As part of the ongoing COVID-19 crisis, the nation was rocked on April 1st by a rent strike as a near third of American renters did not deliver their expected rent. Whether impromptu or planned, an action of this scale, for this generation, is unprecedented — but it’s far from the first of its kind. In Boston, a city heralded for its revolutionary origins, renters’ movements have had their own largely unacknowledged history.

The most notable local instance of a rent strike was, undoubtedly, the 1968 strike at the Columbia Point housing projects in South Boston. As documented by the Jacobin People’s History Podcast, the rent strike originated in the Tenant Association Council, formed out of eight majority-minority public housing projects that had been constructed in Boston the previous decade. (As PHP notes, the other 17 projects were made up of 99% white residents.) The issues faced by tenants were numerous, with vicious rats and chronically unreliable heat being among the chief grievances. Even the election of Mayor Kevin White in 1968 seemingly did nothing in the way of material change for minority BHA tenants. One of White’s slogans was “When landlords raise rents, Mayor White raises hell”; however, the Black votership which had supported White’s candidacy initially still languished in Columbia Point and other projects.

Once tenants were organized, their action was swift and decisive. Columbia Point tenants initiated a lawsuit against the BHA in April 1968, with six thousand residents listed as plaintiffs. Then, the first strike came from 20 families at Columbia Point who refused to pay rent indefinitely until their grievances were addressed by BHA. While still able to pay, the residents held their funds in an escrow account until necessary material repairs were made. Though some repairs were made after the strike was organized, Columbia Point tenants would not see the tide turn from the establishment for years. In the book A Decent Place to Live: From Columbia Point to Harbor Point, Jane Roessner documents a sardonic protest by Columbia Point tenants at a BHA board meeting in December 1969:

“The tenants came bearing gifts… on a long table, in front of [the five BHA board members], they placed jars of holiday goodies. Dangling from green branches amidst the sparkling silver tinsel on the Christmas tree were half a dozen tiny dead mice. Carefully stored in the clear glass preserve jars were scores of dead cockroaches and a handful of squirming live black bugs.”

These novel and inventive forms of protest only did so much for Columbia Point’s case amidst the surrounding turmoil of Boston at that time. The 1970s and 1980s would see Columbia Point fall further into disrepair due to neglect from the City until its ultimate demolition in the late 1980s.

By 1970, rent control had been attained in Massachusetts cities with populations over 50,000. These measures came from tenant power across the state; as urban planner Peter Dreier notes: “The Massachusetts tenants’ movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s was a spillover of the student movement, the civil rights movements, and resistance to urban renewal… activists built tenant organizations in private and FHA-subsidized housing and helped enact rent control in Boston, Cambridge, Lynn, and Somerville in the early 1970s.”

This instance of leveraging power brought on roughly 25 years of political battle between renters, landlords, and lobbyists, with the latter two camps taking on forceful strategy to de-enact rent control. The controversial Small Property Owners Association (SPOA) was formed in 1987 with the aim of tackling rent control in Cambridge. By the mid-90s, the SPOA had grown its presence sufficiently to introduce a referendum question on the 1994 ballot to remove rent control statewide. As we know, the referendum passed, and the status quo that’s now in place began.

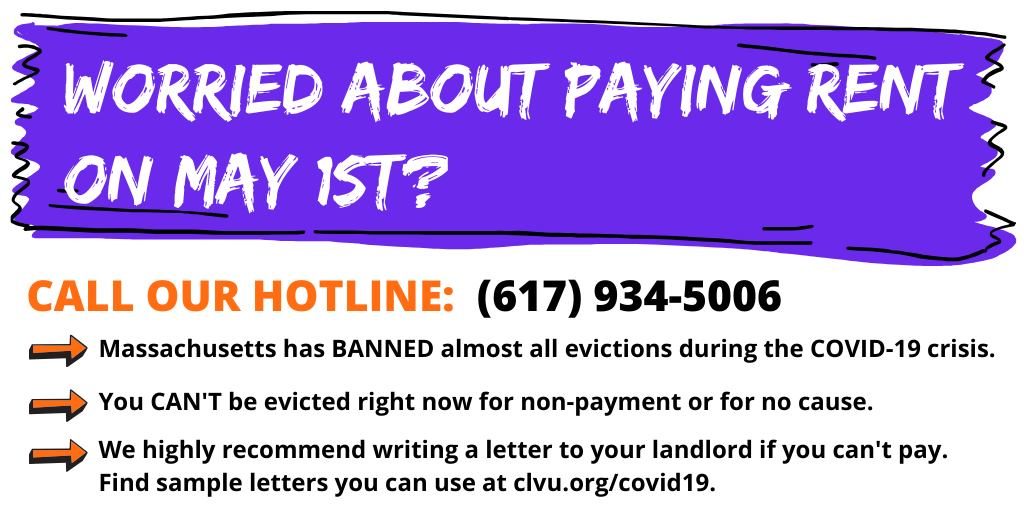

Low-income Bostonians felt the impacts immediately, and in due time responded with organizing again. The Boston Tenant Coalition was formed in the immediate wake of the 1994 referendum, bringing together public housing residents and market-rate unit tenants all together. City Life/Vida Urbana, a member of BTC, has been on the front lines of tenants’ rights battles in Boston for the past two decades.

But one affinity group of tenants took a more radical approach. Formed in the early 2000s, the Boston Angry Tenants’ Union was just that — a collective of renters who were fed up, not just with the political status quo, but with the immediacy of rising rents for increasingly shoddy units. In their newsletter, aptly titled “The Angry Tenant”, collective members decried current conditions of citywide units, identified the “Scumbag Landlord of the Month”, and provided health and safety information around dealing with bedbugs. A message from their 2003 issue haunts the reader today:

“From Mission Hill to Southy, Chinatown to Lower Allston, you can see gentrification at work in neighborhoods all over Boston. The rich move in, and we get pushed out. Does this mean that we are powerless in stopping this urban trend? Hell no!”

Tenants of subsidized housing, too, have mobilized amidst federal insecurity related to the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The organization Mass Alliance of HUD Tenants (MAHT) has been active since 1989, based in Jamaica Plain. MAHT has been instrumental in direct actions affecting not only Boston, but the whole nation — from its offices is coordinated the National Alliance of HUD Tenants, the only nationwide tenants’ union. Among their “thirty years of victories” are: securing a rent freeze for the 967-unit Georgetown complex in Hyde Park, leading direct actions through the streets of Boston to campaign for increased HUD funding, and helping secure $2.8B in stimulus funding for HUD in 2009.

One particular victory came from Tenants Against Mismanagement, a group of tenants of the Franklin Park Houses in Roxbury. In the late 80s, conditions were dire, with tenants complaining of “falling ceilings, missing security locks, exposed wiring, rats, mice, and roaches, uneven heat and hot water” as well as vacant apartments being used for drug dealing. Tenants Against Mismanagement faced potential for retaliation not only from the property managers, but also from the syndicates who were operating the impromptu trap houses in the vacant apartments. However, the group successfully sued HUD in September 1988, with the result being marked improvements from the property managers in keeping the development better maintained.

As we move through the COVID-19 crisis, the clarion call for renters’ movements is out and blaring. The beginnings of modern Boston, after all, began with the demolition of the once-thriving low-income neighborhood of the West End — an act for which a later BRA official apologized in its entirety. (Jerry Rappoport, the chief developer behind the West End redevelopment, is still alive.) One duty for tenants’ activists now, in addition to social media campaigning and boots on the ground, may just be boning up on this history. The rallying cry of “Another Boston is possible” may yet spark a revolution — whether by leafleting or by lobbying.

HASSAN GHANNY is a writer and performer based in Jamaica Plain. He can be found on Instagram @diaspora.gothic