In Cult Case Files, Hassle film editor Oscar Goff shines a light on cult classics of the distant past, the alternate present, and the possible future, and tries to get a bead on just what the words “cult classic” actually mean. To catch up with the rest of the series, click here.

What’s your favorite Dave Clark Five song?

Whether you have an answer to that likely depends directly upon your age. The Dave Clark Five were one of the major bands of the so-called British Invasion of the 1960s. They were among the first UK rock bands to follow the Beatles’ lead in touring the states, and had an astounding 17 US Top 40 singles between 1964 and 1967. By any estimation, they were every bit the cultural peers of the Stones, the Kinks, or any number of other beloved bands of the era. But Clark was also a shrewd businessman, who served as his own band’s manager and kept a tight hold on the rights to his recorded output. As a result of Clark’s possessiveness of his legacy, all 15 of the band’s albums fell out of print in the late ‘70s, and were never officially released on CD. Oldies stations stopped playing them– after all, why promote music that most people can’t purchase? The DC5 catalog was finally uploaded to iTunes in the late 2000s, but by that point they’d already been forgotten by two generations of music lovers. At the record store where I used to work, the only Dave Clark Five albums we carried were crudely pressed bootlegs. In nearly a decade, I don’t think I ever sold one to someone under 50.

I’m reminded of the strange case of Mr. Clark as movie consumption transitions fully into the world of the digital. At first glance, one might come to the conclusion that we are entering a new golden age of film accessibility– thousands of films, at your fingertips for a modest monthly fee, without having to so much as put on pants! But with every new format, the field seems to shrink: not every film was released on VHS, not everything on tape was transferred to DVD, and not everything on disc has been digitized for your enjoyment. And as loathe as we are to admit it, the canon at any given moment is largely dictated by availability– consider Alejandro Jodorowsky and Satyajit Ray, two titans of world cinema whose work was next to impossible to see for the first few decades of home video. What’s more, as we move away from physical media, we find ourselves increasingly limited to what is available at this very moment, with fewer and fewer opportunities to watch films whose distribution deals lapse, or who don’t command sufficient clicks to sate the algorithm. As a result, we run the risk of filmmakers– particularly independent filmmakers– whose work is in danger of falling into Dave Clarkian obscurity. And of these potentially lost legends, few names loom larger than that of Russ Meyer.

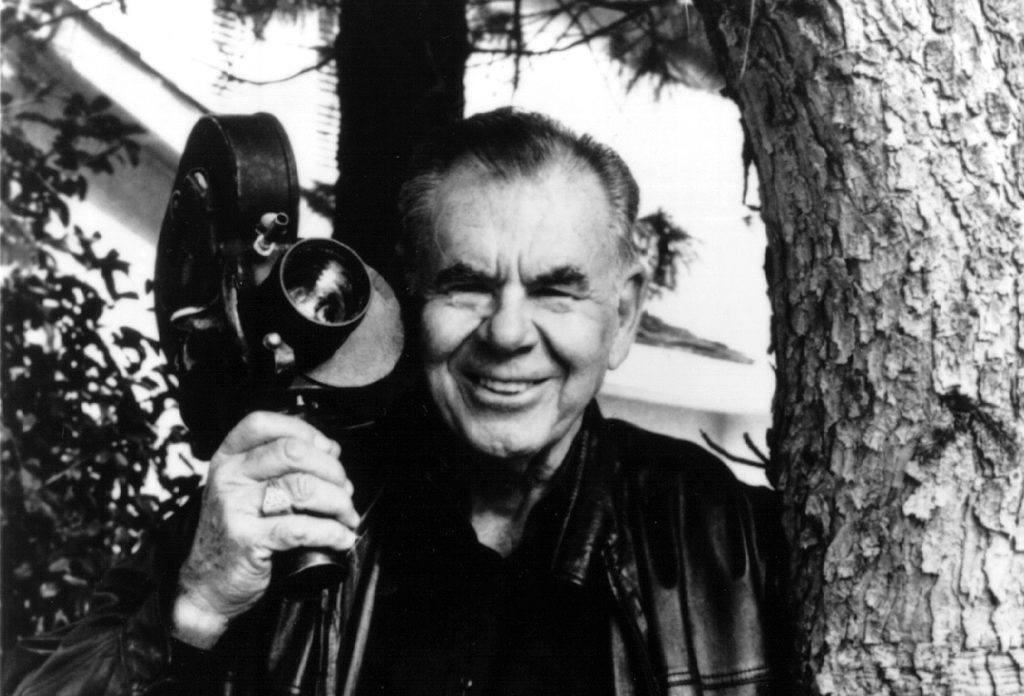

Russ Meyer was a pioneer in “sexploitation,” an oft-awkward strain of proto-softcore which filled the void between the fall of the Hays production code and the rise of porno-chic. But his reputation as “King of the Nudies” doesn’t quite do justice to the strange appeal of his work. Everything about Meyer’s films was exaggerated to a cartoonish, occasionally grotesque extent. This most famously applied to his lead actresses, who he cast with an eye toward their towering physiques and, uh, pendulous attributes. But even setting aside his distinctive leading ladies, Meyer’s films were unmistakable. His scripts (frequently written by critic and drinking buddy Roger Ebert) were filled with rapid-fire one-liners and strangely literate proclamations, like if Howard Hawks were asked to punch up a smutty version of Beowulf. His plots are simultaneously simplistic and operatic, playing more like a comic book than a live-action movie. And unlike most exploitation films of the day, which were shot with all the finesse of a driver’s license, Meyer’s films were eye-poppingly kinetic, shot in stark black and white or pop-art color and edited (usually by Meyer himself) with the staccato rhythms of a TV commercial. His films are so transfixingly weird that they can be enjoyed even if one has little interest in skin flicks.

Today, Meyer’s legacy largely rests on a pair of looming “designated classics”: Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! and Beyond the Valley of the Dolls. The former– a supercharged exploitation epic about a trio of drag-racing, judo-chopping go-go dancers on a murderous quest for desert treasure– is something of a riot grrrl ur-classic, with a densely quotable screenplay and an iconic performance by the towering, half-Japanese Tura Satana as leather-clad leader-of-the-pack Varla. Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (affectionately known as BVD), meanwhile, shows what Meyer could do with a budget. Hired by 20th Century Fox to fashion a sequel to their adaptation of the scandalous novel by Jacqueline Susann, Meyer and Ebert instead turned out a jaw-dropping, straight-faced parody of Hollywood melodramas. What begins as a nominal expose of Tinseltown leads to a gloriously transgressive climax involving lesbians dressed like Batman and Robin, decapitations via sword, and the beachside execution of escaped Nazi Martin Bormann. Perhaps improbably, BVD was a major hit for the studio, and instantly became enshrined as a countercultural favorite (the immortal line “This is my happening, and it freaks me out!” has been lifted by everyone from Enid Coleslaw to Austin Powers to The Fall). In many ways, BVD feels like the most fully realized version of Meyer’s uniquely pervy vision.

Yet, in one crucial aspect, it is an anomaly. Following a sour business deal early in his career, Meyer made a point of holding complete control over the distribution of his films. For many years, Fox’s handling of BVD bore him out: embarrassed by the film’s excesses, the studio kept it in the vault for decades, while Meyer kept the remainder of his catalogue in print on VHS and DVD via his own Bosomania imprint. However, the thing about one-man operations is that they’re dependent upon one man. Meyer died in 2004 at the age of 82 (teeing up one of my all-time favorite Onion gags), leaving Bosomania largely adrift. Physical copies of Meyer’s films– which were never exactly easy to find in conventional stores– became rarer and rarer, and began fetching higher and higher prices on the secondary market. The majority of his catalogue is unavailable for streaming, and, due to the explicit content of the films, can’t even be uploaded to Youtube. Ironically, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls is now the only Russ Meyer film one can easily purchase and watch– on a lavish, Criterion Collection blu-ray, no less.

Of course, there’s another reason why Meyer’s films might no longer retain the same cache they once did. Sexploitation, once a staple in the average cult film diet, is a little tougher to digest in the post-#MeToo era, its sleazy misogyny a little harder to overlook. Meyer’s films have aged somewhat better than most– his Amazonian heroines show real agency, and tower over their male counterparts both figuratively and literally– but he still represents a decidedly regressive strain of leering masculinity. His films are frequently dotted with sexual assault, as well as casual bloodshed, limp-wristed gay stereotypes, and an all-around commie-hating reactionary streak. If anything, it’s a testament to his reduced cultural footprint that we haven’t seen a rash of thinkpieces dissecting his work; if Russ Meyer isn’t “problematic,” I don’t know who is.

And yet, Meyer’s films are so outrageous and over-the-top that they approach a strange sort of innocence. Meyer was, of course, heterosexual– ragingly so– but his films are informed by such an undeniably intentional sense of camp that it’s difficult to imagine one approaching them out of sheerly prurient interests (not for nothing is John Waters an avowed superfan). Rather, Meyer’s films often play as a parody of sexuality, with their soap-opera plots and lascivious situations exaggerated beyond anything remotely resembling reality (take, for example, 1976’s Up!, which opens with a lengthy S&M session involving an elderly, suburb-dwelling Adolf Hitler). What’s more, Meyer approaches his films with a sense of earnestness and inventiveness and fun that’s truly rare in the genre, and infectious to boot. Meyer’s tombstone reads “KING OF THE NUDIES – I WAS GLAD TO DO IT.” Both halves of that epitaph are self-evident while watching his films.

So is the cult of Russ Meyer doomed to extinction? Perhaps not. By the time I came of age as a snotty, movie-obsessed teen, his films were already nearly impossible to come by in my suburban world of video rental stores (at least without crossing the forbidden Beaded Curtain). Yet Meyer’s films were still spoken of in hushed terms in the guidebooks and message boards that served as the foundation of my cinematic education. And that, ultimately, is the crux of the cult movie phenomenon. Cult films aren’t easy to find unless you seek them out, or someone guides you to them; that’s what cult movies are. The threat that streaming poses to film accessibility is very real, and will remain a source of concern to anyone with an interest in preservation for as long as the current system holds. But as long as there are diehard cinematic misfits dedicated to spreading the psychotronic gospel, oddball auteurs like Russ Meyer will remain.

WHERE TO WATCH: Well, that’s the whole thing, isn’t it? Beyond the Valley of the Dolls is readily available for rental on most digital platforms, and on the aforementioned Criterion disc (which features, among other priceless extras, a vintage commentary track by Ebert, a new interview with John Waters, and a 1988 British TV special in which Meyer offers a tour of his museum-like house). After that, things get spottier. You can probably find some of his less explicit work (such as Faster Pussycat) on Youtube, though these are obviously subject to takedown notices. If you find yourself sufficiently intrigued and have some leftover stimulus cash to burn, his films are easy enough to track down on DVD, albeit at inflated prices (if you have a region-free player, I recommend the UK releases, which bundle his films as double features and pad them with worthwhile extras). Beyond that, I don’t know where to send you other than the murky world of BitTorrent.

FURTHER STUDIES: As previously mentioned, there’s really never been a filmmaker like Russ Meyer. However, if you’re looking for more films at the intersection of tasteless sleaze and idiosyncratic outsider art, you may enjoy the work of Doris Wishman. Wishman’s work is more guileless than Meyer’s (she’s more commonly compared to Ed Wood), but her perspective is just as uniquely skewed; she was even invited to the Harvard Film Archive for a retrospective in 1994. She’s also undergoing something of a rediscovery at the moment, with her gutter-classic Bad Girls Go to Hell streaming on the Criterion Channel, a brand new LP/DVD set from Modern Harmonic, and a forthcoming blu-ray box set from Something Weird Video and the American Genre Film Archive. In other words, don’t be surprised if her profile soon eclipses Meyer’s.

Right now Boston’s most beloved theaters need your help to survive. If you have the means, the Hassle strongly recommends making a donation, purchasing a gift card, or becoming a member at the Brattle Theatre, Coolidge Corner Theatre, and/or the Somerville Theatre. Keep film alive, y’all.