another Amazigh language. Boston (specifically East Boston and the surrounding areas) has the largest Amazigh community in the US. Rapid new settlements along the Blue Line are erasing these communities, stop by stop.

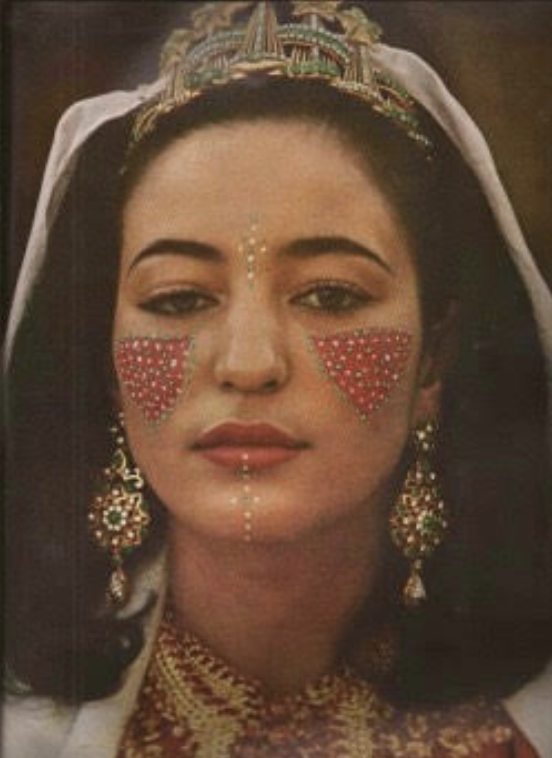

Famous for their resistance against Arab and Islamic colonialism, the Amazigh people are the Indigenous people of North Africa (Tamazgha). They have tattoos demarcating their tribal affiliation and follow pre-Islamic spiritual traditions worshiping the Earth, sun, mountains, astrological formations, and the Tamazight language itself.

Famous Amazigh musician and revolutionary Lounes Matoub boldly proclaimed, “I said no! I played hooky in all my Arabic classes. Every class that I missed was an act of resistance, a slice of liberty conquered. My rejection was voluntary and purposeful.”

At a Yennayer (Amazigh New Year) celebration in Somerville, when asked about Lounes Matoub, a young man exclaims “he is our hero.”

Land theft, chemical warfare, incarceration, forced conversion, environmental destruction, ethnic cleansing, language loss, and surveillance are regular features of Arabization and Islamization faced by Indigenous people throughout the Arab and Muslim world.

The Boston area is also home to large populations of Kurds, Assyrians, Copts, Mizrahi Jews, and Baháʼís, all of whom have suffered various forms of the same imperialism as Amazigh people. Mayans, Tibetans, Afro-Brazilians, Haitians, and Cape Verdeans also call Boston home, along with Native Americans (mostly concentrated in Mashpee, Massachusetts), who were the first displaced peoples on this land, and members of the Black diaspora who were displaced from their homes in west Africa.

What does it mean to displace the already displaced, those who come here with a legacy of displacement in their own homelands?

Amazigh activist Nuunja Kahina writes:

“We may be able to piece together fragments – names and stories of deities – from various regions of Tamazgha… Islamization and Arabization have worked hard to eradicate the spiritual history of Tamazgha.

As in much of the colonized world, religion was and is used as a tool of Arab colonization in North Africa, allowing for the destruction of Indigenous language and culture.

Mother tongue [is considered] to be of highly spiritual, and even sacred, significance. The land, too, is sacred and conceptualized in the political Amazigh imagination as Tamazgha, a region transcending the borders of modern nation-states. This is a re-Indigenized spirituality, not developed by ‘going back’ and looking at pre-colonial religious beliefs, but by constructing the present material world around them as sacred.

How do you decolonize and return to your Indigenous spirituality if you don’t know what it is?

This land- and language-based spirituality, then, is still very much engaged with the natural world, but also re-inscribes a sacredness that was previously taken and destroyed by the influence of outside religions. Imazighen [plural of Amazigh] themselves are the creators of this spirituality, rather than being necessarily endowed by a divine being.

The Amazigh people have survived extended and repeated processes of colonialism and continue to live under and struggle against Arab domination in their homeland. The destruction of our culture and beliefs will never be undone, but as Amazigh resurgence movements demonstrate, we are not static or entirely dependent on the past.”

The Amazigh philosophy of being unable to reproduce a pre-colonial world, but to create with the reality around them, is the perfect metaphor for what refugees, migrants, and asylum seekers do when they come to Boston.

East Boston forms a unique nexus that plays several roles for the city and state as a whole. It serves of infrastructural importance as a port, its architecture and ambiance feels squeezed into a small land mass defined by its proximity to its ocean surroundings, and it serves as the epicenter of the Hispanic community.

The beloved neighborhood has been the subject of much media fascination and research projects with new settlement in the form of commercial and residential development harming local public schools, causing further concerns about ecological damage on reclaimed land prone to rising sea levels, and the fierce fight over the demarcation of space by locals and gentrifiers.

East Boston, Chelsea, Revere, and Lynn share many features of being historic places where the atmosphere and culture is greatly shaped by the urban coastal proximity, a long relationship with corrupt politicians and policing, and maintaining immigrant majorities. The images that dot my head when I think of riding the T or MBTA buses in any of these areas is of immigrant women who are essential workers, usually chatting in their mother tongues in groups of two or three.

Through all the coverage, these areas are seen as only Hispanic–separate from Latino, as these areas have particularly large Spanish-speaking populations whereas other parts of Boston and Massachusetts have Brazilian or Indigenous communities that speak native languages like K’iche.

In reality, Hispanics may form the largest group, but North Africans form a very significant second-largest demographic. People from countries like Morocco and Algeria are very much represented and part of the landscape- this ever-present reality is reflected in the languages in which local schools print their communications, and the many North African (especially Moroccan) establishments ranging from barber shops to pastry spots.

Including and examining both prominent communities of this largely coastal conglomerate of immigrant majority cities in our discussions is not only vital, but an honest portrayal of the stitchings that hold together the entire fabric. We know real-estate markets and developers prey upon these places as plots they can build on top of at the cost of who is already there. We can at least show everyone who these people are- what are their names, what are their stories, what are their traditions?

Boston aficionados are aware of the rich presence of North Africans and the glimmer they add to our worn streets. What many don’t know is many North Africans are not Arab, even though the dominant language is Arabic. If you ask your neighbors in your triple decker what languages they know, a lot of them will proudly cite an Indigenous language as their mother tongue. The city is teeming with Amazigh organizations and associations like the Amazigh Cultural Network in America (ACNA) and the Boston Amazigh Community (BAC). It is bubbling and bursting at the surface, awaiting at the corners of the mouth that tease out those unasked questions.

In between MBTA lines are pockets of these little worlds that come together. The immigrant is the greatest artist because from nothing, we create life.

@verifiedspicequeen where I post about fun, important, and unique topics!

See the original version of this story here.