In conversations about shoegaze in its prime, few bands are more overlooked than Boston’s Drop Nineteens. Though one of the first stateside bands to gain momentum with the then primarily British movement, substantial lineup turnover led to a stylistic about face in the middle of their relatively short career. After more lineup changes and a near-miss pursuit of a major label deal, the band unceremoniously disintegrated. Granted, they’ve ranked on certain best-of-the-genre lists and even still enjoy occasional college radio airplay, but for the ensuing two decades their story remained largely untold. As such, Drop Nineteens detectivism was among my first priorities upon arrival in Boston in 2017.

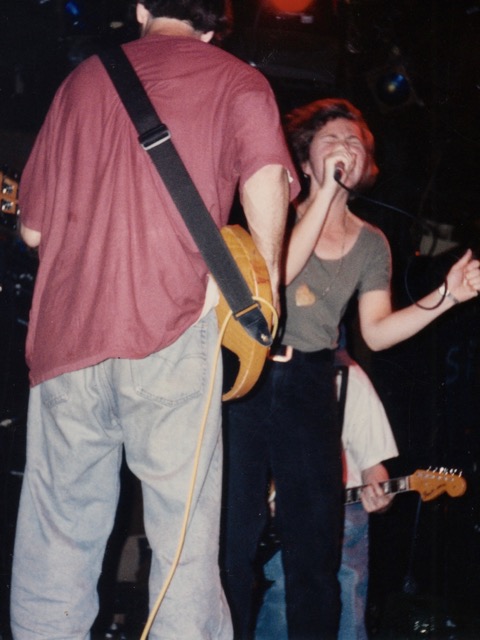

With fall approaching, the trail of clues led me to phase-two drummer Pete Koeplin, who was playing at at Midway Café in Jamaica Plain. Once inside the Midway, we met and I was soon introduced to founding bassist Steve Zimmerman and Koeplin’s cousin Justin Crosby, phase-two lead guitarist. At a corner table, we discussed the Drop Nineteens experience at length before Koeplin took the stage with The Chris Brokaw Rock Band. Founding drummer Chris Roof later filled in some of the gaps online and an article eventually went up which, though informative, could have gone further. Now this is upgraded with the inclusion of first-phase singer and guitarist Paula Kelley’s perspective, unseen band photos (also courtesy of Kelley), and an interactive, annotated map of Drop Nineteens’ Boston.

And so, with all of that out of the way, Boston Hassle presents the revised and expanded Drop Nineteens story as recombined from the collective memory of five alumni.

FORMATION

Formed in 1990 as In April Rain, Drop Nineteens coalesced under the leadership of Boston University student Greg Ackell. Even though just starting out at college, Ackell had conditioned himself an A student of new wave. “He was the person who came from boarding school, had played in bands, had done covers, really knew New Order, the Smiths, the Cure, had some vision about songs that he wanted to write that were his own originals, and could lead the thing at that young age, and was able to talk to the label people and get us into where we did”, reflected Zimmerman.

Roof recalled, “I played in a couple of bands with Greg when we were in high school at Northfield Mount Hermon School. I don’t think either of us realized we were both going to BU, but once we bumped into each other we talked about putting another band together, and we ultimately did.” Lead guitarist Motohiro Yasue completed the first incarnation of In April Rain’s lineup, while fellow BU student Paula Kelley initially appeared as primarily a guest, adding the vocal counterbalance that became the band’s signature.

Like Ackell she had an affinity for top 40 radio, but she also came with some prior experience in Boston’s underground music scene. On this formative time, Kelley said, ‘I lived in a house with a band-infested basement for a while [but] this was with my pre-Drop Nineteens band crew. I don’t remember which of my bands practiced in which basements.

Greg and I were hanging out in his dorm Freshman year. He whipped out his guitar and began playing…a Cure song, I think? When he was done I took the guitar from him and… I don’t remember what I played but I know I was trying to one-up him. I guess it worked or at least annoyed him enough to ask me to be in his band”.

BU and its surroundings provided convenient locations for the fledgling band to develop its sound, with Roof reflecting on them “first rehearsing in my dormitory’s basement music room, then the basement of a frat house in Allston.” Kelly added, “we lived on West Campus. I was in Rich Hall and Greg, Steve and Chris were in Clafflin, I think. Could have been the other of the three. They were pretty much all the same.”

Without a sense of urgency to start playing out, the band’s spent their early days experimenting with their sound. From this came a mix of atmospheric guitar layers and co-ed harmonies exemplified by predecessors My Bloody Valentine and Slowdive with lead guitar hooks reminiscent of classic 80’s dance-pop. “Somebody would come in with a riff, then we’d work it for hours/days/weeks until it began to turn into an actual song,” explained Roof. “We loved to get music down on tape, but it was primarily to get the word out. Before our two Drop Nineteens demos we did record one as In April Rain…I still have a copy of the tape somewhere; they were completely different songs.”

BECOMING DROP NINETEENS

In April Rain soon changed their name to what they would become known as and recorded what would prove to be a breakthrough in their career: the Mayfield demo. “I remember Mayfield really well; that was the song that caught us a lot of attention”, said Kelley. British publications like New Musical Express were impressed, and the buzz also helped Drop Nineteens finally get a show, which strangely was out of state. Roof recollected, “I believe [the first gig] was at UNH. Their radio station had picked up a copy of one of our demos and there seemed to be a bunch of interest there. The dark, live pictures that ended up [inside of the CD insert for] Delaware were taken at that show by my friend Turlach [MacDonough].”

Before long, Drop Nineteens were ready to record again. Zimmerman explained, “with the momentum we decided it was great to get in for the Summer Session, we called it, to do four quick songs. We went into the room with the intention of writing the EP as quickly as possible, and we felt like we had solid enough ideas to rent the equipment, and then like sort of isolate ourselves, and lay down the basics of what we had come out with, and then finish them up and get it out. So the Summer Session, which had what’s really called ‘Damom’, not Damon, ‘Song For JJ’, ‘Soapland’, and ‘Back in Our Old Bed’… it’s not part of Mayfield [as has long been miscannonized by fans]. There was actually a continuation, to try to maintain interest in the press. Show that we’re still writing, creative, and evolving, ‘cause that sound was even more washed out, even less immediate than the Mayfield demos.”

In addition to the shift in sonic gravity level, the Summer Session saw a temporary vacancy open in the band’s functional lineup. “I’m pretty sure it was because I was on tour with my other band…and the band I was in that conflicted with the Summer Session was unfortunately named Crab Daddy”, explained Kelley. This role would land with a mononymous Hannah. Roof further clarified, “Paula never was formally in the band when we recorded the [In April Rain and Mayfield] demo[s]…but once we started talking with record companies she formally joined us…I think Hannah knew Greg from someplace but am not sure.”

INCREASING ATTENTION

Over the approximately three months following the Summer Session, Drop Nineteens became increasingly effective at attracting industry attention. Roof continued, “the talk with record companies really picked up after we played our own show as a part of the CMJ festival in what was literally the meat packing district back then in NYC. I had to do sound and play the drums. I’m sure it sounded interesting, but it was a pure and raw show, which many of them were.” “A lot of labels were interested in us. Mostly British indies” recalled Kelley.

According to Zimmerman, “Cherry Red was the very, very first label to even offer, to put something on the table and say we’d like to do an album. Theirs was a tiny little deal, but Cherry Red was the first one to really sort of believe in us. We didn’t go with them, but there was quite a number of months where we were in talks with them, but then the other conversations started with other labels, and Caroline was a great fit for us.”

In the early ‘90s, Caroline had built its reputation as a seal of quality for the exploding alternative rock scene, boasting releases by leading acts like Smashing Pumpkins, Primus, and John Spencer Blues Explosion. Eventual band member Koeplin reminisced, “when you were going to like Tape World and looking for cassettes and records Caroline, you’d go and you look at Caroline records, [and say] ok I’ll give that a shot.” A sub-brand of Virgin, Caroline was, as put by later addition Crosby, “a packaging deal essentially. It was an image deal to test bands out for viability.”

On catching Caroline’s attention, Zimmerman remembered, “when we played with Chapterhouse they were there for the last few minutes, and it was our cover [of Madonna’s] ‘Angel’ that they saw. That’s all they saw, but, sometimes things go really well and that song that night sounded good. We were very manic. Greg was bleeding from the strumming from the show. So it was a real scene, bumping into everyone, but all of the starts and stops, and the wah that Moto was doing and whatnot. Everything was flawless, for that few minutes that Virgin happened to show up. So [it] made an impression, and so they contacted us more after. It didn’t become a frenzy, but it was enough for them to say, ok, we’ve heard about this, we showed up in time, we caught a little bit, and it started the conversation.”

Kelley added, “It really was a fantastic night. Most gigs that long ago are a blur, but I do remember that one well… I remember talking to the Caroline people after the show and just… it all happened so fast. It seemed surprising that we ended up on an American label; it was all but a foregone conclusion that we’d end up on a UK one. Something just clicked with Caroline, though. Maybe I just remember them being the people who got me the drunkest after the show.”

Signing to Caroline, the band had a few potential routes to choose from for their debut. After all, there was already an album’s worth of quality songs on the promo-only demos that could have easily been redone in hi-fi, but creative complacency was never part of the equation for the now-quintet. As such, a complete refresh of material became the preferred option. As Roof viewed it, “that was really our point – In April Rain was one incarnation, then the two Drop Nineteens demos were two more unique evolutions of the band.”

Zimmerman elaborated on the scenario, “there was so much backlash in the press about shoegaze and the scene that celebrates itself at that time, and because our interests were growing, we deliberately had a meeting, sat down and said how do we all feel about scrapping everything that we’ve made, which we know was a lot of to get to this point, but now that we do have a developmental deal, we are going to make an album. Write another all new album, and the way that [the Summer Session] was so fast to just crank out, those four songs and put them down, we had a lot of confidence that, sure, we’ll make an album. And so we set out to write songs of Delaware, wanting them to be more immediate, a little bit more of our own sound, ‘cause the [Summer Session] was even more Slowdive than maybe Drop Nineteens.”

To record their debut full-length, Delaware, the band entered Downtown Recorders at the South End’s historic Cyclorama building while still juggling school commitments. “A little bit hinged on our college schedule, so we were fortunate enough that we had some support from families to be in college, and we knew that if we weren’t in college, we wouldn’t have that same support. So we did classes and wrote, and then when were touring and recording, that that was part of the record company’s momentum, or contract let’s say”, explained Zimmerman. “So we sort of planned it so that it could be one or the other, cause we were too young to really…we didn’t wanna’ get jobs yet and we were too young to support.”

Featuring eccentricities like “Ease It Halen”, whose lyrics were constructed from Van Halen song titles, the eight minute soundscape-sandwiched-soliloquy “Kick The Tragedy”, stark acoustic numbers like “Baby Wonder’s Gone” and “My Aquarium”, a winning cover of Madonna’s “Angel”, and lead single “Winona”, which gained some traction on MTV’s 120 Minutes program, Delaware was a sonic grab bag housed behind a mysterious barber shop scene. However, like so many discs of artistic merit, Delaware sold better overseas.

It also didn’t do much to improve the band’s standing within the Boston scene. Kelley explained to Excellent Online in 2002, “Because we circumvented the system of playing around at local clubs before “making it” we were rather resented by bands who were doing that.” In fact, Drop Nineteens’ local live debut, at TT The Bear’s Place in Cambridge, didn’t even occur until after Delaware was recorded. Speaking to the Hassle in 2018, Kelley elaborated, “I remember that being a trainwreck. It was our first show in our hometown since we’d had a buzz built up around us, and all the local bands who’d been playing around town for years were so skeptical of us. Like they went to see us because they wanted us to suck. And we did.”

Outside of Boston, however, Drop Nineteens were taken more seriously, with strong appeal to followers of the big four S’s (Simple Machines, Slumberland, Spin Art, Sub Pop). Fittingly, they were invited to play Sub Pop’s now legendary Vermonstress festival in Burlingtion, VT that year alongside esteemed contemporaries such as Velocity Girl and Beat Happening. Kelly recalled, “Vermonstress…totally flipped that shit script. We were awesome, the people were awesome, the festival was awesome…man, what a good time that was. The vibe was different there because it was out of Boston. Boston can be tough. Tough crowds. Or at least that’s how it used to be. Now it could be a totally different experience for local bands.” Roof also fondly remembered the festival, saying, “[though I] do recall being intimidated to play at Vermonstress…it did really pump us up, and we played one of the most raw and in your face shows I remember that night.”

For Drop Nineteens, the Vermonstress experience stood somewhere between playing packed crowds in New York City and nearly vacant halls in Ohio during the Delaware era, but the highs and lows would become much more pronounced after another visit to the studio.

“The record company said it would be good to have more music out before touring. We also wanted to show how much our sound had evolved at that time,” commented Roof on the Your Aquarium EP, which contained a souped up version of the Delaware track and the group’s take on Barry Manilow’s smash “Mandy”. For Kelley, this endeavor was a highlight of her time with the band. “I love that EP. Making the video for My Aquarium was a great time. Actually, making the Winona video was really enjoyable as well. If they were doing one of those VH-1 “Behind the Music”s on us, that would be the time when they’d say, ‘The Drop Nineteens were riding high…’ to preface some shitty thing that happened. But yeah, despite our differences, we could really scare up a good time when we needed to”, reflected Kelley.

With the short new disc ready, Drop Nineteens headed to Europe. As a group, life on the road was rocky and being so far from their home continent seemed to aggravate mounting tensions. Roof explained, “we did band things together, and a couple of social things, but not many. Greg and Steve were tight for a bit. On the road Greg and Steve shared rooms and Moto and I did.” However, for as much as Kelley enjoyed the traveling and performing aspects of touring, she found this band’s European tour to be exasperating, and before long she had to make a choice. She shared, “the only people I knew were the guys in the band and I felt a bit of a fifth wheel. I especially wasn’t into being the only girl in the entourage. I was so young and didn’t have the hardened exoskeleton I have now. It was tough. The early 90s were different. There was no internet, and mobile phones had barely become accessible. When I was alone, I was ALONE. And I don’t mind being alone, that in itself isn’t the problem. Being alone in “your” group of people is a whole different feeling.”

CHANGING CAST OF CHARACTERS

With the prospect of a US trek to follow, Kelley announced she would leave the band at the end of the tour. “We took the ferry back to England [at the end of the 1992 European tour] and I stayed in London after that. They asked me pretty emphatically to do the next US tour with them- it started right when we got back and…I was like ‘No fucking way, no, nope.’ It wasn’t that I wanted to screw them over. I was just so done. My body and mind couldn’t have done it even if I’d wanted to…I got jobs waiting tables and got fired from them. In fact, I got fired from a job waiting tables right before the Drop Nineteens’ CMJ showcase. Why the hell did I keep waiting tables? Maybe because I love humiliation. Or hate dignity”, reflected Kelley. “So I lived in London for a couple years trying to get Hot Rod off the ground…On tour with the Drop Nineteens I did a lot of sitting in the backs of vans writing [Hot Rod] songs in my head. I can remember the exact scene when I came up with the bass line for “Tough.” Why that one? Not even one of my best. Brains are weird.”

Kelley’s departure initiated a radical transformation in the group, as almost immediately Roof would also make his exit. To fill the void, Megan Gilbert was brought in as Kelley’s successor on vocals and guitar, and Koeplin replaced Roof on drums. Koeplin’s memory of his onboarding remained quite vivid over time. He explained, “I actually met Greg through a friend of mine, Phil Maestrelis, who was a skateboard buddy of mine in high school. He’s also mentioned in “Kick the Tragedy” when it’s like, ‘fucking Phil is off…’. That’s my friend, Phil Maesrtelis…my late friend. He died in ’95, but Greg came and saw me play with my band Flipside back in high school, in my basement. He was visiting Phil, and [they] came into my basement, and Greg had, you know, Rayban glasses on or something, and watched me play for literally like, I don’t know, a minute; 30 seconds, and then left. And then I got a call a year later from Phil saying ‘dude, uh Greg’s looking for a drummer. I don’t know, opportunity might be knocking.’”

For Koeplin the prospect of hitting the road with a professional band seemed more enticing than hitting the books at UMass Amherst and worth taking a chance on. He continued, “Greg called me… he said ‘we’re gonna’ be recording a new record. We’re gonna’ be doin’…a national or international tour.’ It was something, and ‘so why don’t you go to the record store and find Delaware and the Your Aquarium EP, and listen to ‘em and come to Boston in a week and audition?’ And I was like, ‘well ok then’. So I went and I found the records and I listened to ‘em and I went in and that’s where I met Steve, Greg, and Megan? Was it? Cause I never actually met Paula Kelley. I still haven’t met her to this day. I don’t know if it was Megan or just [Steve], and Greg, and myself, and we just ran through a bunch of stuff…and maybe Moto might have been there. I ended up doing two shows with Moto, but I got that call like a week later saying we want you to join the band. We’re gonna’ be opening for Smashing Pumpkins in two weeks, and for me it was like the dream call, like are you kidding me? ‘Mom and dad, I think I’m gonna’ leave school to play in this band. I think its gonna’ be something serious.’ And that’s exactly what happened. Two weeks later, we were driving down [to Atlanta] in the blizzard of 1993 to play with Smashing Pumpkins.”

Yasue still held down lead guitar duties next to the two new members for the time being, but he too would soon leave.” Though she had already moved onto leading Hot Rod at this point, Kelley suggested, “I don’t know specifics but general sentiment in the band wasn’t great by the end of the first European tour. I can’t imagine that having nothing to do with Moto and Chris’s leaving.” While his exact cause for leaving is unclear, Yasue did occasionally face roadblocks on tour that may have been discouraging. Roof mentioned, “the only time we played [as] a four-piece was when Moto wasn’t allowed to cross the US-Canada border so we put him on a bus to Detroit, and we played Montreal and Toronto without him.” Kelley remembered this as well. “That was, well, not so funny at the time, but pretty hilarious now. I was freaked out because I had to cover his guitar parts…which I did…pretty terribly in Montreal. I had no advance warning there, but it went better in Toronto. And then imagining Moto hanging out in some hotel room in Detroit, smoking cigarettes and drinking beer, looking cool as fuck like he always did, while we were in Canada sucking…good stuff.”

Whether that had anything to do with his decision to exit the band is conjecture, but in any case, his time with Drop Nineteens ended without any shortage of adventure. Zimmerman described the trip as “that storm that that movie [The Perfect Storm] is based on, where the whole eastern seaboard just got pummeled. So even down in Atlanta, I remember being in Atlanta and nobody knew what to do.” Koeplin added, “it was a ghost town. Yeah, we heard on the radio, ‘The Smashing Pumpkins show has been cancelled tonight and we don’t know where Drop Nineteens are’, and we were like an hour outside of Atlanta and going like ‘we’re there, we’re coming! We’re right here!’ It happened though. It was the next night, right? They just put it off for a night and we stayed like two nights in Atlanta.”

Upon returning from their blizzard journey, Yasue parted ways with Drop Nineteens and the new incarnation of the band was about to leap into a new writing cycle with a new lead guitarist. As Koeplin remembers it, “when I first joined, it was learning Delaware and Your Aquarium, but it was immediately like, we got a practice space, which was underneath Jillian’s on Lansdowne street, and it was the four of us. I mean after Moto; after they told me Moto was gone I was like, ‘well my cousin Justin can play guitar.’”

WRITING THE FOLLOW UP

Crosby turned up about a month after the Smashing Pumpkins gig, somewhat surprised after having done his due diligence with their back catalog. On his initial experience, Crosby explains, “I was under the impression that [shoegaze was] what we were going for, so I was surprised when we started writing so different, but my entrance in was kind of right into the writing phase for National Coma, so cognitively it seemed like it didn’t make sense to me, but I mean it was just sort of adaptive to [Ackell]. Ironically, I listen to Delaware a lot and I was quite a fan of that album before starting the writing process.”

In Zimmerman and Koeplin’s view, this updated lineup essentially amounted to a “whole new band”, which was reflected in their drastically changed sound. Whereas Delaware’s writing was inspired by the likes of Slowdive and Sonic Youth, the band took a more modular approach to the writing of National Coma. Koeplin elaborates: “[We] had a practice space and Greg [would come] in with a part, and he would say, he was like ‘I got this’, and he would play something, and we would record onto a boombox. Greg would come in with a part, then Steve would know something too, and I would try a beat to it, and then Justin would try something. And we’d record that part, and then it would be like ok, here’s the next part, and we would do things in pieces, to the point where, by the time we got to Syntex Studios to record, Greg was on the box going, ‘let’s try this part’, and fast forward, and he would go ‘and this part’, and we’d put them together and make a song. Which is, to me, was kind of like, maybe why National Coma sounded [exactly like that].”

“Cuban” was the first tune worked out for National Coma, which garnered a mixed reaction from Caroline’s office and Koeplin’s parents alike. He joked that “after that BAM BAM, you know I think that no one knew quite what to do with that.” Zimmerman, however, maintained that the label saw promise in the group’s new direction. “Caroline liked that one. They were like woah. So they were very excited to hear what was next, cause it had some of the classic elements of Greg and Megan’s vocals, the male/female vocals. It didn’t sound like shoegaze anymore, but it had a softness to it and it sounded like it could be an evolution and that other songs that were coming behind this, which the other songs were nothing like it.”

Crosby added, “My favorite tracks, ironically, are [UK b-side/Japan bonus track] Sea Rock, which is pretty much all [Zimmerman]…and then Skull actually, [which] was the one that really linked Delaware and National Coma. And then Cuban I loved. There were some pieces that I really really loved for sure…I think I had learned about odd time signatures. I was like, yo guys [hums riff from “7/8”].” Koeplin specified, “ [7/8]was Justin and I specifically’s donation to [the new repertoire], I remember we were riffing on that and we just called it 7/8.”

The label’s puzzlement grew as more songs were submitted. “They were really excited about it, and then they got the rest of the album. After a while our A&R guy said, ‘I think it actually might be genius’, but they had a real hard time figuring how to market this. What do we do with this?” reflected Zimmerman. “It was always like, well what’s the single? And the closest we could even get to an answer was ‘The Dead’. [Note: “Limp” was ultimately issued as the single from National Coma.] We just took a left turn. We said no to some producers. We looked at some producers. They actually asked Jimmy Destri from Blondie, the keyboardist. We met with him, sat with him, and were like, nah we’re not sure, we’re not sure if we’re really gonna’ comingle so well. And we really wanted J. Mascis, but he was busy. He had heard about it, he did have interest, but he couldn’t, the time, the schedule wouldn’t work, so we just did it ourselves”.

The final product that was National Coma reflected the breadth of the revamped band’s collective personality but didn’t exactly captivate Delaware’s audience anew. As Zimmerman posited, “the demos did great, Delaware did great, and so when you always do great you don’t think that people who want to listen to what you do aren’t gonna’ accept the next thing, even if it’s a turn. And when you’re that age, also, you don’t necessarily understand sound. What it was that might be your trademark, your own brand, your trademark and your sound, and think that if you completely crumble it and make a different thing what that might mean to the audience or to the company who has decided that they’re gonna’ make an album with you based on a certain sound. It’s a pretty interesting thing.”

As National Coma’s launch unveiled the revamped Drop Nineteens new direction, SpeedDangerDeath by Kelley’s successor band Hot Rod arrived in stores nearly simultaneously. Kelley said, “I wish I could say I didn’t [feel a sense of competition with Drop Nineteens], but yeah, I kind of did. Being part of the shoegaze scene, living in London in the early nineties…that changed me. Bands were so competitive. I lived with guys in another group from that scene. For them it was rote to go pick up Melody Maker and NME right when they came out and pore over the charts and obsess over breakfast. And then we’d see all the bands every night out drinking and at gigs and it was like this fucked up family comprised of only siblings.”

NATIONAL COMA TOUR

Now having a pair of mismatched sounding records in stores and Hot Rod as a challenger, Drop Nineteens hit the road with in support of National Coma with a setlist Koeplin likened to shuffling the deck. “ I don’t know if I could go back and listen to that set now, what that must’ve sounded like… to go from ‘Winona’ to ‘7/8’,” opined Zimmerman. Much like the Delaware-era tours, show attendance sharply contrasted from show to show. Koeplin recalls, “when we were playing in the UK… until we played the Reading Festival, we were on that stage and playing the songs. By that time, I remember people jumping around and dancing, but there were a lot of club shows where there was like 20 feet of nobody, and a crowd of people watching doing absolutely nothing but just watching. And I didn’t know if it was because it was…such a divergent thing. Like, they couldn’t put A and B together and figure out like how is this gonna’ work together. It was still like trying to figure it out, you know.”

Also like the prior version of the band’s time on the road, moments joking around punctuated the season’s rising tensions. Koeplin, for example, relayed a time when, “we wrote Radiohead sucks on the wall at one point, at one of the clubs,” with Crosby adding, “[that] the irony is, I remember we were at the Reading Festival and we were all knocking Radiohead, like we were knocking Creep….and here they are, one of my favorite bands, like over time, oh my God they evolved into this behemoth of something authentic. And there, that just shows you the maturity level I was at for sure.” However, even incidents like this though proved unable to preserve the National Coma-era Drop Nineteens as they were.

THIRD TIME’S (NOT) A CHARM

Looking back on that incarnation’s unraveling, Crosby stated, “it just kind of very quickly ramped up to that, and I remember there was always some tension there, but it was very abrupt.” Koeplin elaborated that “no one got fired, but at the immediate aftermath of the National Coma tour, which ended like Christmas, December of [1993], Greg’s like, ‘hey, I’m flying everybody home’, and we were like thank God. So we all went home. I got a call from Greg in like January, and it said that, ‘I don’t think that Steve or Megan are gonna’ come back. I’m not sure about Justin,’ and I think he asked me do you wanna’ like, who do you know that would wanna’ play? Like, what do you wanna’ do? And, I was like, well, you know, without any hint of I’m so sorry that’s happening, which is what it would be now, I was like, well, I know my friend Craig Rich plays bass, and…there was a couple formations of the band that came, and we demoed a few things.”

The post-National Coma demos, pitched to London/Polygram, nearly earned the band a new major label deal but, in Koeplin’s view, “the wheels were falling off by then.” Some creative fire remained in their stove, but as Crosby put it, “it felt like it was musical chairs, where it was just so like rapid where it was like pace kept picking, and then boom, suddenly [Steve’s] gone, Megan’s gone and it was just…and you know, I’m in because they were replacing, it was like, it was kind of like The Cure [with] the ever-rotating cast of characters, which is unfortunate. It just seems like there was nothing to latch onto that I could understand from an authentic perspective.”

Crosby also attributes a lack of outside involvement to the ultimate halt Drop Nineteens met, stating, “it wasn’t one of those bands where you had your, say 40% of your gigs were DIY, where you were calling when you had like off time and setting up weird little tours around the state, like, and … I don’t know if that was unique to our situation, where bands, you know, where they’re insulated by a label. ‘Cause it’s interesting to see that I feel like that was another thing that would have helped glue everything together, if there was this ethic of just like keeping us playing and, you know, and gigging when we were in between albums. You know, like that’s sort of really is the heart and soul of what keeps a band alive when they’re not recording. I think the problem was we never had someone actively on the periphery keeping us glued together.”

Contemplating how the band might have been able to survive, Zimmerman added, “if there was a producer involved or a manager who’s very strong and just said there’s some differences, there’s some things going on here. I don’t know if you should still be Drop Nineteens, but I see something here, let’s take this and now go make another album. We’re gonna’ rebrand it maybe. We’re gonna’ do something else.”

FIDEL

Such a rebrand did eventually occur, with Ackel, Koeplin, and Rich briefly continuing as Fidel with keyboardist Chris Coates. Fidel recorded a full length album and played a few live dates, but their released catalog only ever comprised of their song “Randy Bean” appearing on the 1996 Wicked Deluxe complilation. Koeplin summarized, “we recorded [the album] at Fort Apache in Cambridge…we played Mama Kin’s before Mama Kin’s closed, and I, and I mean, I think Greg is a, God bless him man, he’s a creature of…when he’s into something, when he’s into the project and he’s interested in it he does it for all it’s worth, but the minute that it kind of like, maybe isn’t going to be worth it to a certain, or he doesn’t see it in the long haul, like that band just kind of fizzled out. We practiced, you know, we worked hard, but then like most bands, it just came to a point where we just didn’t practice anymore, and if no one’s gonna’ book a show, who’s gonna’ do what? You know, it’s bands just kinda’ come and go… if no one’s actively booking the band, and saying we’re practicing tomorrow, you know, how does a band survive?”

EPILOGUE

Before long, even Fidel ceased activity and, as the mid-‘90s progressed into the late 90s, the Drop Nineteens alumni all moved on with their lives. After Hot Rod, Kelley led Boy Wonder and eventually founded the Paula Kelly Orchestra before pursuing a television and film composition career in LA. Crosby too carved out a niche composing, with his work appearing in household name media ranging from Dexter to WWE. Roof recounts having, “played with a few friends’ bands for a while after [leaving Drop Nineteens] and [doing] sound for others as well, including briefly at Club Passim in Harvard Square.” Koeplin continued active involvement in the local music scene, playing with acts including Kahoots, Paul Tait, and Chris Brokaw. Gilbert resurfaced circa 2010 as part of New York duo La Marcha. Though his work with Drop Nineteens never saw the light of day, Rich eventually released a solo album, Pachanga, in 2005.

GHOSTS OF PAST AS FUTURE?

At some point in the 2000’s, between the dawn and dusk of All Tomorrow’s Parties, the nostalgia cycle made the shoegaze reunion scene a thriving one but Drop Nineteens have remained one of the few conspicuous absentees. Surprisingly, this isn’t for lack of effort. Kelly recollected a Summer 2001 occasion where “we met up in a gentrified dive bar in Boston (The Model- does that still exist?). I remember Greg talking to me about how “reunion” albums and tours were really big at the time and we ought to jump on it, etc. I thought it was odd that they even asked me, as the sentiment in the band was rather unfortunate at the time I left. The main reason I decided not to do it, though, was because I…was really busy and doing pretty well at the time.”

Zimmerman also reflected, “I remember talking about [making a new Drop Nineteens album]. Paula had momentum with things that she was doing, and we just couldn’t come to an agreement on it. And then that was it. I think we had one practice session, Greg and I, and then he called me the next day and said we’re not gonna’ do this. So we could have called Megan, we could have looked for other people, um, we hadn’t actually reformed the band or done anything yet, but it was just a thought, and that started with, well we know the sound of Greg and Paula’s voice together is what, is desirable, at least under that name of Drop Nineteens. And when that was already, when she was already saying I’m gonna’ pass on that and it wasn’t right for her, it just didn’t seem like there was a point.”

In truth, they may have been a bit too early for peak retro-shoegaze, but as the decade progressed, a few ghosts of their past began to appear. In 2005, Koeplin created pages for Drop Nineteens’ National Coma era formation and Fidel on the then cutting edge site myspace, and Zimmerman soon reciprocated with a dedicated Delaware-era page. These pages showcased rare audio and photos, and gave fans a practical way to connect with at least those two, but as defunct band, there wasn’t much to post on the Bulletin Board. That was, until Cherry Red had acquired the rights to have their mulligan with Drop Nineteens, whose catalog at that time was long since deleted.

“Every couple years, I shit you not, I get an email from a company that says we own your stuff now. We just wanted you to know that so its ok”, said Zimmerman. “I mean, its crazy, but its funny how that came full circle, and I wonder if the guy who even contacted me at the time had been there way back in the day, in the beginning. I never asked him that. I ended up landing on Cherry Red after all, for a time before UMG took it…It’s like a mortgage, it gets sold from company to company. It’s nuts”

Delaware received the deluxe treatment Cherry Red had earned a reputation for, including an original interview with Zimmerman and a resequenced Your Aquarium EP. This reissue, however, did not eventuate into a campaign including National Coma, which would change hands again before a run of the mill digital soft-relaunch. Zimmerman speculated, “I don’t know if they actually purchased National Coma or not…I think all that was [is] that Delaware’s the desirable one, let’s say. No dig on National Coma, but if they’re gonna repackage something, they felt like that one might be the one that might move a couple of units.”

In a similar sentiment, Crosby stated, “To me, Delaware is an album where it’s like, this is the band. This is them being themselves, and then, you know, National Coma was sort of a weird in-between phase, cause everyone was trying to feel each other out but then I think about cutting the demos afterwards, and…there wasn’t much authenticity by then…So I feel like Delaware is the album. Like [Zimmerman] said, Not only its the most saleable, it’s the album I listen to most. I like, I very rarely listen to National Coma.”

Unfortunately, the Cherry Red reissue was soon discontinued, barely overlapping with shoegaze’s ascent into the wider nostalgiasphere marked by My Bloody Valentine’s 2008 comeback. Fast forward to the late 2010’s and festival season lineup announcements are showing diminishing returns for college rock reunions acts. Of course, Drop Nineteens are a remaining stone unturned, but even after almost a quarter century the proposition still isn’t unanimous.

Koeplin seems to be the most enthusiastic. While noting that Ackell is “generally not too interested in rehashing the past”, he admits, “I’ll always ask for a reunion, and I will never get one, but it’s ok. I’ll keep asking. I think I asked Steve last week…[but]it’s gotta’ be all or nothing. I mean Greg’s gotta’ be involved if that’s gonna’ happen.” Zimmerman agreed, “Without the singer…It won’t sound good…if he’s done focusing on it it’s done.” For his part, Crosby isn’t so sure himself, initially joking, “my reunion question is you ever heard from [manager] Gordon [Biggins]”, then more plainly assessing, “I don’t know if [I’m] in. I think I’m too old for it.” Kelley’s stance hasn’t changed over time either, with her plainly putting it, “I don’t know why that would ever happen. Who would want that to happen?”

And so, as it stands, Boston’s Drop Nineteens remain strictly a phenomenon of the past, but at least their name is still an available MA vanity plate!

INTERACTIVE MAP

Now you can explore Drop Nineteens’ old stomping ground with this interactive map, containing about a dozen known locations that figure into their history. See what these places look like now and read what the alumni have to say about them. If you have trouble scrolling through the map captions, try a different browser.

Header photo by Stephanie Marando-Blanck

[This article is adapted from a piece initially published on Square Cotton Candy 11/15/17]

this was cool. thanks.

Much appreciated Andrew.

Hearing “Delaware” in 1992, the Drop Nineteens quickly became a favorite. Heard them live at Metro Chicago on the National Coma tour. (who has a recording of THAT?!?) “Kick the Tragedy” is among the most meaningful tunes of my life. Years went by, and via blogs, I found the “Mayfield” demos, and live Burlington 92 recordings. But overall, band details were scarce. I never stopped listing to them in my rotation and always was looking for more facts. Thank you for this amazingly informative article! Paula’s fantastic photos and the back story on “F**ing Phi, off on his board somewhere” … um, that’s just “orange trees in the backyard” level bliss

Thanks for this article – really good to have some of the blanks filled-in on the history of Drop Nineteens.

One extra thing that I’ve wondered about is: what is the story behind the Delaware album cover with the girl standing out the front of the barber shop with the pistol? Was that an existing photograph, or did the band take it themselves? Who was the girl, and was there some symbolism behind the photo? It’s an intriguing photo, so would love to know more about it.

The cover star was provided by a talent agency which I don’t beleive is credited on the inlay. The photographer though, Petrise Briel, is still active in the field and may have more substantial insight into the work itself.

Interesting article! Petrisse Briel is my Aunt. I knew Greg from NMH and referred her. She is still working and living in Marblehead but doing more sculpture than photography now. I do remember the girl was hired for the shoot- not someone they knew.

this is amazing. thanks.

Hello , in the past I promoted a gig for Drop Nineteens , It is still one of my favourite bands and I still don’t understand the world why they are not yet recognised . OK That’s mostly like that . I really want to buy , download or wathever the unreleased album ‘Mayfield ‘ can somebody help me with this ?

and you will see , in the future Drop Nineteens will be still standing while other bands like Smashing Pumpkins will fall down because they are not authentique . As an old bastard (61 ° ) and I promoted over more than 800 bands and I have seen the same with the german Krautrock band like NEU ;

@Alfons Noeyens

The pre-Delaware demos never got a commercial release but Mayfield combined with the Summer Session has been somewhat readily available for years, albeit unofficially. I’d recommend a quick Lycos search. It would’ve been great if they made it onto Cherry Red’s 2009 deluxe version of Delaware but that’d probably require q second disc and locating the original source tapes. It’s a small wonder no one’s gone through with a bootleg vinyl pressing of the demos by now.

Thanks for excellent article! I sure that Drop Nineteens were always more famous here in Europe than in US. I am an old grey fart but with good memory, Drop Nineteens were heavily played on Europe’s indie radios and gained lots of attention. Personally, Mayfield demos are my favourite No.1, Delaware very good, still, but I can not get into National Coma.

What a great article, thanks very much.

Winona was given considerable airplay in the UK and the music video featured weekly, for a time, on The Chart Show every Saturday morning which is where I first became of aware of them.

Its a shame that things didn’t pan out that well and that a reunion can’t gather any traction but I guess some things aren’t meant to be.